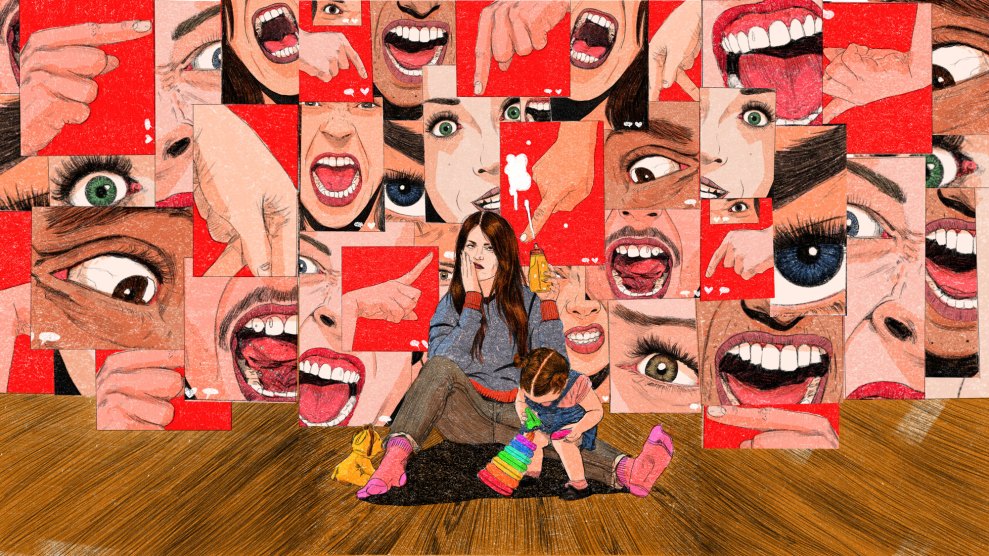

Clockwise from left: Zoe Saldaña, Jenna Ortega, and Alfonso CuarónMother Jones illustration; Netflix; Warner Bros. Pictures; Valerie Macon/AFP/Getty; Getty

“I was like, ‘Oh, my God, look at her. She’s like me; she speaks Spanish, and she has an accent like my mom.’” That’s how Mathia Vargas describes the first time she remembers seeing a Latina in an American movie: Salma Hayek in the 1997 romantic comedy Fools Rush In. “I grew up, and we’d look nothing alike, but at the time, I was like: There’s people that look like me in [an] American, English-language film.” Vargas is a Dominican American actress from New York who—like many Latino movie and TV lovers—didn’t often see people like herself on screen growing up. More than two decades later, that’s still the case.

According to research by consultancy firm McKinsey & Company released last year, which looked at movies and shows released from 2013 to 2022, Latinos held 4 percent of lead roles in theatrical films and television shows, and 7 percent on streaming series, despite making up 19 percent of the US population. That makes Latinos one of the most underrepresented groups in Hollywood; only Native American representation is similarly bad.

Vargas says she fell in love with acting when she was a little girl: “I moved back to the States when I was 3, and I learned English watching Sesame Street and Barney, and I always wanted to be a kid on TV.” But outside of those shows, Vargas says, she “rarely saw kids that looked like me, so I never really thought it was a thing I could do.” Still, she never let go of her dream: She became a premed student and minored in theater before deciding to pursue acting as a career.

The challenge ahead of her was clear from the beginning. She recalls a meeting with a manager early in her career—who she described as great—whose office had a wall of shows casting in New York, with every actor who could be the right fit: “I look across this wall,” Vargas says, “and there’s not one person that looks like me up there.”

This lack of opportunity for Latinos in the industry isn’t limited to on-screen roles; it extends to behind-the-scenes talent as well.

Films were half as likely to revolve around crime when Latinos had significant behind-the-scenes roles.

The same McKinsey study also found that 5 percent of theatrical film directors and 1 percent of broadcast and cable TV showrunners, the most senior position on television shows, were Latino. The consequences extend not only to the career prospects of Latino directors, but also to the types of stories about the Latino community that make it on screen. Hiring Latino talent off screen, the study found, leads to fewer stereotypical stories about the Latino community and to more nuanced depictions of the diverse groups that make up that community: Films were half as likely to revolve around crime when Latinos had significant behind-the-scenes roles like producer, director, or writer and 3.5 times more likely to revolve around family. “Latino directors understand that where you come from, your ethnic background and your culture,” Vargas says, “influences how your character expresses themselves and walks through the world.”

And while opportunities for Latino talent are limited, those films Latinos lead or direct are more likely to be nominated for an Academy Award or Golden Globe and more likely to win an award once nominated, according to the study. Recent examples include Ana de Armas’ best actress Oscar nomination for her role as Marilyn Monroe in Blonde and Colman Domingo, who became the first Afro Latino nominee for best actor for his portrayal of activist Bayard Rustin in 2023’s Rustin. Guillermo del Toro and Alfonso Cuarón have both won the award for best director, in Cuarón’s case for the beautiful black-and-white 2018 film Roma, telling the story of an Indigenous live-in housekeeper in Mexico City.

The crowning irony: Despite the fact that Latinos are underrepresented on screen, they are actually overrepresented when it comes to spending on movies and TV.

The two biggest movies of 2024 were Pixar’s Inside Out 2 and Marvel’s Deadpool & Wolverine, both produced by Disney subsidiaries. Both made over $1 billion at the box office, and if you looked into the crowds on opening weekend, you would see a disproportionately high number of Latinos. Despite making up just under a fifth of the population, Latinos were about a third of Deadpool & Wolverine’s opening weekend audience and nearly 40 percent of Inside Out 2’s.

