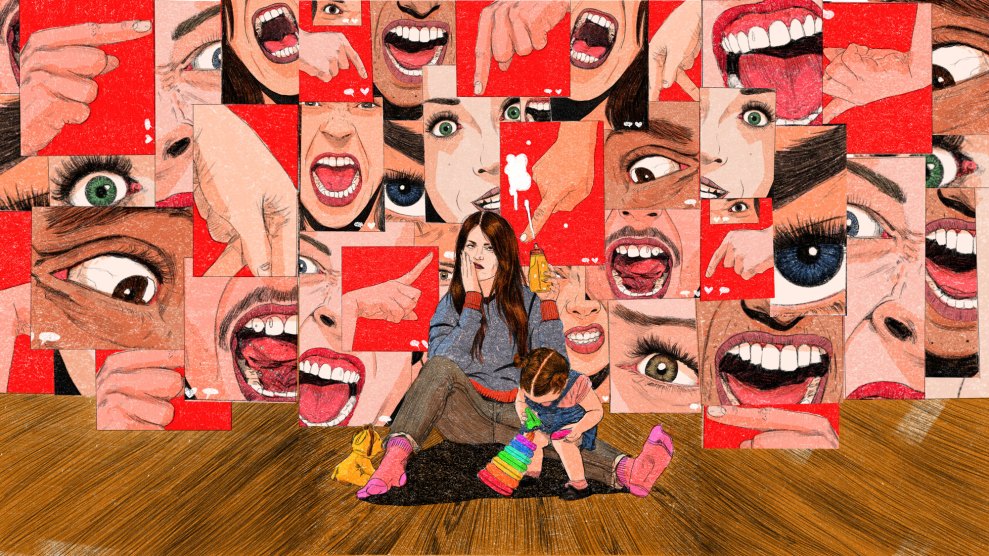

Mother Jones illustration; Paul Sancya/AP; Jose Luis Magana/AP

Jake Tapper has drawn a line: no “Big Lie” proponents on-air. The CNN anchor and chief Washington correspondent won’t book Republican politicians touting the conspiracy theory that the 2020 presidential election was stolen from former President Donald Trump. But when he’s not in front of the camera, Tapper enjoys blurring the lines between fact and fiction by crafting novels about real-life figures like John F. Kennedy and Frank Sinatra. His latest book, The Devil May Dance, is a sequel to his bestseller, The Hellfire Club, which has been adapted into a TV series by HBO Max.

During a live event hosted by Mother Jones Editor-in-Chief Clara Jeffery at the Commonwealth Club in San Francisco in early June, Tapper discussed the biggest threats to our democracy—and how his experience covering those threats as a journalist informed his work as a historical fiction writer.

Read an edited transcript of the conversation below, or tune in to this week’s bonus episode of the Mother Jones Podcast:

You told Kara Swisher of the New York Times that Republicans who push the election fraud conspiracies are not welcome on your show. How did you arrive at this decision?

I haven’t booked any of the liars since the election, but it’s not a policy. If one of them wanted to come on the show, I would talk about it with my team. I would want to talk about the election lies, not just as a throwaway at the end, but as a focus.

I think it’s important to book conservatives. But the election lies are not a difference about tax policy. It’s not a disagreement about a social issue. The election lies are lies. It’s no less a lie than saying that the moon landing was faked or that the Holocaust didn’t happen or that Bush knew about 9/11 and let it happen. These are offensive ideas.

Look, people lost their lives that day [January 6]. The truth is, we’re lucky that more people didn’t die. And so I think it is incredibly derelict for journalists just to pick up and move on.

Chris Wallace characterized your lack of interviews with people pushing election lies as moral posturing and said that the way to deal with this kind of thing is to have them on and grill them about it. You say that you’re not seeing much of that. Why do you think that is? Is it a format issue? Is it a moral courage issue?

