Mother Jones illustration; Billie Woods; Getty

I became reacquainted with Raffi in the spring of 2020, around my son’s first birthday. These were the early days of the pandemic: People had barely stopped hoarding toilet paper; we’d started going to the car wash for fun. It was on one of these drives that I first burst into tears to Raffi’s “All I Really Need.” Ostensibly, I was playing the track for my baby, who was babbling in his car seat behind me as I drove through eerily quiet San Francisco, trying to forget Trump had just suggested we all drink bleach. The lyrics were a balm for my frayed nerves: All I really need is a song in my heart, food in my belly, and love in my family…

Raffi Cavoukian, should you need a refresher, is a widely beloved Canadian children’s singer with a deep, kind voice. He’s sold more than 15 million records during his nearly 50-year career, but he’s best known for his hits from the ’80s and early ’90s: “Baby Beluga,” “Down by the Bay,” and “Bananaphone.” Before the advent of streaming services birthed a thousand on-demand entertainment options aimed at young children, Raffi was—and for many of us adults who grew up with his music, known as “Beluga grads,” still is—a superstar. He inhabited the same stratosphere as Mr. Rogers: a calming, nearly hypnotic, and constant presence in our living rooms and inner worlds.

Though he’s faded a bit from the limelight, Raffi, now 75, has never stopped making music; his 24th album, Penny Penguin, dropped April 19. In the last three decades he’s also become a vocal climate activist, performed for Nelson Mandela and the Dalai Lama, rejected an offer to make ungodly sums of money with a Baby Beluga movie from the producers of Shrek, and established the Raffi Foundation for Child Honouring, a nonprofit organized around the singer’s “children-first” vision of sustainability. You can read about all this and more in his memoir, one of three books he’s published for adults.

But the best way to learn about Raffi’s movements (as I learned in the spring of 2020 after wondering, through tears, “What has that guy been up to?”) is to follow him on Twitter. There, he maintains perhaps the most earnest, sweetly radical feed in the history of the internet.

A typical Raffi Twitter day in 2024 includes dismay at the 1 percent (“don’t need no billionaires / need to breathe clean air”) and the right-wing legislators who enable them (#fascists); calls for a ceasefire in Gaza; a Wordle score; a retweet of a climate expert; some pop culture opinions (he’s a Swiftie, and he loved Barbie); quotes about the importance of nurturing children; descriptions of his healthy dinners; and commentary on whatever hockey game he’s watching (sometimes in poem form). The cumulative effect is charming, occasionally hilarious, and—in a sea of painstakingly curated celebrity political statements so vague and careful they fail to say anything—incredibly refreshing.

Ahead of the release of Penny Penguin, Raffi’s first real record in five years, I spoke to the musician over Zoom from his home on Salt Spring Island in British Columbia. Our conversation has been lightly edited and condensed.

Your new record, Penny Penguin, is a collaboration with the group Good Lovelies. What were its inspirations?

I was watching a Netflix series, Atypical, about a family with a 16-year-old boy on the autism spectrum, and his great love was penguins, especially in Antarctica. He would always be on about this penguin in this aquarium he would go to—drawing penguins, everything. That kind of stayed with me. Fabulous series, by the way.

Other songs, like “My Forest Friend,” I wrote for my forest that I live with. I live on a few acres of land, and no matter what, this forest keeps on going. Its roots are deeply embedded in the ground. Even though the island I live on is a rock, so the root system has to go horizontal! I mean, the forest finds a way.

Then about a year ago, I met this wonderful musical trio in Toronto named the Good Lovelies—three women in their 40s, all Beluga Grads. They were doing a house concert near where I live. I was in the first row and I was knocked out. And apparently they were knocked out that I was there. We struck up a friendship very quickly, and I asked them to sing on a few songs. I wound up being so taken with their creativity and their work ethic that they ended up singing on 10 out of the 14 songs on the album.

Your music was such a ubiquitous part of childhood for so many people—I don’t remember a time before I knew your songs. Do you recall your earliest awareness of music?

This would have been in my Armenian family home in Cairo, Egypt, where I was born and grew up, and I remember, to this day, the songs from pop radio at that time—the early 1950s—that I used to hear on my parents’ stereo. When I came to Canada at the age of 10, I had to learn songs like “Baa Baa Black Sheep” word for word, because they weren’t part of my growing up. I think that’s sort of interesting, this outsider’s sense of discovery.

In terms of vocal songs, that would have been my mother singing me lullabies. And my father was a great accordionist and a fabulous singer; he and I used to sing in the Armenian church choir in Toronto for years. He was something.

Your parents landed in Egypt after fleeing the Armenian genocide during World War I. Were you aware of what that meant, growing up, that you came from people who had been persecuted? Were there conversations in your house about it, or was it sort of just in the water?