And that’s the rule, not the exception. The McKinsey study found that Latinos had the highest per-capita spending at cinemas of any demographic, watching an average of 3.3 movies a year in theaters compared with 2.3 for white audiences. Latinos also account for 24 percent of streaming subscriptions. And the study found that Latinos didn’t just spend more, but also that movies featuring Latino talent made more money.

Last year, Beetlejuice Beetlejuice had the second-highest September domestic debut in history at $110 million and outgrossed the original Beetlejuice’s total worldwide box office returns. The movie went on to become the sixth-highest-grossing film of 2024 in the United States, with Jenna Ortega in a lead role coming off her massive Netflix show Wednesday. The McKinsey study found that movies with Latinos as directors or producers or in lead roles, like Beetlejuice Beetlejuice, made 58 percent more money at the global box office. Other recent box office successes with Latino leads include the last two Scream movies, led by Melissa Barrera, and Avatar: The Way of Water, led by Zoe Saldaña—who won a Golden Globe and is nominated for an Oscar this year for her role in Emilia Pérez and became the first actor in history to appear in four movies that grossed over $2 billion. Camilo Becdach was one of the researchers behind the McKinsey study, which estimated that the US film and TV industry could add $12 billion to $18 billion to its roughly $180 billion annual take if it improved Latino representation, and says it “isn’t just that more Latinos are showing up, it’s that all groups are showing up.”

Vargas says she’s seen improvements in the types of roles now offered to Latinas compared to when she started her career more than a decade ago. “It was rough, because I could get a sense of what they were looking for: Latinas to be sexy, to be sassy. There wasn’t a lot of room for nuance there.”

Now, Vargas says, “there’s a little bit less of that stereotypical Latina. I’m auditioning to play lawyers. I’m auditioning to play entrepreneurs and romantic leads that don’t feel like they’re steeped in stereotype.” She partially credits that improvement to an increase in the number of “open ethnicity” roles, which allow anyone to audition, but still thinks there aren’t enough opportunities for Latinos, and Afro Latinos in particular. “I’m rooting for everybody with a vowel [at] the end of their last name, but I’m not seeing enough improvement in terms of folks who make up the global majority and are darker-skinned or Indigenous.”

“The problem is not that [non-Latinos] are playing Latinos. The problem is that Latinos are not playing anything.”

Pablo Andrade is an actor from Venezuela working in New York and executive director of the Hispanic Organization of Latin Actors, which works to expand the presence of Hispanic and Latino artists in the entertainment industry. “It’s hard for the general audience to understand that our community is so diverse,” he says. “We have Afro Latinos. We have blond Latinos. We have Latinos from all over America and all other places. For many casting directors, a Latino looks like this, sounds like this—and they are not going to find those Latinos that they have in mind everywhere.”

Andrade says his accent has been a major barrier to landing movie roles, which led him to focus on theater, and points out how Hollywood sometimes misses obvious opportunities to hire Latinos, citing the recent controversial casting of James Franco as Fidel Castro in the yet-to-be-released Alina of Cuba as an example. “Our community was enraged,” Andrade says. “If we had 20 percent of the roles in Hollywood—that guy’s a fantastic actor. Give it a try. A Latino could be played by anyone. But the problem is not that they are playing Latinos. The problem is that Latinos are not playing anything.” The film’s producers, that is, could have given a Cuban actor the opportunity to progress in their career instead of going with Palo Alto Fidel Castro.

Hiring more Latinos, based on the study’s results, would likely net more money for an industry that has struggled to bring revenue back to pre-pandemic levels and yield better stories for us to watch. But convincing studios of that is a challenge. Becdach sees many reasons. One is that studios often determine whether they are willing to fund a movie based on “comps,” other projects that they can point to as comparable to the one being pitched. That presents a challenge for Latino creatives: They have fewer projects to point to because fewer Latino-led projects have been greenlit in the past. As one Latino animator interviewed for the study put it: “It’s the chicken-and-the-egg problem: Because there are no hits, they don’t want to make Latino movies. And because they don’t make Latino movies, there are no hits.”

The other major challenge for Latino creatives is that, perhaps more than any other industry, the film and TV business relies on people hiring those they know. One non-Latino executive interviewed for the study said: “There are no applications for production jobs…A studio head hires division heads, and the division heads hire other people [they] know, and this cycle perpetuates—and as a result, Latinos don’t get hired.” Entry-level positions are often given to those with university or family connections in the industry, which many Latinos lack. One possible solution is to have more Latinos in creative leadership positions; the study found that when Latinos are in these roles, they are 15 times more likely to hire Latinos than are their white counterparts. “When you have [a] Latino producer [or] director, you’ll see greater representation on screen,” Becdach says. But that’s another Catch-22, because studios have to first be willing to hire Latinos into those positions. Becdach says Hollywood studios should be thinking of ways to create a pipeline for Latino talent to network and receive mentoring so that more can eventually get into leadership positions.

As with any creative endeavor, mistakes are going to happen; not every movie or TV show will accurately represent every Latino group, and not every story featuring Latinos will be great, but more opportunities will mean more and better stories. “I know it’s hard to get it right,” Vargas says. “But we just want to be in there. Let us be the good guys, the bad guys, maybe less of the bad guys. I would like to see quantity and quality.”