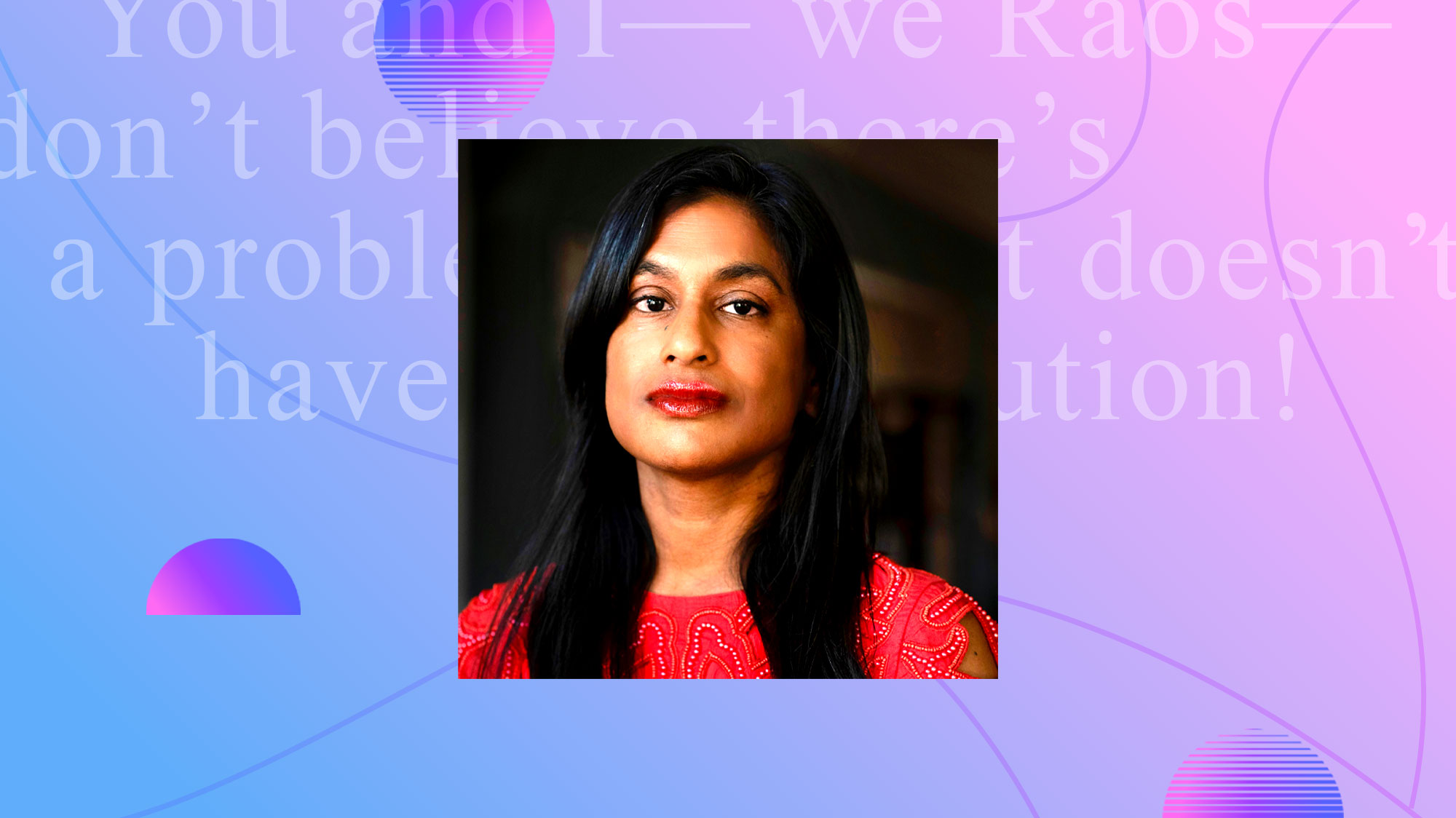

Vauhini Vara didn’t set out to write about tech lords. After spending several years as a Wall Street Journal reporter in the 2000s, she left journalism to do an MFA at the Iowa Writers’ Workshop and work on short stories instead. She didn’t expect her experiences trailing Larry Ellison and Mark Zuckerberg to inform her fiction craft; “I didn’t think I was going to write about it,” she told me via Zoom from her home in Fort Collins, Colorado.