A little of both. My mother’s often-repeated phrase was “How we suffered.” And when she said that she was echoing her parents as well. I do think it’s partly what makes me such a passionate defender of democracy—you see me on social media writing “fight fascism.” I believe it’s everybody’s duty. I mean, you’ve heard it said “Democracy is not a spectator sport.” I think it’s the duty of every citizen to fight fascism, because our ancestors fought in wars and died defending liberty. The least we can do is defend the democracies that others gave their lives trying to protect.

Your career spans so many social justice movements—civil rights, the anti–Vietnam War movement. Are you surprised by where we’re at right now politically?

I’m shocked. Especially at the [rollback] of women’s rights in your country. But I also remember that we’ve always lived in troubled times. You can go back millennia, and the spiritual and political heroes that inspire us lived in very difficult times. It’s not like they waited for things to get okay, and then they did their thing, right? You can think of Jesus, Gandhi, Martin Luther King. These people, they responded with their entire being, their whole humanity. And that’s what we are called to do—to be fully human, to be eyes wide open to what’s happening.

Are you a spiritual person?

Sure. In the sense that I know that we are spiritual beings in human form. Because I remember, when my grandma passed away, looking at her body in the casket, knowing that it wasn’t grandma, it was just her body. That was an early signal to me that we are the spirit, the life force, that animates the body. It’s all magic, of course. Including spinning on the third planet from the sun, and there’s gravity, and we don’t fall off. The whole thing is magic.

Our task is to learn about the magic and how to navigate it. It helps if we remember that our spirit is essentially love. So the learning in the school of life is how to galvanize that love that we’re born with into a positive force. But the thing is, for every infant, that inborn love needs affirming from the outside. A caregiver needs to hold a mirror that affirms and gives a sense of purpose to a child’s innate love. That’s why it’s so critically important that we as children feel seen and respected for who we feel we are.

You seem to be deeply in touch with who you were and what you needed as a small child. Why do you think that is?

A lot of therapy! [Laughs.] In my late 30s, it became clear to me that I needed to do some emotional growth work, and I was lucky enough to be with one or two very skilled therapists, and they helped me to address many of the challenges that I had. In my early childhood, growing up in a fairly authoritarian family, my parents loved me greatly. But it was at times a coercive love, not exactly a respectful love. And I felt sometimes like a possession. So there was a lot I had to work out.

I’m really glad I did it, because I learned a tremendous amount not only about myself, but about how it works with humans, that the love we are born with is dependent on caregivers and their respect and love for us. As author Jean Liedloff said in her book The Continuum Concept, the young of the human animal has a need to feel right, good, and welcome in the world. And when you don’t feel that way as a youngster, that’s when the false self arises, because you need the external love so badly, you do anything to get it. Therapists tell me this is how it works.

Let’s talk social media: You were vocal about its dangers, especially for young people, in your 2013 book, Lightweb Darkweb: Three Reasons to Reform Social Media Before It Re-Forms Us. But you clearly enjoy it, and you’re a regular Twitter user. What’s your social media diet like these days? Is it the first thing you do in the morning?

The first thing I do is usually Wordle. [Laughs.] It just awakens the mind, you know? But really, on social media, I’m defending democracy, first and foremost. Expressing my utter sadness at what’s happening in the Middle East and in Ukraine. Solidarity with all victims. Like I said, we’ve always lived in troubled times. You can point to various hotspots around the world—there’s been a civil war in Syria going on for 13 years. I mean, you can go crazy trying to keep up with everything that’s going on in the world, right?

What you can do is try to learn, and find ways to be in solidarity with the innocents of our world. And to me, that means children, because they’re the most innocent in any conflict. They did nothing to bring on any of it. So my heart goes out primarily to the innocents. And then that way I find my bearing.

Since October, it’s been interesting to watch celebrities assess if, how, and when to speak out about the Middle East, doing this dance of “What’s the most prudent position to take?” I think you were one of the first public figures I saw clearly criticizing the actions of the Israeli government and calling for a ceasefire. I’m curious where you think that sense of freedom comes from.

