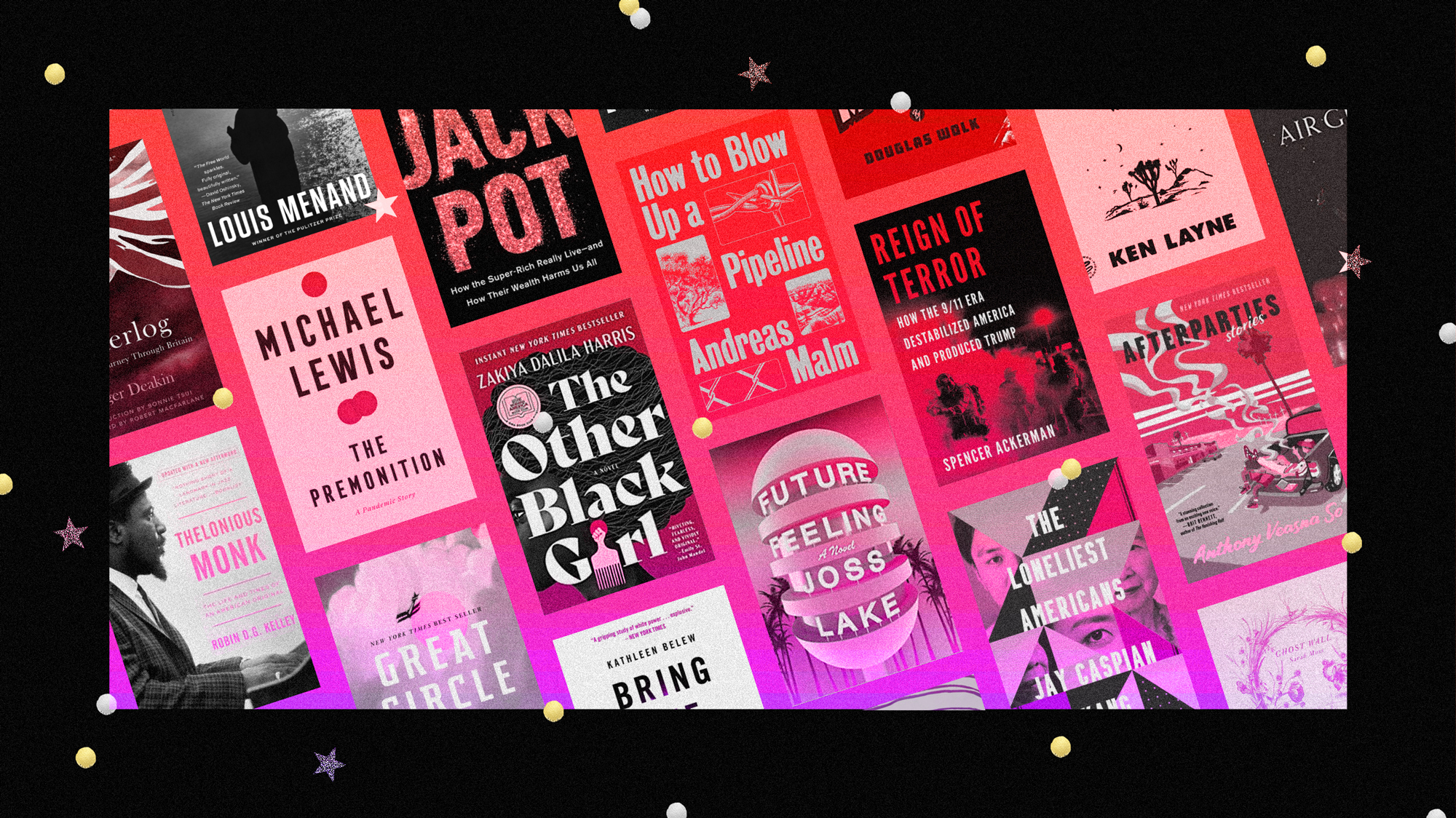

The New Books We Loved

Nonfiction

All of the Marvels: A Journey to the Ends of the Biggest Story Ever Told, by Douglas Wolk. Superhero comics are a notoriously impenetrable medium, prone to self-indulgent references and indecipherable plot mechanics, even as they’ve provided fodder for the most successful movies of our time. For as delightful and surprising as comics can be, overcoming their interwoven complexity can feel like homework. Douglas Wolk’s All of the Marvels is a fitting antidote. Wolk, an engaging and generous critic, structures his book as a part-guide, part-reflection on the nature of Marvel’s decades-long, interconnected narrative, which he consumed in its entirety. That’s right—Wolk read every comic Marvel has published since 1961, totaling roughly 27,000 issues. The stunt provides some of the book’s best laughs—you would be surprised at what bizarre stuff Marvel has published—but Wolk never leans on his expertise to be didactic. Instead, he uses his experience to become the best kind of inclusive host. His book promotes a version of comics fandom that barely resembles the kind often seen on the internet. New readers, in his telling, need not submerge themselves in lore, even for stories that appear to demand it. They just need the service of their own imagination and a willingness, like so many Marvel fans, to keep exploring. “What the story wants from you is not your knowledge but your curiosity,” he writes about one particularly dense comic set during the 2015 crossover event Secret Wars. “You are not ‘unprepared;’ you are already the ideal reader.” —Dan Spinelli

The Free World: Art and Thought in the Cold War, by Louis Menand. In (sometimes a bit too) siloed chapters, Menand walks you through just about every “major thinker” one could imagine from the Cold War era: Jackson Pollock, James Baldwin, Allen Ginsberg, George Kennan, Hannah Arendt, Claude Lévi-Strauss, John Cage, Susan Sontag, the Beatles, Isaiah Berlin, Elvis, etc. Menand, ever the professor, is masterful at distilling life works into concise and understandable paragraphs. As Mark Greif noted in the Atlantic, this can feel almost too scientific, at times—as if we’re reducing the quest for truth into dissection and Menand is the “world-class entomologist.” Still, I have never learned so much so quickly in my life. Well, except for the other time I read a Menand book. A bonus for reading The Free World: It led me to this fantastic, very long John Cage song—a series of electronic noises and a story about teaching a class on mushroom identification. It is, like most things good, so weird. —Jacob Rosenberg

