The border wall between the USA and Mexico in Arizona.Getty Images

In the fall of 1993, Aaron Bobrow-Strain arrived in Tucson, Arizona, near the jagged ridge of the United States’ southern border. Dominating the news was debate over the North American Free Trade Agreement, which would be passed by the House that November. As Bobrow-Strain settled into his job at an immigration non-profit, President Bill Clinton’s aggressive new border strategy, known as “prevention through deterrence,” was ramping up. And in Agua Prieta, a small town just across the border’s chain-link fence, a little girl named Aida Hernandez was learning to ride a brakeless bicycle and dreaming of living in New York City.

Aida would come of age with the United States’ hostile immigration policy, and her life would be indelibly marked by it. Growing up in Agua Prieta, Aida watched residents cross into the US to shop, run errands, and visit family with relative ease. But when, at eight years old, her mother takes her to live in Arizona, her future is rocked by instability; she survives years of domestic violence and becomes a mother at 16. When a misstep leads to deportation without her young son, Aida finds herself back in a Mexican city marked by violence. Her final journey to the border is in an ambulance, where her life rests in the hands of federal agents whose job is to prevent her from entering the country she calls home.

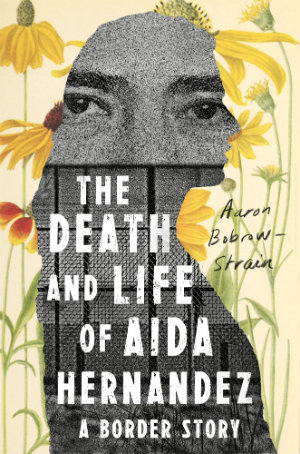

The Death and Life of Aida Hernandez (publish date April 16) weaves the personal narrative of a single immigrant with the complex history of the southern border, where many people used to feel that their culture and identity traversed the border line. For Bobrow-Strain, the violence and terror Aida experienced while trying to make a life on the edge of two nations is a microcosm of an American obsession that has consumed our understanding of our southern neighbors. Aida’s story—of border flight, immigration court, for-profit detention, and family separation—is required reading in the age of Trump. “This isn’t just a book about Aida,” he says. “It’s a book written with Aida about a world we’ve created. ”

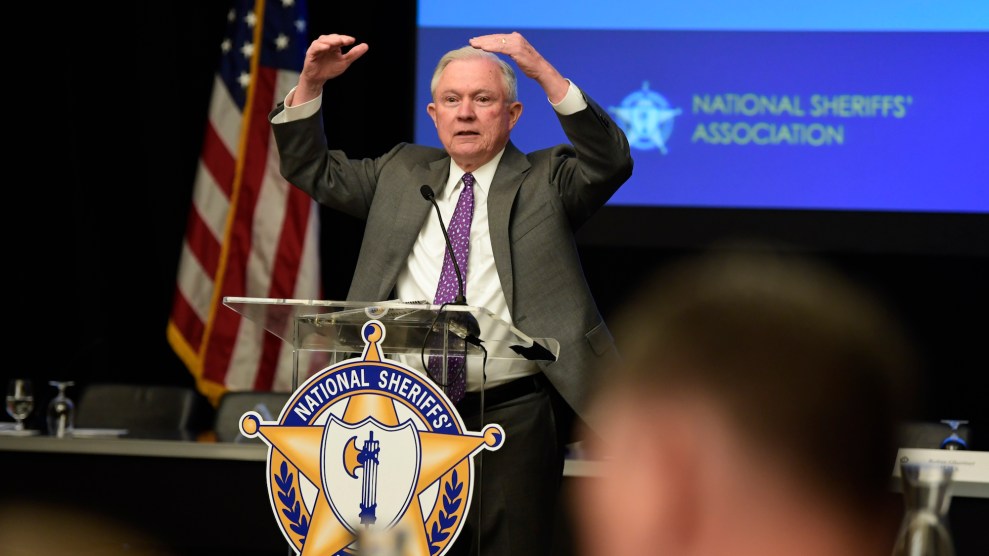

I spoke to Bobrow-Strain, now a professor of politics at Whitman College, about the way Clinton’s border policy shapes our current-day crisis, and how Aida’s story exposes the myth of the “model immigrant” in a country that set her up to fail.

This book wasn’t originally about Aida. In 2014, you went back to Arizona after more than 15 years, to write about the border. But then you were introduced to her. What was that first meeting like?

It was a powerful moment. It was a really hard story to listen to, as readers will see; a brutal story in many ways. But she didn’t ask for my pity. She was really demanding a kind of reckoning with our complicity in creating the laws and policies that made her life almost unlivable. And also, I think, expressing the way in which the act of sheer survival, in a world like the one we’ve made for her, is a form of dignity and worth, as valuable as any affluent person’s achievement.

The other thing I really took out of that first meeting was that she exuded a kind of brio and humor and wit that I think is really important, and I try to capture in the book. It’s a central piece of many immigrant experiences, but it often gets lost in the “tragic immigrant” tales that journalists write.

Her story really encapsulates many recurring themes in our current political dialogue about immigration and the southern border. I’m thinking about “zero tolerance” and family separation, the DREAM Act, and the vilification and criminalization of Mexican immigrants.

There are many twists and turns in her story, and I don’t want to give too much away. But yes—the book takes us in the world of for-profit immigration detention, immigration courts, the asylum process…Really the intimate workings of our approach to border security. We see the way low-level law enforcement officers make huge, life or death judgements about migrants in streamlined immigration processes that have no possibility of appeal. And we see that things like family separation, the criminalization of people who have been here in the United States and deeply enmeshed in U.S. communities for a very long time—all of that predates Trump.

