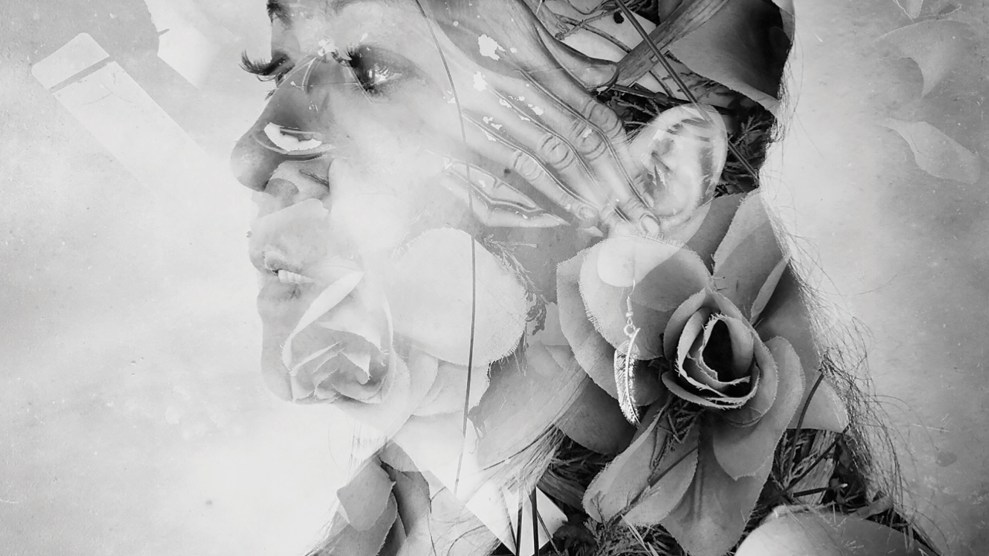

Victoria Montaño stands proudly at the BAAITS Two-Spirit Powwow on Feb 8, 2020.Delilah Friedler/Mother Jones

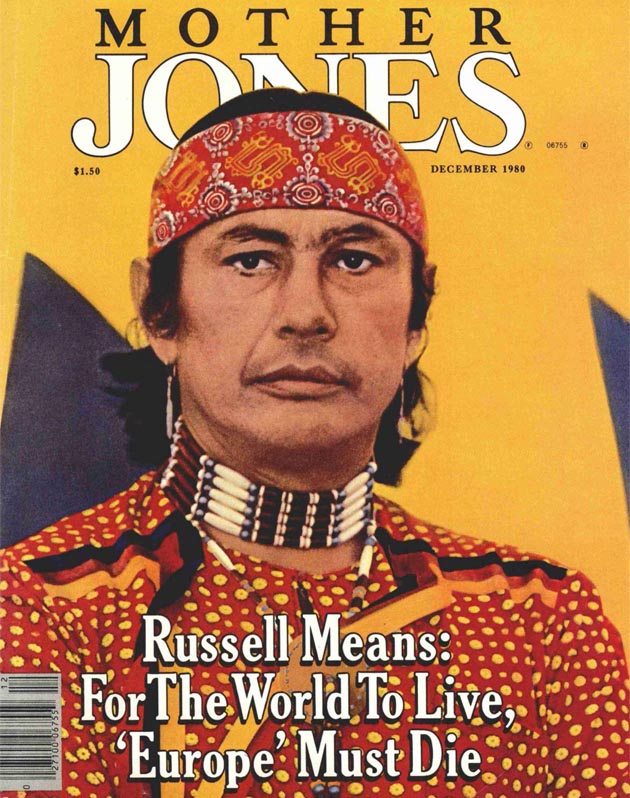

When I asked Buffalo Barbie what pronouns I should use to refer to her in my article, she smiled and batted long false lashes. “That’s in the eye of the beholder,” she said. Clad in a rose-print top, an array of bone necklaces, and copious turquoise accessories, Barbie stood behind a rainbow-fringed table selling her own handmade jewelry at the 9th Annual Two-Spirit Powwow held in San Francisco in early February. Hundreds of attendees flitted about her booth and others, while dancers festooned in colorful regalia competed in the center of the powwow, held in a spacious indoor pavilion on the city’s Presidio waterfront.