How to Blow Up a Pipeline, by Andreas Malm. If you want to do something about the climate crisis instead of wallowing in despair, there’s no better place to start than Andreas Malm’s short treatise on the virtues of eco-sabotage. In 2007, Malm, a Swedish activist, joined a campaign to deflate the tires of wealthy SUV owners in Stockholm. Now he’s suggesting more drastic vandalism. His latest book—which, as others have pointed out, explains not how but why to blow up a pipeline—dismantles the notion that successful protests are necessarily nonviolent and provides a roadmap for effectively mobilizing the currently stagnant climate movement. No, it doesn’t fully grapple with many people’s unwillingness to go to prison in the name of saving the climate. But it does provide a radical sort of hope for those bold enough to take the destruction of carbon-emitting infrastructure into their own hands. —Abigail Weinberg

Jackpot: How the Super-Rich Really Live—and How Their Wealth Harms Us All, by Michael Mechanic. The “very rich…are different from you and me,” F. Scott Fitzgerald once observed. “Yes, they have more money,” Hemingway quipped years later. (The story is a little more complicated than that.) And in his new book, Michael Mechanic, a colleague of mine at Mother Jones, says the top .01 percent are different and, then again, they’re not. He spent years exploring the world of the super-wealthy, chronicling the well-off in their natural habitats: the luxury car dealership, the wealth management office, the ultra-lovely home, the personal security company. Offering more than voyeurism—the vacations! the mansions!—he deftly shows the many ways the system is rigged in their favor so that wealth perpetuates greater wealth. Along the way, Mechanic documents how the huge income gap in the United States affects its social fabric. “Our strike-it-rich aspirations,” he writes, “might be harmless if not for one inconvenient truth: The wealth fantasy, combined with the peculiarly American notion that anyone can succeed via grit and smarts and hard work, leads us not only to tolerate mind-blowing economic unfairness, but to support the kinds of policies that produced this mess in the first place.” It was dirty work scrutinizing the challenges, foibles, and injurious actions of the rich. But we should all be glad Mechanic took on this task, and, at least, he got to cruise in some very fine rides along the way. —David Corn

The Loneliest Americans, by Jay Caspian Kang. The most discussed and debated part about Jay Capsian Kang’s part-memoir, part-history, part-argument are its contentions about the limits of the term “Asian American.” Kang doesn’t make a case for abolishing the term, but he scrutinizes its limitations. While his arguments focus on Asian Americans, many have universal, or at least broader, applicability. One of the core contentions of Kang’s book, as he describes in an episode of his podcast, Time To Say Goodbye, is that “I don’t think that the process of only using trauma through history…to create an identity and stories of overcoming to construct an identity that connects people who might have a privileged class position to be able to buy into that type of identity and trauma,” makes the most sense. In The Loneliest Americans, Kang isn’t making a class reductionist case, but is asking for something more nuanced than “we are from the same continent, so we have the same concerns” (my words, not his). In this way, The Loneliest Americans offers a useful update for how race is processed and talked about in popular discourse. —Ali Breland

The Premonition: A Pandemic Story, by Michael Lewis. America is the richest, best-resourced nation on the planet, with the industrial might and scientific expertise to tackle any problem we deem a priority. So how is it we’ve lost more of our own to the coronavirus pandemic—more than 800,000 officially, though the actual toll is probably closer to 1 million—than any other nation? You might be tempted to say, “Donald Trump!” But he’s only part of it. When Lewis set out to write a pandemic book, it did feel to him like a logical extension of his previous one, The Fifth Risk, which was more or less about Trump. But in this case Trump was a “comorbidity,” he discovered. The problems ran much deeper. For one, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, that trusted constellation of federal research agencies we turn to for leadership in such matters, was a leviathan ill-equipped to move fast enough or make the career-wagering decisions required to stave off mass death. The president was almost comically inept, yes, but “it isn’t that Donald Trump is taking this exquisitely tuned, polished machine and destroying it. He’s taking this machine that we’ve allowed to gather rust for more than a generation and taken a sledgehammer to it,” Lewis told me in an interview. So he set out to tell the story as only Michael Lewis can. Harnessing a cast of unexpected protagonists—a stupendously creative biochemist, a physician/savant working in the bowels of the Department of Veterans Affairs, a public health officer whose fiery determination is matched only by her willingness to subvert hierarchies—he paints a riveting portrait of system failure. “I basically took a flying leap. I became so interested in the characters, I just said I’ll trust them to get me through the story,” Lewis said. And they do. This trio of stars, plus myriad side characters, are the conduit for this quasi-novelistic, un-put-downable tale of curiosity, bravery, heroism, and institutional dysfunction, with potent lessons for the remainder of this pandemic and the next one, and the next. —Michael Mechanic

Reign of Terror: How the 9/11 Era Destabilized America and Produced Trump, by Spencer Ackerman (2021) and Bring the War Home: The White Power Movement and Paramilitary America, by Kathleen Belew (2018). Economic anxiety as the explanation for why swaths of the American electorate have become open to increasingly extreme, far-right politics, never fully made sense. The white, boat-owning, car dealership local elites who went heavy for Trump don’t experience much economic anxiety beyond “how few taxes can I get away with paying,” which is also a concern of wealthy liberals, who didn’t vote for Trump. Even at the furthest pole of the right, the white power movement, economics don’t paint a full picture of what drives people to extremism. Instead, historian Kathleen Belew pinpoints the blowback of America’s imperial pursuits overseas. Going to war abroad, Belew spells out in 2018’s Bring the War Home, is the surest way to generate a groundswell of racist, far-right extremism domestically. While Belew primarily focuses on the white power movement in the 70s and 80s, in his 2021 book, Reign of Terror, Ackerman carries her thesis into the current moment, connecting how George W. Bush’s forever wars boomeranged to helped galvanize the Islamaphobic, white power extremists who are rising up right now. —A.B.

Waterlog: A Swimmer’s Journey Through Britain, by Roger Deakin. After DC closed all the city’s pools at the beginning of the pandemic in 2020, I started swimming with a masters’ team in a brackish river that feeds into the Chesapeake Bay near Annapolis, Maryland. The water was brown and cold—we started out in wetsuits—and then as it got warmer, the river filled with jellyfish and boats. But there were also osprey, friendly teammates, and blue sky. Swimming in nature proved to be the perfect antidote to the claustrophobia of lockdowns.

Roger Deakin would have understood. In 1999, the late British naturalist published this delightful account of his swims through weirs, fens, canals, and swimming holes across the UK—a tour he conceived of while breaststroking in the moat around his house, in the rain. He is lonely and isolated after a breakup; his son had decamped to Australia to go surfing. There is “no antidepressant quite like sea-swimming,” he decides. Deakin dons his snorkel and crashes fishing clubs, splashes through aging lido pools, dodges man-eating pike, marvels at water skeeters and leeches, and makes friends with other lads violating government swimming bans in public waters. He quotes Wordsworth and finds adorable tales about local swimming heroes in ancient British swimming magazines and writes sentences like this: “Made ravenous by the cold water, I demolished a prosaic sandwich lunch reclining on a cushion of thyme, with my head resting on a clump of moss the size and texture of a British Railways antimacassar.” While the book was a bestseller in the UK, it had never been published in the US until this year. The American edition includes an intro by Bonnie Tsui, who in 2020 published another fine addition to the swimming canon, Why We Swim, which I also read last summer and heartily recommend. —Stephanie Mencimer

Fiction

Afterparties, by Anthony Veasna So. The narrators in these short stories—mostly second-generation Cambodian Americans, mostly young gay men at the cusp of adulthood—spend their days in the grocery store backrooms, doughnut joints, auto-repair shop offices, and threadbare backyards of Stockton, “a dusty California free of ambition and beaches,” as the striving younger brother in the story “The Shop” describes his hometown. The invitation into these overlooked spaces is part of what makes these stories so magical; their characters’ scrappy ambitions and yearnings and inextricable ties to one another help, too. As does their potent alchemy of humor and pathos, a signature of the genre’s greatest works. One narrator observes that the smog technician in his father’s auto shop “cracked a joke about always finding himself in oppressive regimes—first under Pol Pot, then under his wife…which made Dad laugh and laugh, and when he stopped laughing, and his eyes caught mine, I saw it, that look of faint, enduring grief.” Afterparties carries with it a similarly sad aftertaste: So died in December 2020 from an accidental drug overdose, months before his “post-khmer genocide queer stoner fiction,” as he described his debut, was released (a posthumous book will hit shelves in 2023). In his short time on the planet, So set the page ablaze with his tales, and you’d be a fool not to pick them up. —Maddie Oatman

Future Feeling, by Joss Lake. The future in Lake’s debut novel is not far off from the reality we currently inhabit. In the 20–s, subway cars change color depending on the commuter’s mood and influencers with large enough followings transform into holograms, their images beaming out of phones. The protagonist Pen, a gloomy trans dogwalker, stews each day while doomscrolling posts of a seemingly perfect trans influencer Aiden Chase. After meeting Aiden irl, Pen places a hex on his idol/nemesis, which accidentally hits Blithe, a different trans guy, and sends him to a depressive realm called the Shadowlands. Together, Pen and Aiden journey cross-country from the bleak beauty of the Salton Sea to New York City to shepherd Blithe out of the darkness with the help of the Rhiz, an omniscient trans organization. This hilarious and sexy book brings new meaning to the sci-fi genre as it dives into the nuances of t4t friendships, kink, magic, and the pitfalls of obsession. With wry humor and cultural critique so sharp you may slice your finger, Future Feeling imagines what it might look like to be trans in the future: one that is oversaturated with data and frictionless tech, yes, but one in which trans people are centered, cared for, and where mutual aid has our backs. In a year where dystopian tech and attacks on trans rights dominated my reporting beat, this delicious novel was the perfect antidote. —Lil Kalish