One of the key points of the book, when I think about it going out into the world today as opposed to in 2014 when I began writing it, is that it’s really important that the book begins in 1996. Aida’s childhood and coming-of-age parallels the development of this punitive, aggressive border that we’ve created. I think it’s important to remind liberals that they can’t just get rid of Trump in order to fix the immigration system. It’s going to require a deeper examination of a 25-year-long, bipartisan obsession with “prevention through deterrence,” this costly, cruel, and ineffective program.

I was going to ask what it meant to you for the book to be published in this political moment, which you couldn’t have foreseen when you started writing back in 2014. But perhaps I’m wrong? Did you foresee that this was where we were heading?

I can’t give so much credit to my powers of prediction, but there is an arc to the history of immigration control as a form of racial control in the United States that goes back to the 1790s. In many ways what we’re seeing now is the culmination of a recent process by both Republicans and Democrats. I think, because the book is not just about the current moment, it can help us think more practically and more deeply about how we transform this system that is not working.

One thing that I think was central to my decision to write this book, that has not changed at all, is that I wanted to make a book that expanded the boundaries of empathy and justice to include people whose messy lives don’t fit into our narrow and unrealistic narrative of the “good immigrant/bad immigrant” binary. It’s really important to recognize how much of our immigration debate hinges on that idea that immigrants have to be perfect, flawless, exceptional achievers to deserve membership in the United States, no matter how deeply they are already a part of U.S. communities. Rosie Mendoza, in the book, says, “Humans make mistakes, but immigrants can’t.”

The book leads us through Aida’s life, but also navigates a swathe of complex immigration policy and Mexican-US history. Talk to me about your intention for including both the personal narrative and the political context.

Empathy isn’t enough. Personal stories reach people, and I wanted to work in that register of emotional connection. But I’ve included the history and economics and politics along with the emotional story, because empathy can reduce politics down to feeling sorry for an individual. It lets us off the hook, in some ways, from reckoning with the larger storms of structural injustice and our involvement in that.

For me, as much as I hope this book is an empathetic picture of Aida and her family, I also hope it’s a look in the mirror for more privileged folks, because all of the policies that made her life almost unlivable were created by us, in our name, supposedly to keep us safe.

What were the ethical considerations for using Aida’s story, particularly given that you aim to show her as a complex and sometimes contradictory person rather than as a purely sympathetic character?

This is something I thought about all the time, as I wrote. There’s a long history of exploitative writing on the suffering of poor people, often people of color, written for an affluent audience. For me, that meant there were practical implications for how I did the research, and implications for how I conceived the book itself. And I had to recognize the deficiencies and risks in writing a book about a young, bisexual Latina without much formal education, when I’m a highly-educated white male.

I tried to be as collaborative as possible, going back to Aida and having her shape the project. It’s really her hard-won expert knowledge about that world that ultimately drives the book. I gave drafts to other folks who are in the story and listened to their feedback, too. There was a lot of engaging with scholars and activists who are women and people of color, and really learning what they had to stay and listening to their critiques of this kind of writing. It’s not for me to say whether I’ve been able to avoid the pitfalls, but that’s what I set out to do.

You worked with Aida on the book for four years. What was that reporting process like?

I came into this via activism and ethnography, not journalism. I do draw heavily on techniques of journalism, including its commitment to verification. That meant cross-checking Aida’s accounts of her life with family members and friends, and drawing on school, immigration, court, and medical records. Doing more than a hundred interviews with immigration attorneys, physicians, community leaders, and other people to verify the plausibility of what Aida was saying and to provide broader context. And it also meant being open and transparent in the book about my methods, so readers know what they’re getting.

But ethnography starts from the idea that our relationships with others are always shaping the way we write about our subjects, and always shaping the way our subjects interact with us. There’s no detached, dispassionate research. There’s not a sense that, if we can maintain a pure distance, we can get to the objective truth.

And this is not a bad thing. Our emotions and relations are central to how we know the world; they’re powerful ways of understanding the world. There were always borders between Aida and I—class, race, gender, age—and professional boundaries, but we still went through a lot together.

What will people find most surprising about Aida’s story?

Well, folks who are closely connected to the immigrant community are not going to be surprised by her incredible resilience, her wit, her sense of pride in her ability to get through things by the seat of her pants. And they won’t be surprised by the way most lives don’t fit into the neat good immigrant/bad immigrant binary.

I think that may be a surprise for readers who are mostly exposed to the mythologies of immigration in the United States, which are about the model immigrant and the idea that you work hard and you get ahead. I think for them, there will probably be some surprises in the story.

Those myths around being a nation of immigrants are often told to reassure native-born U.S. citizens about their value and worth to their country, more than they’re actually about the lives of real immigrants.

What are your hopes for the book now?

There’s been an increasing amount of reporting on the impact of our border system on folks who are crossing the border. But I went into the book thinking about the question: what about the border communities themselves? One thing that’s really missed today is that there’s a beautiful richness to life in the borderlands. The creativity and resilience that comes from living one’s life across international borders. There can be a kind of radical hospitality in borderlands. I think it’s important to recognize that reality.

But also to understand that we’ve set those places up to be sacrificed to this 25-year obsession with hyper-aggressive, expensive enforcement. A manufactured crisis.