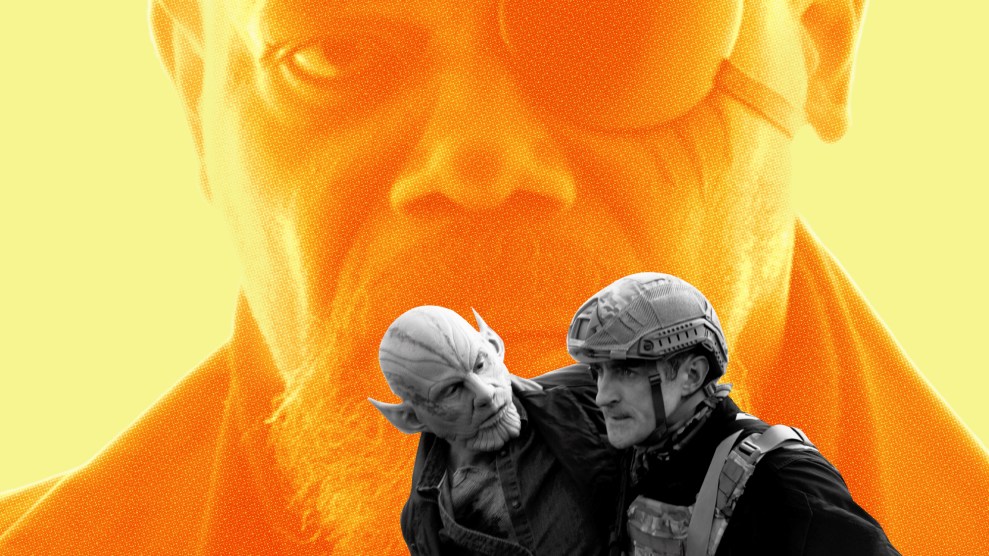

Mother Jones illustration; Disney

Secret Invasion, Marvel Studios’ new six-part miniseries, was supposed to be the Marvel Cinematic Universe’s answer to the Star Wars series Andor: a political spy thriller filled with intrigue, focused on the murkier sides of a large, interconnected universe. Instead, Secret Invasion is emblematic of—and yet another vehicle for—Marvel Studios’ empty political commentary. Through its ups and downs, I love the MCU, but its take on refugees and xenophobia is unsurprising.

After watching all six episodes of one of the dullest Marvel offerings to date, I was left mortified by its representation of the Skrulls: introduced sympathetically in 2019’s Captain Marvel as shape-shifting refugees looking for a new home, the Skrulls are now portrayed as disillusioned, spiteful radicals seeking to make Earth that home—by starting a world war.

Led by a Skrull called Gravik, an extremist faction pursues nuclear war after master spy and Avengers founder Nick Fury (Samuel L. Jackson, famously) fails to follow through on a promise to find them a permanent refuge. It’s an admirable direction for the show, which seeks to humanize the mysterious and captivating Fury, flaws and all. Instead, Secret Invasion not only reveals that Fury is a chump, but that he’s actively exploited the refugees for his gain, failing to meaningfully help the Skrulls despite their decades of service as his spies on Earth (But guys, he feels really bad about it.)

If the writers hadn’t made Gravik a genocidal maniac with daddy issues, you’d forgive me for siding with him—and that’s the problem. Gravik is presented as a man whose people live in destitution, his labor exploited by the state since childhood under the false promise of a place to live. He’s supposed to be the bad guy.

The MCU likes villains with compelling social critiques—sympathetic motives, twisted methods. Black Panther villain Killmonger seeks global Black liberation but is a violent misogynist whose quest to “arm oppressed people” is driven by personal revenge. He’s stopped, funnily enough, when Chadwick Boseman’s King T’Challa teams with the literal CIA to overthrow Wakanda’s legitimate ruler. In Avengers: Infinity War and Endgame, Thanos wants to save the universe from ecological devastation—by erasing half its life. Falcon and the Winter Soldier’s anti-authoritarian Flag Smashers desire the borderless world that emerges after Thanos snaps half the universe into dust, but resort to violence, killing civilians (bad) and robbing banks (Less bad. Fuck banks.) These characters reflect societal fears—shouldn’t there be global equity? Sustainability?—and invariably link them to brutal extremism, delegitimizing their core beliefs. It’s a consistent narrative choice that not only simplifies complex issues but perpetuates the notion that radical change, however urgent, is inherently too dangerous to try. By consistently aligning radicalism with villainy, the MCU draws viewers back towards status-quo centrism, building a soothing world where being a hero means protecting the established order.

If we dismiss these narratives as mere entertainment, we’re overlooking media’s power to shape social and political consciousness. With 32 movies, nine TV shows, and more than $30 billion generated at the box office, the MCU is one of the biggest media franchises in the world. In an age of misinformation and hidden agendas, media literacy is paramount, and it’s essential to hold global corporations accountable for the messages they convey.