It is not fun. It is not easy. It subjects you to attacks from Republicans, because Donald Trump so successfully convinced so many millions of Americans that facts are a partisan issue. I have yet to see Kevin McCarthy or Elise Stefanik or Steve Scalise or Josh Hawley or Ted Cruz, who I would consider to be the five who kind of led this effort—have any of them been held to account for their election lies? I haven’t seen any of one of these five grilled at all. I haven’t seen any one of those five be really asked tough questions over and over in an interview about this.

I wonder what you would say to this theory: Historically, politicians go on cable news shows and radio interviews to spin something, and so now, when confronted with the lies and bizarrely deranged theories that they’re putting forth, it’s very hard for the apparatus around producing the shows to adjust. You’re an exception, and I wonder, even within your own network, how that’s being received.

I mean, I’m given the leeway to do what I want to do. There are people who went along with this lie that I liked, that I have had on my shows before to talk about important issues. If one of these people said, “I made a mistake, I shouldn’t have voted to disenfranchise the millions of legal voters who cast their ballots in Arizona and Pennsylvania, I shouldn’t have told those lies,” I honestly would then book that person. I really would. I am just saying, I feel really uncomfortable about the idea of just letting these folks walk away from this as if what happened January 6 didn’t happen, as if they played no role.

Sort of a professional jealousy question: You’re the lead anchor of CNN. You have two shows. You had to be on hand for all the craziness that 2020 and early ’21 threw at us. You have two kids. How in hell did you find the time to write this book?

First of all, I have an incredibly supportive spouse. And my kids are old enough now, 11 and 13, that they want to spend time with me, but they don’t want to spend too much time with me.

I wrote this book in about two and a half years. The writing program is like a diet or like an exercise routine: You just have to make a rule and stick to it as much as you can. For me, the rule is, try to sit down every day and write, even if it’s just for a minimum of 15 minutes, because anybody can find 15 minutes in the day. If all you do is 15 minutes a day for a week, that’s an hour and 45 minutes. That’s three or four pages, and it adds up.

I will also say that I wrote a lot of this during the pandemic. I did the show from my house from April to August, and I found myself with a lot more time than I ever had in my life.

Charlie and Margaret Marder are the protagonists of both your books. The first book, The Hellfire Club, was set in DC in the McCarthy era. What made you choose to set this book in Vegas and Hollywood in ’62?

Right around the time that I realized that people were buying the first book and that I was going to be able to write a second one, I heard this amazing true story. Frank Sinatra and the Rat Pack worked their hearts out to get Sen. John F. Kennedy elected in 1960. It was a very narrow election, and also a member of the Rat Pack was married to Kennedy’s sister.

Sinatra thought that President Kennedy would would come stay with him when he came out to California. He started having all this work done to his estate near Palm Springs. He had rooms put in, he had phone lines installed, he had a helipad constructed.

And then it’s pointed out to Attorney General Robert Kennedy, who was going after organized crime, that Sinatra—who’s friends with the president—is friends with Chicago mob boss Sam Giancana. So Robert Kennedy had this dilemma: Do I insult one of the biggest stars in the world, a friend of my brother’s who helped get my brother elected through ways known and secret? Or do I let my brother sleep in a bed where monsters have slept?

So when I heard that story, I said, I need to have Charlie and Margaret go into that, because I can keep playing with the Kennedys, and now I can add the Rat Pack, and it just sounds fun.

Your job as a journalist is to unearth truth about powerful people. When you put on your novelist hat, you’re also inventing some tales about them. Tell me how you thought about that tension.

You have to just let yourself make stuff up because it’s a novel, but you try to be true to the idea, to the essence of the person. Marilyn Monroe, for example, appears a few times in the book, but I never could figure out how to write her into the book in a way that rang true.

You invented a Sinatra song. The title of the book is the title of the song. What did you do to ensure that these are in the style of lyrics that Sinatra would have sung?