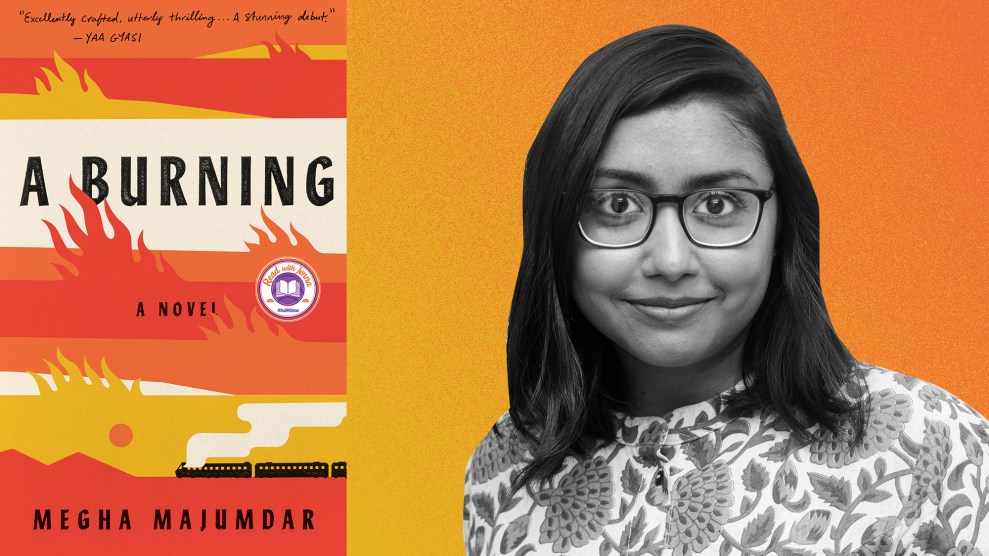

But soon enough, the tech titans began creeping into her ideas for a novel. In Vara’s The Immortal King Rao, out May 3 from W.W. Norton, society has splintered in two. On one side is the Shareholder Government, devoted to “Social Capital” and ruled by a master algorithm; on the other, the Blanklands, islands populated by anarchist Exes. King Rao has injected his granddaughter Athena with his memories. As she pieces together Rao’s rise, from son of a Dalit coconut farmer to global tech superstar, she, and we, must make sense of the price of technological conquest.

The book took 13 years for Vara to complete, a period during which she returned to journalism, writing for outlets like Wired and serving as the business editor for the New Yorker, and became a mother. In the meantime, Facebook ballooned into a global behemoth and morphed into Meta, and Elon Musk began trying to embed computer chips into our brains. In other words, though it waited more than a decade, the novel arrives at just the right time to help us make sense of this strange new world. I caught up with Vara in April to ask her about her inventive book and how her Dalit heritage worked its way into the story.

This interview has been condensed and lightly edited for clarity.

Your book examines what happens when tech leaders amass too much power. Elon Musk just offered to buy Twitter for $44 billion, potentially adding it to his growing collection of companies. I wondered what your reaction to that purchase is? [Editor’s note: Musk’s acquisition of the social media company now looks to be up in the air.]

I mean, it feels like a reminder that we think of ourselves as having these public institutions that help govern how society is run. But increasingly, a lot of what we do and where we live takes place outside of those institutions, like a lot of our communication takes place on Twitter. It’s a publicly traded company, but a private institution, you know, not a government institution. Which means it’s possible for an extremely rich man to come along and say, “I want to buy this.” It feels like people are sort of offended by it. But there are no structures set up to prevent something like that from happening. I think it’s a reminder to us of how how vulnerable we are to private individuals, and really wealthy individuals and wealthy corporations having a major role in determining how we do these basic things in life, including communicating with each other.

Your novel, in part, is a rags-to-riches tale about a character named King Rao, who climbs his way to tech superstardom. Where did you find the seeds for this story?

I was on a train with my dad and his wife in Peru, in 2009. I was in graduate school at the time, and I was trying to finish a collection of short stories. And my dad was teasing me, “Nobody reads those. What you should start is a novel.” Teasing him back, I was like, “Okay, Dad, what should I write a novel about then?” And he gave me two really bad ideas. And then he said, “You should write about my family coconut grove, where I grew up.” I had spent time there as a kid, when we visited India, and I’d heard stories about it from relatives—it did have a pretty dramatic history. My dad’s family were Dalit laborers on that land. And then they came to own that land, which came with a new phase of drama for the family. So there was this inherently interesting material.

But because I’d never grown up in the 1950s as a Dalit kid on a coconut grove, I felt poorly equipped to try to write a book from the perspective. At the time, my husband and I were watching the Battlestar Galactica reboot from the mid-2000s. And if you saw that you’ll remember there’s this technology, sort of like digital telepathy, that allows the access of what’s in other people’s minds. I thought if I could, as a writer, use a technology like that, then I would be able to write about this place and have a narrative voice that’s not claiming to actually embody a character growing up in that place. It started a little bit as a craft device.

At the same time, I was in graduate school after having spent three years as a tech reporter at the Wall Street Journal. I was hired to write mostly about Oracle; the beat was enterprise tech. We didn’t have anybody writing about Facebook at the time, so I ended up taking that on too, because I was the 23-year-old or whatever. I was spending time writing about and sometimes meeting Larry Ellison and Mark Zuckerberg, and finding myself pretty interested in how you get from being a 22-year-old kid who started this tech company to like, a 60-whatever-year-old man, however old Larry Ellison was, who’s one of the richest men in the world. That was all in the back of my mind when I went away to grad school; I didn’t think I was going to write about it. But then when I started to write about King and this technology, I just ended up writing my way toward this idea of King moving to the US in the 1970s and starting a tech company.

Then it took me 13 years to figure out what to do next.

Can you talk some more about your choice to make your main characters, the Raos, from the Dalit caste? What was your experience having ties to this caste? Especially given that you’ve lived mostly in Canada and the US?

It felt like my dad’s family story was inextricable from the story of caste. So it almost felt less like it was a choice and more that I was like, “All right, well, if I’m writing a story that’s like my dad’s story, that has to be an element of it.” I did not grow up identifying strongly as Dalit in particular. Growing up in Canada and the US in the ’80s and ’90s, caste oppression hadn’t been exported to the North America yet to the extent that it has been now just because the South Asian population in the US and Canada was smaller.

And then some point a couple of years ago, I spoke to this Dalit American who grew up in North America, like I did, named Thenmozhi Soundararajan. She’s a pretty prominent anti-caste-oppression activist. I asked her about the story behind how she identifies strongly as Dalit. And through that conversation, I remember realizing the usefulness of publicly identifying as Dalit so that emerging writers who may come from a Dalit background, or just other young people in the US from Dalit backgrounds, might see a visible person in the world, a journalist or writer from a Dalit background, and be like, okay that person is out there, you know what I mean? Because with caste, it’s different from some other aspects of racial identity, or ethnic identity, that are visible, you know? It’s easy to not identify publicly as Dalit. Nobody would necessarily know. So it felt like a helpful thing to make that known.