Great Circle, by Maggie Shipstead. Airports bustled again in 2021, though I mostly flew to the places I’d already been to reconnect with the people I missed dearly after a year of isolation. These trips were filled with intense anxiety about COVID and social connections that had been frayed by distance. Travel became so stressful, I forgot why I ever aspired to it in the first place. Enter Maggie Shipstead’s newest novel, Great Circle, an epic saga following the life and ambitions of aviator Marian Graves from her rescue off a sunken ship in 1914 to her doomed attempt to circumnavigate the globe through both the north and south poles in 1950. Marian’s great circle around the globe is, by design, a journey without a destination; flight for the sake of flight itself. Reading from the apartment I spent much of the pandemic in, it wasn’t that I was transported to new or exotic places in the way readers so like to talk about, but that I was returned to a mindset of hungering for something more. The 608-page epic is broken up by a section of first-person chapters from the A-list Hollywood actress set to play Marian in the indie biopic about her final journey. Though these sections generally lack the depth, detail, and intrigue of the chapters about Marian, one that struck a chord with me was a psychedelic-induced reflection from the actress on the glitz and grit of Los Angeles. I read this meditation in the midst of planning my move from Los Angeles after six years of growing up in the city, and her words had me seeing the poetry of a place that until then I was desperate to escape. Such was the magic of Great Circle, a novel that made me want to finally stir from my safe pandemic huddle, but also appreciate the exact place I was already in.—Ruth Murai

The Other Black Girl, by Zakiya Dalila Harris. In a Midtown Manhattan publishing house, our protagonist, a young Black woman named Nella, is an editor’s assistant toiling away to impress the cultural gatekeepers (none Black) and hoping to become one herself. It’s a tightrope, of course. Beyond the usual minor indignities people of color endure in a largely white workplace, Nella is called upon, for example, to vet a problematic Black character in a prominent white novelist’s manuscript. If she says what she truly thinks, she’ll offend a star client and perhaps derail her career. But if she doesn’t say anything, how will she face herself? Nella’s reality, in any case, is upended by the arrival of a new editorial assistant, Hazel, the titular Other Black Girl. She’s charming, authentic, confident, and seems—at first—as though she might be a blessing. The predictable path for such a novel would be the formation of an uncomfortable rivalry as the two young women jockey for position—kind of like that Key & Peele routine where Key tries to join the a cappella group in which Peele is the lone Black dude who now feels threatened. And yeah, a workplace rivalry is certainly part of this story, but it’s a bait and switch. Zakiya Dalila Harris doesn’t do predictable. She takes the setup in a fantastical direction that I really did not expect. The result is weird and tense and fun and would make for an excellent TV series, and—ah!—it turns out Harris is working on just that with producer Tara Duncan. So no more spoilers. But you’d better go read The Other Black Girl now, lest you one day be tempted to binge it on Hulu instead.—M.M.

The Older Books We Needed

Air Guitar: Essays on Art & Democracy, by Dave Hickey (1997). In November, the writer Dave Hickey died. Other tributes will do fuller justice to him—he could resemble the “enfant terrible” slash “dirty uncle” of art criticism. He liked Las Vegas, jazz, and ripping inauthenticity to shreds. Of his own work, he said in an interview, “My job is to mow stuff down.” He was the best critic of critics I’ve ever read. I disagreed with half of what he wrote—and yet it was the way he wrote it. There is a tension in his work in that he’s probably yelling, to a certain extent, at you. I read his collection throughout this past year after an editor recommended it to me, and then I recommended it to others, and now in a short time I’ve come to consider it a totemic text. The subtitle is one of my favorites ever: Essays on Art & Democracy. Jesus Christ, isn’t that perfect? Even the ampersand. I am rereading it again now.

And in each of the 23 essays (“love songs,” he calls them), he’s startlingly alive on the page. One of the essays, called “Romancing the Looky-Loos,” I keep as a PDF on my laptop, for inspiration. I go to it looking for little turns of phrase. Maybe I go to it, too, to understand a bit how to live. It’s about being in a punk club, and the “looky-loos” come in. They are the critics. The “spectators.” They don’t contribute anything. They want to harvest instead from what has been made. This is sacrilege to Hickey. Beyond the “hegemony of corporate and institutional consensus” past “uncannily lifelike blockbusters like Jurassic Park and the Whitney Biennial,” Hickey notes, “everything that grows in the domain of culture, that acquires constituencies and enters the realm of public esteem, does so through the accumulation of participatory investment by people who show up.” That means you need to do something. Because “nothing transpires that does not float upon the ephemeral substrata of ‘word of mouth’—on the validation of schmooze.” So, go out there. Make something happen. There’s your purpose. —J.R.