When I wrote The Outpost, which is a nonfiction book about Afghanistan, there was a scene where the guys are cranking up AC/DC. There’s another scene at the end of the book, after the big battle where eight of their brothers died, where they’re singing Johnny Cash songs. I had to take out everything except for one line because the attorneys for Little Brown said, “You can’t quote more than one line, or we’ll get sued for copyright infringement.”

So this is frustration over the limits of “fair use“?

Yep. Entirely. The lawyers called me up and they’re like, Tapper, we’ve been through this. You have an entire song intricately woven into this action scene at the climax of the book. And I’m like, “I wrote the song! It’s not a real Sinatra song!”

Every profile that I’ve read about you has described to you as being very confident from a young age. Which came first, the confidence or the accomplishments? And what would you say to young journalists who are maybe a different gender or a different race?

First of all, I’m plenty insecure, like any other human being on the planet. One of the things I say to young people constantly, because I don’t think anybody prepared me, is that there is a lot more rejection out there than you have been raised to believe there is in life. There’s a cocoon around you when you’re young. Maybe you didn’t get the part you wanted in the school play. Or maybe the boy or girl you liked didn’t like you back. But generally speaking, you get a lot of what you want. Then you go into the real world. People just need to be ready to be rejected. Every successful person you see in journalism has been rejected so many times by so many people. It’s just part of it.

I think there’s probably never been a better time to be a woman journalist or a journalist who’s Black or Latino or Asian. I’m not saying that it’s easy. It’s still much easier to be a white male journalist, don’t get me wrong. But at least now it’s part of the conversation in a way that it wasn’t when I was coming up.

What part of your job do you enjoy the most?

I love doing my show. We cover news from all over the world. Whatever you think of Trump, him not being in the White House means that I now have time in my show to do a piece about foster care in America, or about the elections in Nicaragua. I’m proud of that.

That’s an entire show. Is there a part that particularly charges you about the making of any one show?

I mean, when I have a good, tough interview with somebody, it’s fun.

Stephen Miller, perhaps? That was a classic.

But that wasn’t pleasant. I would have really honestly preferred him to have been a normal human being, answering my questions, but he was performing for his audience of one. I haven’t watched it. I did Fresh Air a few years ago and they played me a chunk of the interview, and I couldn’t believe in retrospect how patient I was with him.

I worry about our democracy. In a way, I worry more than now than I did before. I think people don’t really fully understand how close we came to the election being stolen.

And how they’re setting up to enshrine the ability to do it again.

That’s what I’m worried about, because now they’re changing laws in states like Georgia to make it easier for a state legislature to overturn the will of a secretary of state, like Brad Raffensperger, who abided by the law and stuck to the facts, and now may well not be reelected. I think people don’t fully understand necessarily that if like 15, 20 different people were in those positions, the election would have been stolen. And I don’t know what would have happened. I mean, would there have been another civil war? What would have happened?

What was happening at the network when that was going on?

We were playing it straight as it was during that time. I don’t know what they were saying on other networks. We were just saying what was happening. I’m afraid of what’s going to happen next time.

I think what’s interesting about this moment is that Trump still holds sway. I think it’s a scary new moment for the country that I am not sure people fully understand either.

I mean, you just have to look at Liz Cheney. I’m sure you agree with her about almost nothing, but you just have to look at what she did. It’s such a joke when the MAGA people say that Liz Cheney did that to be popular at cocktail parties. What cocktail parties? It’s such nonsense. There’s no upside for Liz Cheney other than she can sleep at night.

With our country being so divided politically, what gives you hope that we could come closer together? Or are you in a sort of ebb of hope at the moment?

I’m never without hope for this country. And other countries have their problems, too. It’s not like I look at any other country and say, they’ve got it figured out. I think that it’s a time for politicians to really think about what’s more important: their own individual pursuit of power, or the country?

Look, I’m not a liberal Democrat. I’m not advocating that Joe Biden be reelected. I just think it’s important that these very nefarious lies be called out.

Watch the full, unedited live event below: