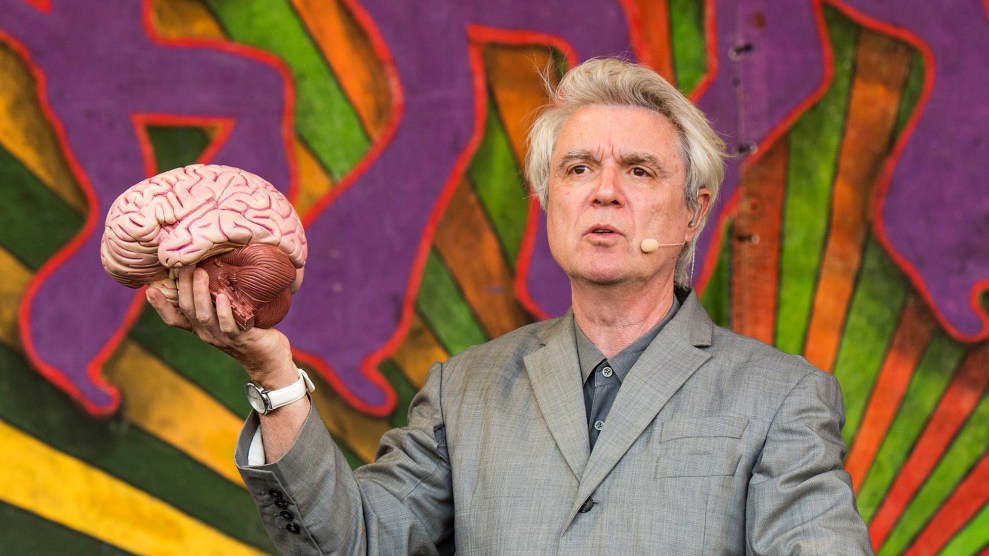

David Byrne performs at the New Orleans Jazz and Heritage Festival in April.Amy Harris/Invision/AP

Since the late-1970s, when David Byrne formed the iconic (and alas, now-defunct) Talking Heads, his career has been an endless stream of fascinating side projects, starting with his super-weird, super-cool Brian Eno collab, My Life in the Bush of Ghosts, and his scoring of choreographer Twyla Tharp’s The Catherine Wheel. He founded his own World Music label, Luaka Bop, and wrote half a dozen books, including the best-selling quasi-memoir How Music Works. His obsession with the National Color Guard Championships led to a documentary called Contemporary Color. Most recently, his American Utopia tour featured dancers and musicians untethered from the standard concert setup by means of wireless and wearable instruments—nary an amp nor drumset in sight.

In November, as the tour wrapped up, came the re-release of Byrne’s 1986 film, True Stories, which explores the inner lives and outer quirks of residents of a fictional Texas town and is based on stories from tabloid newspapers. Byrne once described True Stories as “like 60 Minutes on acid.” The timing of the film’s re-release was brilliant—but also coincidental, he admits: “I hadn’t looked at it in a while. And a lot of it does seem prescient and newly relevant. There’s a lot of stuff that seems oddly like, ‘Oh. I recognize this! It seemed like fiction in the movie, and now it’s fact.’” Byrne recently came by our New York City studio to tape this episode of the Mother Jones Podcast. Listen below, or read on for our edited version of the conversation.

Mother Jones: You were born in England. Does that give you an outsider perspective?

David Byrne: Probably a little bit. I grew up mainly in a suburb of Baltimore, but we were immigrants. My parents kept their diets. Their writing, and things they talked about—I was aware as a child that the culture, the food, the music of my schoolmates was not the only way the world could be. It gave me also an appreciation of some of the things Americans do. There’s a wealth of creativity. There’s a can-do spirit: “People may say I’m crazy, but I’m gonna do this.” Which is really wonderful to see—a feeling like, “I don’t care what you think about the fact that I drive this car or I live like this or I dress like this.”

David Byrne in his 1986 film, True Stories.

Criterion

MJ: What do you like about directing, as opposed to your other work?

DB: Making a film is very much a collaborative affair, but to some extent you’re playing God. It doesn’t get much better than that. You get to say what people say and what they do and if they live or die.

MJ: What was the attraction to tabloid stories?

DB: The tabloids—this was the Weekly World News—tended to have really amusing things about aliens or “Baby born with three hearts,” but it also had human interest stories. It was like a Buzzfeed phenomenon, where they would take an ordinary story and put a more exciting headline on it, and maybe rewrite it a little bit to highlight the drama. Like a lot of supermarket shoppers, I was drawn to some of those. And I thought, “These might be exaggerated, but my guess is that they’re based on real people. I’m gonna make those some of my characters. Let’s see if they can fit into the world that I imagine.”

MJ: You read about the Donald Trump-Enquirer scandal?

DB: Oh, the guy who did…what’s it called? Catch and burn?

MJ: Catch and kill.

DB: Yeah. I thought, “This policy has a name!” This was something they did over and over again. I’m really curious. Apparently, they have a whole trove of ’em on Trump. And now that [publisher David Pecker] has been called in [by Robert Mueller’s team], I’m thinking, is he going to open that trove? It’s going to get very juicy, I think.

MJ: We’ve heard through the grapevine that you are a Mother Jones fan. So a) Is that true? And b) Why do you think investigative independent journalism is important right now?

DB: Yeah, I’m a fan, especially of the investigative pieces Mother Jones has been doing for the last I don’t know how many years. And I was happy to point out to some friends who were talking about who wins the Pulitzers and who gets the journalism awards, “Look. It’s not just the big ones that are getting these kudos. It’s Mother Jones. Or it might be a newspaper in Tampa or wherever. They’re putting in the hours, breaking stories that sometimes the big papers are missing. It’s essential that honest, fact-checked journalism exists as a check on abuses that our elected representatives tend to get into. The press is essential for the operation of a democracy, because it keeps the government partially honest, at least.

MJ: One of our editors saw you during your recent tour and loved it. He said you implored everyone to vote, and took some veiled jabs at Trump.

DB: Actually, I’m completely nonpartisan from the stage. We’ve partnered with an organization called Head Count that registers people right there on the spot. And I urge people to vote in all the local elections. Because a lot of cities, counties, cantons, states, whatever, are making a lot of changes and adopting a lot of initiatives and doing things the federal government hasn’t done for, geez whiz, I don’t know how long. I’m not going to tell you what side to vote, but you just have to do this—or stop complaining.

MJ: Is “nonpartisan” secret code for “Vote Democrat?”

DB: Not exactly. My feeling is if you’re not excited about the national candidates, at least vote on all the local elections. It’ll make a huge difference. I made one little jab: I do a song from a musical I wrote about Imelda Marcos, the former first lady of the Philippines. She was married to dictator Ferdinand Marcos. And Paul Manafort did some work for him back in the day. And I said, “Well, there you go. It comes around, doesn’t it?”

MJ: Have you come across any successful resistance art?

DB: On tour, we ended the show with a song by Janelle Monáe that she did at the Women’s March, one of the most powerful and moving songs about social injustice I’d ever heard. I thought, “I can’t write anything better than that.”

MJ: That song is called “Hell You Talmbout,” and it lists the names of black people killed by police—or bigots, in the case of Emmet Till. Why did you adopt this particular song?

DB: It wasn’t wagging fingers—I mean, there’s anger there, obviously. But it was more about heartbreak, about the emotion of what this means and what this does to families, people, the individuals involved. It’s asking you to remember these lives. This didn’t have to happen. This was a person. I wrote to her and said, “What do you think about this older white guy doing this song?” I mean, my band is very diverse; it’s not just me. She was all for it.

MJ: Your tour is called American Utopia. Is that title ironic?

DB: Well, sort of. But sort of not. I like to think of it as being about the longing and the desire that people have for something better. I’m not proposing, well, here’s what utopia would be, or here’s how we should do things. I’m not going to lay out a program. I don’t even have one for myself!

MJ: Has performing gotten easier or harder for you over time?

DB: I don’t know if easy is the right word. It’s certainly gotten a lot more joyous. When I started, it was something I did out of a psychological necessity. I was very socially inept, and performing was a way to announce myself to the world or to communicate. And then I could retreat back into my shell. And now I’m a little more relaxed about that. Performing isn’t so much an act of desperation.

MJ: You’ve said you “probably” had Asperger’s Syndrome. Was stage fright a problem for you?

DB: This desperate need to say, “Here I am. I exist,” took precedence over any stage fright. I would just get out there. Even in high school, I could do really odd things in public on stage. And then when I got off the stage, suddenly I was really nervous about talking to anyone.

MJ: You still perform some Talking Heads songs. Any all-time favorites?

DB: That’s actually a tough question. Often I choose them because I think they’ll fit into the set; they’ll sound good given the arrangements we’re doing. I’m not necessarily choosing them because they’re my favorites.

MJ: Let’s flip the question: Are there any Talking Heads songs you never want to play again?

DB: There’s quite a few that I’ve never performed, ever. There was one called “Popsicle” or something. I thought, “It’s not one of your best efforts.”

MJ: Have you kept up with your old bandmates?

DB: I stay in touch with Jerry. The others not so much. Bands who stay together for a certain amount of time, it becomes like a family. You’re with those people all the time. If you’ve ever been on a road trip with your family, the smallest things start to annoy you, and you have to get past that: Stop doing that with your finger! Would you stop that? All those things. Which don’t mean anything.

Economics plays some part of it. As years go by, it becomes more apparent that the person who’s doing the majority of the songwriting gets the lion’s share of the publishing money, which is about half the income from songs—recordings, not live performance. That can hit a band pretty hard when one or maybe two members are getting much more income than the rest. There are various strategies of trying to address that. In our case, there was maybe no way to fix it permanently.

Byrne with fellow Talking Heads at the 2002 Rock and Roll Hall of Fame induction ceremony.

Nancy Kaszerman/ZUMAPRESS.com

MJ: That’s often hinted at in those behind-the-music stories we hear.

DB: Oh, yeah. I can imagine a lot of bands, they’re gonna say, “Oh, no. It’s not about money.” Yeah, it sure is about money! That really became something we had to deal with. As you’re implying, it was never approached directly. It was approached obliquely. The other thing is, sometimes musical interests really did take me to places that were not appropriate to execute with the band I was with.

MJ: What’s your next project, besides creating more music?

DB: For a few years I’ve been working on a immersive theater project based on neuroscience experiments. Who knows if it’ll ever come to pass.

MJ: Creative people like to talk about their muses, and I’ve wondered if that’s just something they say. It’s a bit of a cliché. Do you have a muse?

DB: I have friends. I wouldn’t say they were muses, but they become a sounding board. I run ideas by them and play ’em stuff. And I definitely listen to their feedback. That doesn’t make them a muse in the sense of, “Honey, stand over there while I paint this picture.”