Marvel products “pervade our lives and become a starting point for conversations about misogyny, racism,” explains Nicholas Carnes, a Duke University public policy professor and co-editor with Carroll University political scientist Lilly Goren of The Politics of the Marvel Cinematic Universe. “These are such enormous cultural artifacts,” Carnes says. “We can talk about any big political issue, there’s a good chance we’ve seen it in a substantial way in the MCU.”

When MCU villains mount radical attacks on unjust systems, the heroes typically aim to restore a sense of normalcy, not address the root causes of issues raised. At first, Black Panther brilliantly subverts this: T’Challa admits that Killmonger is right, confronting his ancestors for maintaining the isolationist policies of Wakanda, the world’s most powerful and technologically advanced nation. But Marvel heroes’ vague, incremental fixes again reinforce the status quo. With Killmonger and his revolution dead, T’Challa’s grand gesture against Black poverty and inequality is to open an outreach center in Oakland. Change in the MCU, as Noah Berlatsky wrote in 2019 for the Verge, “comes about not through community action or political efforts, but through the outsize actions of special, strong saviors.”

Sam Wilson, hero of the 2021 Marvel series The Falcon and the Winter Soldier, is moved by the Flag Smashers’ cause and offers a solution: a stern speech urging world leaders to “do better.” None of the heroes in Avengers: Infinity War or Endgame rebut Thanos with any ideas whatsoever on using the infinite powers of the Infinity Stones to better serve the universe. Hell, Iron Man’s plan for global peacekeeping involves militarized, automated robot police and not, uh, you know, doing ANYTHING with the Arc Reactor, established in-universe as another infinite power source. (The man discovers how to time-travel, by the way.)

A theme emerges: while the world has its flaws, drastic changes are just too perilous, and it’s better to return to what’s familiar. “It’s not an accident,” Carnes says, “that the most popular villains and stories are when the MCU is giving us a way to think through those social anxieties.” In other words, this isn’t a bug, but a feature—and not just in Marvel’s work. Superhero stories have been political—within status-quo bounds—since the early days of Captain America beating the absolute piss out of Nazis. Carnes calls these stories a way for “people to cope with reality.”

In today’s superhero media, there’s even superficial anti-capitalism. But corporate self-deprecation is nothing new (see: Black Mirror’s “Joan is Awful”) and always serves a purpose. Spider-Man: Far From Home‘s Mysterio leads a group of embittered, mistreated Stark Industries workers who want to steal Tony Stark’s orbital defense grid and unseat him as Earth’s most prominent superhero. Anyone can relate to their workplace mistreating them and stealing their credit. Meanwhile, Marvel was doing just that to its visual effects workers—and had been for years.

For Marvel and its parent company, Disney, narratives enriched with co-opted radicalism offer a cultural and commercial edge. They tap into contemporary discourse, making their films and shows appear timely and relevant without having to say anything truly meaningful. That not only attracts a broader audience, it gets out in front of common critiques and sparks discussions, ensuring that their content remains at the forefront of pop culture.

“I actually think that’s the key to their success,” Carnes says. “We can sit here and have a conversation: ‘Was Gravik right? Was Killmonger?’ I think that’s a big part of why this universe does so well.”

It’s not malice on the part of MCU writers or showrunners. It’s a manifestation of capitalist realism in entertainment. As Goren told me, there are different writers on every project, with little direct oversight by top Marvel bosses. But production and profitability pressures, and the need to maintain mass appeal, bend storytelling to fit the constraints of the prevailing socioeconomic system. (George Lucas famously said Soviet directors had more creative freedom than he did in Hollywood, where “you cannot lose money…you’re forced to make a particular kind of movie.”) As Mark Fisher wrote in his 2009 book of the same name, capitalist realism discourages envisioning, let alone implementing, alternatives to the status quo, and this mindset inevitably seeps into creative works. That’s why Black Panther—even though it’s a solid, imaginative film that made huge strides in the cultural representation of Black people on screen—has King T’Challa opening cultural centers in Oakland instead of using his country’s vast wealth and technology to achieve Black liberation.

Not all superhero fiction has to be this way—not even Marvel’s. The 2018 comic book series Immortal Hulk, written by Al Ewing and inked by Joe Bennett, offers a compelling inversion of capitalist realism. Through its exploration of Marvel’s Hulk as a symbol of transformation and resistance against oppressive forces, the series challenges the notion that status-quo alternatives are unattainable. After Bruce Banner’s mind is split, with his human self and multiple Hulks fighting for control, a new Hulk—the “Devil Hulk”—decides that human society, with our greed, warmongering, and environmental destruction, needs to be destroyed. This Hulk wants to literally smash capitalism. An unapologetically anti-capitalist work of art, Immortal Hulk exemplifies how comics (and even the MCU) could offer counter-narratives, urging audiences to question prevailing norms and consider the potential for collective change.

“Together,” Hulk says in one issue, “We’re the strongest there is.”