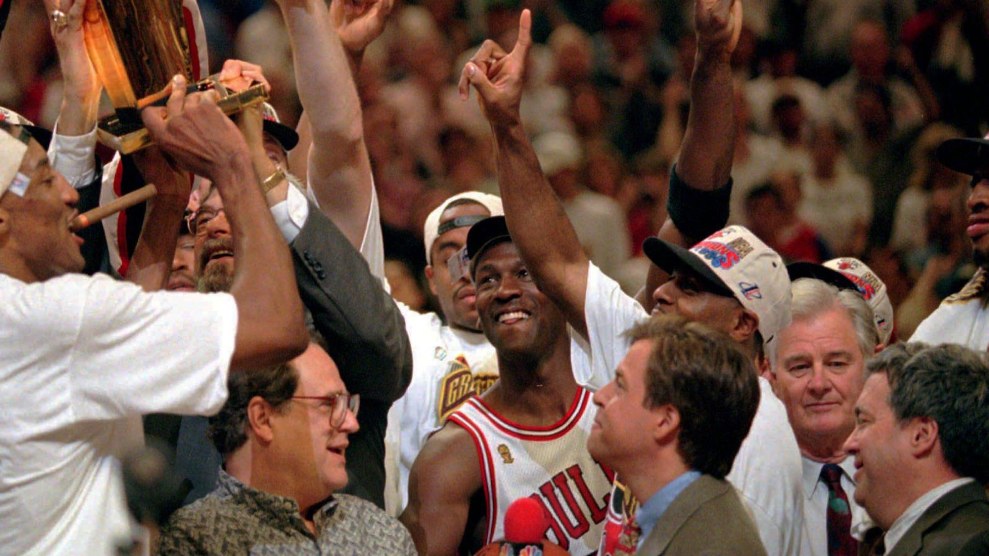

Michael Jordan celebrates his fourth NBA championship while his bosses, owner Jerry Reinsdorf (to Jordan's right) and general manager Jerry Krause (bottom right corner), pretend they did something to help. AP Photo/Beth A. Keiser

Nothing in The Last Dance, ESPN’s 10-part series on Michael Jordan’s final season with the Chicago Bulls, is permitted to be political. Not even the politics.

In episode 5, which aired Sunday, we get the story of the 1990 Senate race between Harvey Gantt and incumbent Jesse Helms in North Carolina, Jordan’s home state. Gantt was vying to be the first Southern Black senator since Reconstruction; he was running against Helms—an unreconstructed segregationist who was so racist that associating with him, as Bomani Jones of ESPN pointed out, got Lou Holtz fired from Arkansas way back in 1983. During the 1989–90 season prominent Black leaders tried to get Jordan to support Gantt’s campaign. While Jordan never replied, his mother, Deloris, heard them out and decided to make a contribution. “Anybody over Jesse Helms,” she said. And Gantt wasn’t just “anybody”—he was a “giant” of urban planning and the mayor of Charlotte. Jordan, at the time, was quoted as saying, “I really don’t know Gantt” as an explanation. Arthur Ashe fumed in his memoir years later, “Well, Michael…pick up the telephone and call him!”

You know what happened in that race. Toward the end of the campaign, with Gantt up in the polls, Helms put out his “Hands” advertisement, an infamous bit of race-baiting in which a pair of white hands are seen crumpling up a rejection letter for a job that has gone to “a minority” because of a racial quota, as a voiceover explains. Helms would go on to win by five points. Later, Jordan, apparently by way of justifying his agnosticism, would say to a friend that “Republicans buy shoes, too,” according to Sam Smith’s 1995 book Second Coming.

It’s a well-worn saga in the MJ legend, usually retailed as a morality play about the social obligations of celebrities. Here, in a documentary made in partnership with Jordan’s own production company, the emphasis lies elsewhere—it’s a story not so much about the obligations as about their toll on the celebrity forced to bear them. Barack Obama shows up to express mild disappointment with Jordan’s shrinking from any larger civic role and to explain the narrow parameters in which Black celebrities are allowed to operate. But the episode is eager to move on.