Desert Oracle: Volume 1: Strange True Tales from the American Southwest, by Ken Layne (2020). I first picked up a copy of Desert Oracle, a quarterly magazine published by the former Wonkette editor Ken Layne, about six years ago at a bookstore in Bishop, California. It was engrossing in its lo-fi simplicity—inside a 40-page mustard-yellow booklet stapled together like a zine, there was a story about a phone booth, a dispatch from a land auction, and a profile of a ringtail cat. It cost $3.95 and it was perfect. It was not, however, especially punctual. Layne was mostly a one-man operation and issues came out when they came out. At the end of Desert Oracle: Vol. 1, an anthology of his pieces for the magazine (and its offshoots, which now include a podcast and a radio show), Layne thanks subscribers for their patience: “Maybe I’ll get caught up next year,” he writes.

But that’s all fine, honestly, because Vol. 1 is packed with enough rabbit holes and musings to keep me going until those next issues come. Layne, an exile from the hellscape of political blogging, has spent the ensuing years exploring what he’s truly passionate about—occultists, hucksters, unidentified flying objects, Edward Abbey, La Llorona, the radio show Coast to Coast A.M., secret government test sites, nature, myth, land, underground cities, whatever. It’s weird and fresh and smart and sometimes meditative but never in an overwrought or bad way. Here’s hoping we get a Vol. 2. —Tim Murphy

Ghost Wall, by Sarah Moss (2018). What a strange spell of a book. In 1970s England, Silvie’s father has dragged his family into an Iron Age reenactment experiment for the summer; along with a university professor and his class, they eat wild game and sludgy porridges, and forage in the dense forest in abrasive tunics and inadequate footwear. A project that seems quaint on its surface belies something much more ominous, which Moss masterfully builds toward with taut scenes, an unforgettable protagonist, and a natural landscape so richly rendered it nearly sprouts off the page. Violent and haunting, this slim novel suggests we are doomed inside the cages of our biological differences. And yet, it also manages to find hope in the friendships forged in the darkest swamps of experience. Ghost Wall catapulted me out of an isolating year into a sinister slice of history, while also making me grateful for the many strong women who have my back. —M.O.

Hunger, by Knut Hamsun (1890). I’ve spent intermittent points of the last two years chugging through Karl Ove Knausgaard’s My Struggle series, which means I’ve seen enough references to Hamsun’s Hunger to finally pick it up. Knausgaard and Hamsun are both Norwegian. And Hamsun, like the guy Knausgaard tries to alpha-dog with the title of his six-part opus, was an enthusiastic Nazi. There’s nothing obviously Nazi-ish in the magnum opus of a man who would personally meet Hitler. Instead, Hamsun takes you deep into the world of a freelance journalist and vagabond wandering around Oslo (then called Christiania) as his mind slowly unravels from malnourishment. Even amid this, the narrator (modeled after Hamsun’s own experiences in poverty), maintains a code of ethics, sometimes giving what little he has to other poor people, and turning himself in for stealing. The book is brutal, tragically funny, and good. In reading it, its influence becomes apparent. Not just on Knausgaard, who grew up in two Norwegian towns linked by a road that Hamsun lived on, but so many other 20th-century writers who came after him. Despite his influence, Hamsun isn’t a household name, which is his own fault (people don’t like Nazis). Regardless, reading Hunger feels like accessing a blueprint for so much of what came after it. —A.B.