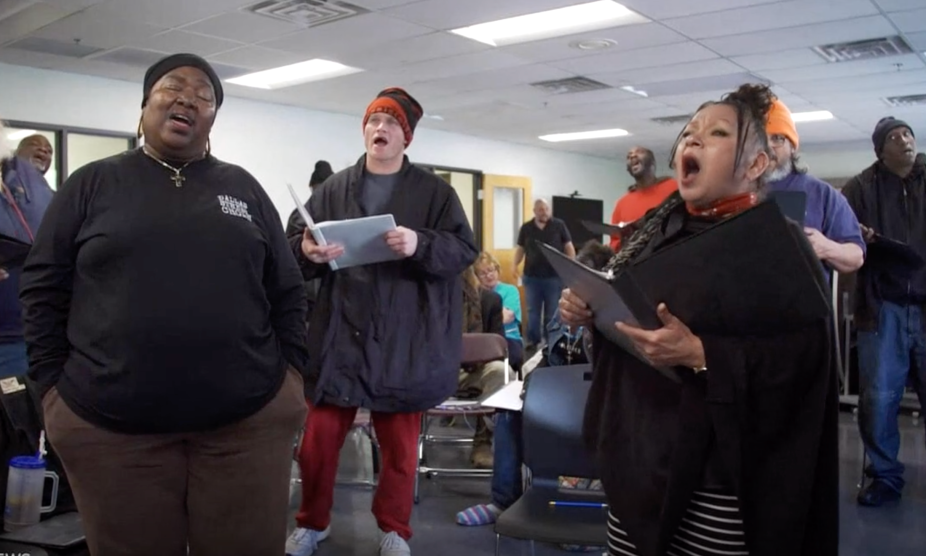

Well, I thought we lived in free countries! Each one of us has both a duty and an opportunity to speak out. Of course you try to be as sensitive as possible. In terms of what’s happening between Israelis and Palestinians, I was lucky enough to have written a song called “Salaam Shalom” back in 2004. If you search that song, you’ll see me singing it with a 300-voice choir. Back in 2004, I was saying: “Sing a new song. Walk a new path. Make a circle where we all belong.”

I’m very fortunate to have some Jewish friends who are among the most progressive voices who, with great compassion, want to see an area that is secure and in the healthy bonds of coexistence. At some point two sides or more have to sit down and forge a pathway of new peace. There is no other solution. So our hearts break. Our tears fall. But we have to keep in mind the lasting peace that we all seek.

I have to ask about the controversy with the 17th-century Armenian rug that you posted on Instagram in December, which upset some people because it had swastikas in its pattern. You apologized and deleted the post.

There’s nothing much to say. I posted a rug in all good faith, and I was showing a thing of beauty from my Armenian heritage. A 17th-century rug with a symbol that the Nazis took and distorted. It used to be a fertility symbol, from what I know, representing four seasons. I mean, for anyone to think that I, in any way, after writing “Salaam Shalom,” would be presenting something injurious would just be wrong. So that’s why I deleted it. I didn’t want any misunderstanding.

When you’re on Twitter calling Trump a fascist, has there ever been a moment where you thought, ‘Oh, I’m reducing my fan base by a bit’?

Not at all. When the stakes are this high, you have to call it as you see it. There was never a person more unfit to be in the highest office of the land. He was a Putin puppet. He still is. He’s a threat, and I think more and more people see him for who he is. And that leads me to think that if the voting public shows up in great numbers that democracy will stand. And that’s our challenge. That’s our duty. Every single person who reads this article, I urge you, I exhort you to vote. Do your duty as a citizen and vote democracy.

What do you say to people who are frustrated by the limitations there? I know so many young people who feel disappointed and angry, heading into this presidential election, that these are our choices.

I say vote, and also run for office. Widen the choices. Press for a more democratic Democratic Party. In Canada, we work hard towards proportional representation. That still eludes us, but we work hard. The right things are worth fighting for. It’s always been that way. I grew up in the civil rights movement. “This Little Light of Mine” was a civil rights song. So, let it shine, baby. We just need caring souls.

I think what so many people are grappling with is this feeling of cynicism and helplessness. You know, I’ve been voting my whole life, I’ve been to lots of protests. Roe v. Wade was still overturned.

Exactly. But we also have a lot of information as to why it was overturned, how decades of funding from the extreme right wingers caused the democratic norms to slide—even going to Citizens United, the Supreme Court decision to give corporations a power they should never have. So you become educated. And when you see that things have developed for decades to shape current negative events, then you also understand that it may take decades to undo that. But that’s okay, because that’s your duty. It’s not, “I’m going to give this six months and then I’m going to pass.” No, you can’t. You have to remain engaged in democracy as long as it takes.

I’m curious how you balance staying engaged with current events, especially these devastating, violent conflicts—and then put the phone down and write a song about a penguin, and think about bringing joy to children and families.

Well, my songs have often been inspired by the beauty of the natural world, including the animal kingdom. And I’m so lucky that I have the creative capacity, in music making and specifically songwriting, to help me feel like I’m practicing the magic of inspiring and delighting. I’m also sustained by the truths that I know in my life. Essentially, we are love. And from that love comes responsibilities, including kindness.

Whenever I remember that love exists, that children exist—and they are, as Leonard Cohen wrote in his beautiful song “Suzanne”: There are children in the morning / they are leaning out for love and they will lean that way forever. How can I not be there for those children? How can any of us not be there? They need us.