Permeated by infectious joy, the event celebrates Indigenous traditions around gender diversity. Though it’s not a monolithic category, Native American and First Nations people who combine or confound binary gender roles are collectively known as “Two-Spirits.” Generations of forced Western assimilation cast these people into the margins, but today they’re proudly emerging. “Being Two-Spirit is natural,” Buffalo Barbie told me. “It’s just being who you are. But it comes with responsibilities.”

Two-Spirit people have existed for millennia, but their English name arose in 1990, when a conference of queer Native Americans and First Nations people from the US, Mexico, and Canada translated “Two-Spirit” from a phrase in Ojibwa, the Indigenous language spoken around Manitoba, Canada, where they were meeting. “Two-Spirit” was meant to replace “berdache,” an often derogatory catch-all that Europeans used for the gender non-conforming people they met while colonizing Turtle Island (an Indigenous name for “North America”). In calling themselves “Two-Spirit,” the 1990 conferees emphasized their differences from non-Native queer people and defined themselves on their own terms.

Two-Spirit people and allies parade flags for Grand Entry at the 9th Annual BAAITS Two-Spirit Powwow.

Delilah Friedler/Mother Jones

Growing up Chickasaw in Oklahoma, Miko Thomas knew that they fell “somewhere within the LGBT umbrella,” and helped launch a group for Gay American Indians on their college campus in the 1980’s. But they didn’t hear anyone call themselves “Two-Spirit” until they moved to San Francisco, where the term was being used to describe Indigenous people who fulfilled sacred roles, embodying both masculine and feminine traits. To Thomas, this sounded like something white, gay, New Age hippies like Harry Hay would have concocted. “Where does this really come from?” they wondered.

Thomas learned that in some Native communities, people of non-normative genders and sexualities once held special status. After hearing a traditional story about the “changeling woman” who could shift her form at will, Thomas began to feel comfortable identifying as “Two-Spirit” themselves. “My expression of being both masculine and feminine is who I’ve always been,” says Thomas, who also goes by the name Landa Lakes and wore a long, green ruffle neck dress with impeccable make-up at the powwow. “Being connected to my own tribal community is what marries these things together.”

In 2001, Thomas joined a group called Bay Area American Indian Two-Spirits and soon became its co-chair. Today, she oversees inter-tribal protocols for the Two-Spirit Powwow, which BAAITS hosts to draw Two-Spirits, as well as LGBTQ+ Natives and their allies, from across the continent to San Francisco to socialize, organize, and dance. As the effects of colonization have left queer and Two-Spirit people oppressed in many Native communities, the powwow—which is free and open to everyone—”is political in nature,” says Thomas. “It’s a breeding ground for activism.”

Two-Spirit is not a singular identity, but speaks to a breadth of traditions. Cree people use the word aayahkwew for “one who is neither man nor woman,” while the Navajo/Diné have distinct terms for feminine males (nádleehi) and masculine females (dilbaa). These third and fourth gender roles work differently in each culture, but often involve spiritual functions like healing, mediating, and performing coming-of-age ceremonies.

Buffalo Barbie, Miss Two-Spirit Montana 2019, sells her jewelry at the Powwow.

Delilah Friedler/Mother Jones

At the powwow I met Dean Barlese, an elder who travels each year from the Pyramid Lake Paiute Reservation in Nevada. When he said he was a “traditional” Two-Spirit, I asked what that meant. “It means work,” he said.