In setting up the star’s first retirement from basketball in 1993, the fifth and sixth episodes of The Last Dance pair the criticism of Jordan’s non-involvement in the Gantt campaign with the media coverage of his gambling habit, as if these two storylines were equivalent examples of undue public expectations. Politics have been stripped away. Helms and the cause he represents—certainly relevant to Jordan’s hometown of Wilmington, the site of a racist massacre in 1898 that also goes unmentioned—matter only insofar as they complicate the maintenance of a global brand. Jordan says that he made a contribution to Gantt, and that’s enough; the series never mentions the fact that the donation wasn’t until Gantt’s second run, in 1996. The Last Dance is as leery of politics as its main subject. Under twinkly music, it seems to be taking the Jordan line: Republicans watch documentaries, too.

The politics of the real world intrude elsewhere in episode 5, with the story of Croatian star Toni Kukoc, who was drafted by the Bulls in 1990. (Kukoc was “discovered” by the team’s general manager, Jerry Krause, one of many front office moves for which Krause wanted eternal congratulations.) “The situation at home was not so great,” Kukoc says impassively, “because of the war and everything.” What do we learn about this war? Other than Bob Costas explaining in some old footage that “Yugoslavia is, of course, a country divided,” we learn two things: that it kept Kukoc from joining the Bulls until 1993 and that it toughened him up for the rigors of high-level basketball. No one’s looking to the makers of The Last Dance for deep geopolitical analysis of the Balkans, but there is no mistaking the moral priorities of the series. Politics, actual life-and-death stuff, are important to the extent that they affect the basketball. (There are certainly other ways of handling the subject of basketball in the Balkans in this era. I know because in 2010 ESPN made a documentary about it.)

One tendency of big-ticket sports documentaries is to strain to show the larger stakes of the games, beyond sports. But the motion of The Last Dance is inward, away from the larger world, as if in imitation of its hero—who at this point couldn’t be more like Charles Foster Kane if you spotted him a sled and an opera singer. The doc’s myopia is Jordan’s myopia. Its obliviousness is his obliviousness. It can’t see beyond the basketball to realize that it is telling a deeply political story in spite of itself.

That story, the unwitting political story, is centered on the late Jerry Krause. (The team’s owner, Jerry Reinsdorf, gets a pass in this version.) Jordan famously hated Krause, going back to the superstar’s recovery from a foot injury during his second season in the league; Krause, Jordan maintains, kept his minutes down in the hopes of losing more games and securing a better spot in the draft. Over the years the story of their rivalry has been worn smooth into an archetypal one of jocks picking on the fat kid. (Guess where sportswriters have historically placed their sympathies.) But The Last Dance suggests there was something deeper going on there: a fight over who wins when the team wins, the bosses or the people doing the work on the court. That’s politics—a story of labor, money, race, power.

Krause, wet with champagne after a Bulls championship, pointedly crediting “the organization” and not the players celebrating around him? Politics. Krause using the prospect of a “rebuild” to keep his players and coach in line? Politics.

Lately, a fetish has developed in sports culture for what’s known as “The Process,” which refers to the management strategy of losing deliberately in the hopes of winning down the road, on the cheap. (As Jordan’s experience shows, the strategy isn’t new; the fetish is.) The Last Dance focuses on an era before fans were encouraged to identify with wily executives, but its depiction of Krause reveals The Process of the present day for what it is—a tool of player control. The goal isn’t so much to win—what did the Jordan-era Bulls do but win?—as to win on management’s terms.

Here is the accidental brilliance of the series. Behind its own back, it offers a rebuke to the notion that the suits—whose number now includes Jordan himself—could ever be the authors of basketball success. The very thought so enraged Jordan that he shaped the team into an instrument of his revenge. The Last Dance is a documentary about hating your boss and succeeding because of it. An inspiring message, in its way. Be like Mike.