John Brown, by W.E.B DuBois (1909). “When a prophet like John Brown appears, how must we of the world receive him?” writes W.E.B DuBois in his 1909 biography of the abolitionist martyr, who was executed by hanging 162 years ago this month for his attempted raid on the United States Armory in Harpers Ferry, West Virginia. Inspired by Ethan Hawke’s portrayal of Brown in Showtime’s 2020 limited-series The Good Lord Bird, an adaptation of the James McBride novel, this year I picked up one of DuBois’ lesser-known works. Like The Good Lord Bird, where Brown is filtered through the narration of the fictional Black protagonist Little Onion, DuBois’ biography looks at Brown as a white figure within Black history. This is in stark contrast to the historical narratives of the Lost Cause and Dunning School that portrayed Brown as a genocidal lunatic and the emancipation of Black people a horrible mistake. Because of this, the biography is largely a redemptive project, recasting Brown as a prophetic abolitionist hero whose life is owed as much attention and reverence as his death. The book reads like a warm-up to DuBois’ 1935 magnum opus Black Reconstruction, where he would fully refute what he called “The Propaganda of History” that helped reinstate American apartheid. In Brown, DuBois saw a man whose “leadership lay not in his office, wealth or influence, but in the white flame of his utter devotion to an ideal.” The most stirring passages come when DuBois uses Brown as an entry point to contemplate religious conviction, morality, free will, and human purpose. In the second to last chapter, entitled “The Riddle of the Sphinx,” he writes, “We are but darkened groping souls, that know not light often because of its very blinding radiance. Only in time is truth revealed. Today at last we know: John Brown was right.” —Eamon Whalen

Parable of the Sower, by Octavia E. Butler (1993). It might sound odd that a book about the climate apocalypse and humanity’s descent into assault, addiction, and virulent capitalism comforted me most this year. But it did. Like many others who rediscovered Butler’s words over the last years of political chaos, I was in awe of the wild accuracy of her writing. (Butler herself speaks on this: “I didn’t make up the problems…All I did was look around at the problems we’re neglecting now and give them about 30 years to grow into full-fledged disasters.”) The book is a collection of fictional journal entries from a young woman named Lauren who is in the process of making sense of a quickly deteriorating world. Born with “hyper-empathy,” a condition that causes her to feel the physical and emotional highs and lows of others as if she were them, Lauren finds herself on a pilgrimage from southern California to the Pacific Northwest. Along the way, Lauren develops a type of theology-ideology-hybrid that unfolds as she learns to navigate a world ravaged by our fellow humans. It purports that humanity’s place is among the stars.

Something I’ve struggled with a lot this year is an ever-creeping sense that the collective “we” are growing meaner and more hostile toward each other. Maybe that’s an American feeling. Maybe it’s personal. The reality that Butler creates for Lauren is terrifying for a lot of reasons that we can conceptualize all too well right now: rampant wealth inequality, disconnected politicians, overwhelming pollution, people turning to substances to escape capitalism’s tentacles, etc. And yet, there’s a throughline here Butler delicately weaves: community. Learning how to trust each other and live together is their saving grace. It might just be ours, too. —Sam Van Pykeren

Thelonious Monk: The Life and Times of an American Original, by Robin D.G. Kelley (2009). Fleeing violent racism and economic stagnation in the postbellum South in the early 20th century, hundreds of thousands of African Americans moved north to cities, where they found more segregation and hatred, but also forged a new vision of multiracial US metropolism. Among the many enduring artifacts to emerge from this monumental shift was the greatest American avant-garde art form: modern jazz. The gloriously weird pianist-composer Thelonious Sphere Monk embodies this epic tale. Born in Rocky Mount, North Carolina, in 1917, he moved to the San Juan Hill section of Manhattan’s West Side in 1922, where he lived for most of the rest of his life. During the mid-1940s creation of bebop—jazz’s pivot from dance music to art music—Monk was there, pounding the keys at Minton’s Playhouse, the then-obscure Harlem Club, while trumpeter Dizzy Gillespie (born in South Carolina, 1917) and saxophonist Charlie Parker (Kansas City, 1920), among others, worked on riffs that still echo through the culture. In UCLA professor Robin D.G. Kelley, the great historian of social movements and a jazz fanatic, Monk and modern jazz itself found their ideal biographer.

In the depths of 2021’s grinding weirdness, I found solace in rediscovering classic jazz while devouring his 2009 masterpiece. Kelley has the stylistic chops to plunge us into Monk’s drama: his steadfast, decades-long slog of conjuring up immortal melodies while living in broke-ass obscurity, tutoring upstarts like Miles Davis and Sonny Rollins in his tiny apartment, and enduring the persecution of racist cops for his weed habit. While doing so, Kelley expertly knits the tale into the broader currents of US history, from the Great Migration to World War II to the civil rights movement. This is one to read with your Spotify app handy to track Monk’s sonic progression, and a good bottle of bourbon nearby. —Tom Philpott