In the 1980’s, Barlese’s tribal elders approached him to bestow special responsibilities, including singing ancient songs “to keep them alive” and helping bury repatriated human remains. “We bring our ancestors home from the museums and universities to work on reburial,” said Barlese. Though his gender and sexuality were not discussed at the time, he suspects his elders chose him for this role because they saw him as a Two-Spirit. “I think from a young age my community knew, and they respected it. Very few have that respect.”

In historical accounts, early colonists were disgusted with Natives who transgressed European gender norms. Government officials and Christian missionaries forced Two-Spirit people to conform, and imposed laws barring their common practice of marrying same-sex spouses. Some California Natives say that the persecution of Two-Spirit people made their communities more dependent on Catholic missions for burials and spiritual guidance. This helped coax Indigenous people into converting, thereby internalizing Christian views about gender diversity being shameful.

Having grown up in a very Catholic, patriarchal home in Texas, Javier Stell-Fresquez, who is of mixed Tigua, Piru, and European descent, was scarred with certain ideas about how she was supposed to dress and behave. But when a former co-chair of the Two-Spirit Powwow asked if she was both Native, and felt masculine and feminine energies, her answer was complicated but undoubtedly “yes.” That person encouraged her to “start representing” as a Two-Spirit.

Stell-Fresquez began to feel empowered by the term after joining BAAITS, which connected her to an ancestral legacy of queer Natives who were not just tolerated, but revered. “That helped me feel into my own gendered complexity,” she told me. “I learned that it’s about letting your gender work in a flow of what the community needs.”

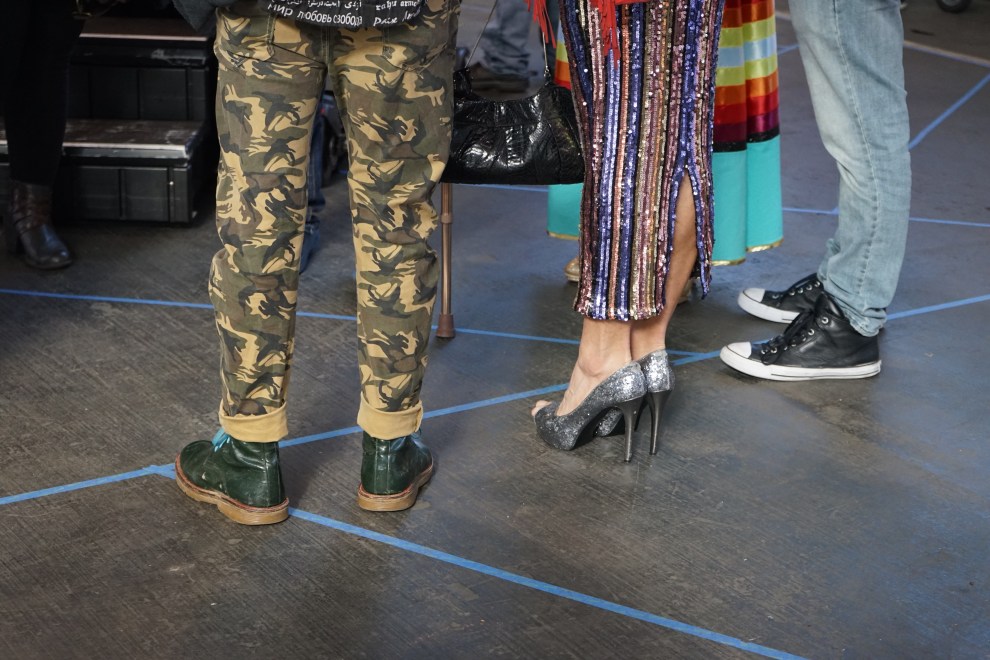

Glittery heels and platform boots danced beside moccasins.

Delilah Friedler/Mother Jones

Stell-Fresquez, who like Thomas uses multiple gender pronouns, started helping with the Powwow 11 years ago because he wanted to be with others who were striving to “remember what had been suppressed,” he said. “In many tribes, there was very utile knowledge, essential to survival, maintained through third gender roles.” A Two-Spirit person might be called upon if a family needed a mother or father, or to play other balancing roles. But, says Stell-Fresquez, “that was all disturbed by colonization. The third gender people and Two-Spirits were attacked first, and their special functions were wiped out.”

Charged political movements like the occupation at Standing Rock have brought Two-Spirits and other Indigenous people together, but powwows “are really the beating heart of Native gatherings in the US,” says Stell-Fresquez. “It keeps the blood circulating in terms of cultural exchange and inter-tribal protocol.” Much like the term “Two-Spirit,” powwows are rooted in different Indigenous traditions that have converged to form a modern meeting ground. Customs and trends spread across Turtle Island as dancers and vendors travel the “powwow circuit,” visiting multiple gatherings each year.

Powwows are arranged in concentric circles, with ceremonies and dances happening in the middle, a ring of drum circles and spectators around them, and a wide arc of vendors encircling the whole thing. After Carla and Desiree Muñoz of the Coastanoan Rumsen Carmel Tribe delivered the traditional land acknowledgment, giving thanks to the ancestors of the lands we were on, the BAAITS Two-Spirit Powwow kicked off with Grand Entry, a colorful swirl of bright neons, pastel pinks and blues, all kinds of feathers, and intricate beadwork, all displayed on dancers’ bodies in their unique handmade regalia. Stilettos and platform boots danced beside moccasins; highlighter and sequins glinted beneath indoor lights.

After Grand Entry came a series of dance competitions open to all, not just Two-Spirits. The judged categories mirrored those at other powwows, with styles like Jingle Dress, Fancy Shawl, and Northern Traditional, but the BAAITS Two-Spirit Powwow sets itself apart by allowing all entrants to dance and be judged together, rather than separating by gender. Additionally, the “Head Man” and “Head Woman” roles typical at powwows were replaced by gender-neutral “Head Dancers,” while the drum circles were opened to non-male drummers.

Marge Grow-Eppard stands beside a tipi for Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women and People.

Delilah Friedler/Mother Jones

In rows of booths, activists promoted campaigns to legalize Two-Spirit marriage and pass anti-LGBT discrimination laws in tribal communities, like bills the Oglala Sioux Tribe recently passed on the Pine Ridge Reservation in South Dakota. Representatives of the local Native American Health Center offered free HIV testing, while a number of booths expressed solidarity with the ongoing crisis of Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women (MMIW).

That cause’s loudest expression was a dark red tipi sitting just outside the facility, in the sun. Marge Grow-Eppard, who as a Mewuk person is Indigenous to northern California, raises this tipi at various Native gatherings, where those who have lost loved ones are invited to dip a hand in white paint and leave a print on the exterior. Grow-Eppard runs a group called Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women and People of California, a name that was phrased quite intentionally. “The MMIW movement doesn’t always realize LGBTQ and trans people are not represented,” she told me. “But they’re very highly at risk.” Grow-Eppard’s group is currently working to compile data on the number of missing and murdered Two-Spirit and queer Natives throughout the US.

Before leaving the powwow, I spoke with Victoria Montaño, a Mexikah and Yaqui Two-Spirit who grew up in Oakland. Montaño, who at times goes by Vic, Vickie, or Victor, joined BAAITS years ago because they were looking to get away from the queer bar scene and ground themselves in their own culture. “In BAAITS, I feel held by my elders,” they told me.

As sunlight pouring in through a gap in the roof reflected off their glowing face make-up, Montaño told me that the Two-Spirit Powwow stood for unity, visibility, and resilience. “I came to the term Two-Spirit because for me, it’s more powerful than LGBT,” they said. “Some days I represent more my masculine or feminine side, but deep down, I know that I’m both.”

An elder carries a rainbow Mexican flag for the Powwow’s Grand Entry.

Delilah Friedler/Mother Jones

Signs at the Powwow said “decolonize sexuality” and expressed support for trans people.

Delilah Friedler/Mother Jones