And secondarily, it felt important to acknowledge my own Dalit background in writing about Dalit characters. It’s not like I’ve grown up experiencing caste oppression on a regular basis, the way some members of my family growing up in India in the 20th century, or the way plenty of Dalit Indian American workers in the tech industry, for example, are facing discrimination. My experience has not been like that, which isn’t to say it doesn’t exist.

Did you spend time at your family’s coconut grove to do research? How exactly did it function?

I visited as a child just a small handful of times. Then in 2010, after finishing grad school, I went and spent a month in India, and spent several days back on the coconut grove, walking around and taking notes and talking to family members. It was kind of like in the book: At first they were just growing their own coconuts and selling them. And then they were like, “Oh, we can do better business if we just buy coconuts from all the other farms, and then process them on our land.” They would dry them and process them on their own. The business started to be a little less reliant on the actual coconuts and more on like, the middleman role.

I also met with scholars who studied Dalit life in the 20th century in South India, and how it evolved over time, and I talked to somebody at the Coconut Research Station. I did approach it a little bit with my journalist hat on, too.

One character describes how every part of the coconut plant is useful, from the palm leaves to the coconut’s shell. There’s kind of a parallel, I thought, in how King tells his granddaughter Athena, “You and I—we Raos—don’t believe there’s a problem that doesn’t have a solution!” It seems like this is an apt fruit to represent their family. And yet, it seemed to me that the novel was examining the limitations of this solutionist mindset. Do you remember one of the first times you questioned whether technology was going to solve our problems? Or whether technology was really making things better?

It’s a great question, but I don’t think I have a good answer. The idea of tech solutionism that comes up when King and Margie start the company, I was thinking about that a lot. We think of solutionism as being this sort of new concept inherent to the past 20 or 30 years of the development of technology, but it’s also in some ways just a very human orientation, right? Like the way in which we, as a species, are always trying to figure out what we can wring from the world.

I noticed there were two main post-capitalist models portrayed in the book. One was the shareholder government that was corporate-run and dictated by a Master Algorithm. And then shareholders sell their labor at will and are compensated in social capital. This to me sounds like, what would happen if we allowed Mark Zuckerberg and Elon Musk to design our government?

Yeah, I mean, yes [laughs]. I was saying something to my mom about the relationship between my novel and the real world. And she was like, “Yeah, but your novel’s fictional? It’s just about like, what would happen if you know, somebody took this too far?” And I said to her, like, “Well, yes. And it’s totally easy to imagine, like the actual tech CEOs that currently exist in our world, potentially taking the world in that direction.” It doesn’t feel like too much of an imaginative stretch, right?

Yeah, unfortunately it does not. So in the other model, some people that you’ve deemed “Exes,” they’ve kind of abandoned their role as shareholders and fled to the Blanklands. They do a lot of bartering and contributing to the community for the good of the whole. (This is kind of a side note, but I was interested to see that sex work, as the oldest profession in the world, still maintains an important role in both economies.) So I was wondering to what extent these two models were based off theories by real economists and philosophers.

They were. I read a lot while trying to construct both scenarios. I read Thomas Piketty’s Capital and Ideology, which talks about caste. That book is trying to understand a lot of things, including what the future of government could look like in the context of the way in which our economies are changing. And then I also read these classic anarchist writers and thinkers, like Emma Goldman’s autobiography. I wanted both of those models to be informed by a real enough understanding of how those systems could play out. But I wanted the book to make clear that they each have their limitations, too, right?

I mean, neither of them end up feeling like great places to be. But if you did have to choose, which society would you want to be part of when Elon Musk takes over and starts running everything by algorithm?

I love the question. But I don’t want to answer it for readers because I want the book to leave it open-ended.

That’s fair. A press release summed your book up as posing this urgent question: “Can anyone—peasant laborers, convention-destroying entrepreneurs, radical anarchists, social-media followers—ever get free?” And so I wondered, when do you feel the most free these days?

Probably when I’m in my own small world with my immediate family and our own little community and, you know—not online.