Daniela Vega in "A Fantastic Woman" Courtesy of Sony Pictures Classics

As celebrities descended upon the Beverly Hilton for the Golden Globes earlier this month, fans abroad in Santiago, Chile, gathered in crowded bars to watch the award ceremony on television. At moments, they broke into a level of cheering normally reserved for soccer matches—all for a bold new film featuring their country’s only out transgender actress.

Daniela Vega is a newcomer to the red carpet, but she’s hoping to make history in Hollywood this year: There’s talk that the 28-year-old Chilean could soon become the first transgender person to ever garner an Oscar nomination for acting, for her breakout role in A Fantastic Woman.

The film tells the story of a trans waitress and singer grappling with the sudden death of her lover in Santiago. It earned glowing reviews (“a feat of acting,” Variety wrote) and was nominated for the best foreign language award at the Golden Globes. Though it didn’t snag that prize, it is now shortlisted in the same category for the Academy Awards, and some critics think Vega has a shot at a best actress nomination too. (Nominations will be announced on Tuesday.)

It would be a rare feat: Hollywood heavyweights like Meryl Streep (The Post), Jessica Chastain (Molly’s Game), and Saoirse Ronan (Lady Bird) are also vying for the title, and few foreign-language films have ever scored in the Oscar’s acting categories. But Vega seems undaunted. When I met her in San Francisco this month, days after the Golden Globes, she was completely adorned in red—beret, dress, lipstick—at a circular table beneath grand chandeliers in the luxurious Fairmont hotel. Director Sebastián Lelio joined us for a conversation about the transgender movement in film.

Mother Jones: How does it feel, the possibility of making Oscar history?

Daniela Vega: I travel with the film wherever it takes me. I don’t like to feel anxious. Therefore, if that moment arrives, I could answer that question.

MJ: Where does the title of the film come from?

Sebastián Lelio: Well, “a fantastic woman” is a common saying in Spanish. Like, “You are a fantastic woman”— it’s normal, used on an everyday basis. What I like about the title is it’s kind of retro, from the ’70s, like An Unmarried Woman or A Woman Under the Influence, which are films that I love, and this film more or less belongs to that tradition. “Fantastic” means that which has extraordinary properties, and also that which is the product of fantasy. And the film is open enough to let you decide what “fantastic” means in the title.

MJ: How did you start working with Daniela?

SL: It happened naturally. I was looking for someone to help me get rid of my ignorance, and I just wanted to talk to a transgender woman and learn more and gather material to write the script. And Daniela generously accepted to be our consultant, and we became friends. Because of her, I realized that I wanted to make the film, that I was not going to make it without a transgender actress, and that she was the star.

MJ: Why do you think there aren’t more actors in Chile who are trans?

DV: There are no laws to protect trans people. It’s very hard to have a career without tools, and I did it without formal tools. Very few trans people are participating socially in Chile.

MJ: I can’t stop thinking about the scene in A Fantastic Woman where your character, Marina, is attacked by her late boyfriend’s family members, who wrap her face in tape and call her horrible names. In your own life, have you ever faced violence or discrimination?

DV: For being trans, for being a woman, for being Latina. I think everyone has experienced violence and discrimination.

SM: Other award-winning films—like Boys Don’t Cry and The Danish Girl—have used cisgender actors to play transgender roles. Why is it important to give transgender actors a shot at the part instead?

DV: It’s something natural that should have happened a long time ago.

SL: I guess what those films had against them was the time in which they were made. Now it’s too late for that. That’s my personal feeling. And I do believe that anyone can interpret any role. It’s not like a moral statement to say only transgender actors can play transgender roles. That would be like committing the same mistake. For me, it felt like an aesthetic aberration, to do this film without a transgender actress at the center, like an anachronism.

MJ: Last April, Chile’s Ministry of Education said schools could be punished if they didn’t allow trans kids to use bathrooms that corresponded with their gender identity. This was about one month after the Trump administration revoked those protections for trans kids in the United States. Do you think that timing was a coincidence, or were they at all related?

DV: We’re connected, the world is connected. What happens in one place can be replicated in another. And one can put pressure from different places in order to live freedom in another way. There’s an intention to improve the way things are being done [in Chile]. But there’s also a counterwave that attempts to forbid that. That’s where we are: fighting.

MJ: What has the response to the film been like in Chile, given some of its conservative tendencies?

SL: The film during the year has become more well known—it overflowed. So it wasn’t about the film anymore. It was about the subject, Daniela’s presence, and what that subject and presence were doing to society. And because of the film, the discussion of what’s possible and the legitimacy of minorities has grown. Like during the Golden Globes broadcast, there were people watching the show in the bars like it was soccer. And that’s something that rarely happens with something that is not soccer in Chile.

MJ: Daniela, how has your training as an opera singer influenced your career?

DV: I started singing when I was very young, and the music allowed me to stop listening to the sounds of other people who I didn’t want to listen to.

MJ: Who are your favorite actors?

DV: There’s a very interesting Spanish actress whose name is Bibiana Fernández. She worked in the ’80s and was one of the first trans actresses who arrived in cinema.

MJ: And what about your role models?

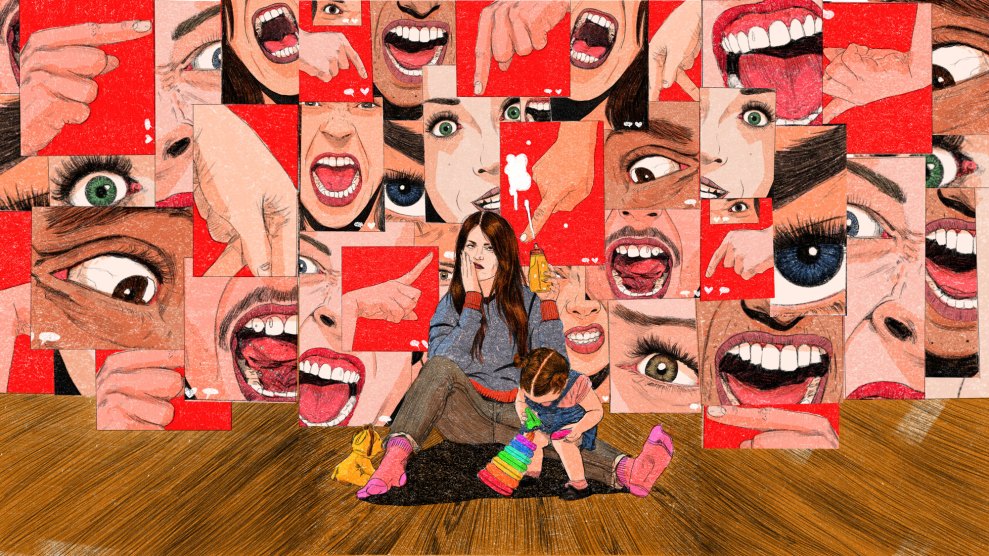

DV: The women in my family—my grandmothers and mother—and so many women in the history of humanity that have done things toward women’s freedom. All the women that have helped women to be able to vote, to have freedom around their bodies. Those that went to university for the first time. Those that started acting in theater—in many places, only men could act and sing. All the visionary women who used a torch to illuminate a dark space.