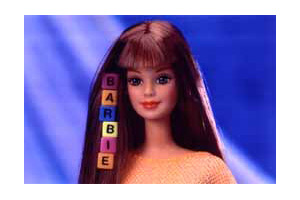

So Barbie — the classic white, blond standard-bearer of fake beauty — is getting a new shape. That’s welcome news for those of us who have long lamented the exaggerated hourglass figure (to be polite) of one of the most popular women in America. But it’s not all good news in Plasticland. While Barbie’s trademark nipple-less, mountainous, hard-plastic breasts are being cut down to size and that itty-bitty waist is getting bigger, her hips are also set to slim down with the new model, making her not so much more healthy and realistic as simply pubescent.

Translating Barbie’s plastic proportions into human being terms is a favorite pastime of eating disorder activists and other anti-Barbie crusaders; estimates have put the doll’s life-size bust between 38 and 40 inches, her waist at 18-24 inches, and her height between five and a half and an outlandish more than seven feet, with a weight of 110 pounds. Need some help visualizing that? Imagine Anna Nicole Smith’s breasts, suspended above Kate Moss’ waist (after a fast) all resting comfortably on Cheryl Miller’s frame (after a mid-life growth spurt).

Why is Mattel remolding Barbie? Her manufacturer says that complaints about Barbie’s unrealistic proportions have nothing to do with it. “Our intention is for her to have more of a teenage physique,” says Mattel spokesperson Lisa McKendall. “In order for hip-huggers [the new doll’s debut outfit] to look right, Barbie needs to be more like a teen’s body. The fashions teens wear now don’t fit properly on our current sculpting.”

The question of how many teen bodies “look right” in hip-huggers didn’t seem to occur to Mattel. When asked if younger girls would identify more with Barbie’s new teen-like body, McKendall replied only that the “reality of fashion” was dictating the change.

Mattel isn’t remodeling Barbie out of a sudden recognition that young girls might learn some false lessons from her absurd proportions, or out of contrition for years of pretending that Barbie doesn’t have the cultural effect that so many people believe she does. Nope; they’re doing it because Barbie’s big bustline is outdated. If you don’t count porn and “Baywatch”, there’s not a lot of call for the 38-18-24 look right now. Slim-hipped, perpetually adolescent bodies, though — we got plenty: Heroin chic may be on the way out, but its I-haven’t-eaten-since-1987 legacy lingers on. Fashion, in clothing and bodies, has passed Barbie by. Now she’s racing to keep up. If consumers want to believe that Mattel cares about the emotional health of American women, well, that’s just icing on the marketing plan.

Ruby

Ruby

At the opposite end of the spectrum from Barbie, new or old, is Ruby, a pudgy doll featured in ads and posters for The Body Shop, which has long sought to use self-esteem as a selling point. The Ruby ad, which has appeared on posters and magazines including the current issue of Mother Jones reads, “There are 3 billion women who don’t look like supermodels and only 8 who do. Love your body”. [Editor’s note: Body Shop CEO Anita Roddick is a board member of, and contributor to, The Foundation for National Progress, the parent organization of Mother Jones and the MoJo Wire.] “Ruby started as humor, teasing traditional notions of how women are presented,” says spokesperson Paulette Cleghorn. And clearly, women are looking for a tweak of the skin and bones look that’s everywhere these days. “We’ve had a huge response — positive, positive, positive –to Ruby,” says Cleghorn. So much so that the Body Shop is considering manufacturing Ruby, who so far has appeared only in print.

What does Mattel think of Ruby? “Yes, I’m familiar with it,” says McKendall. Any comment? “No. But our legal department is looking into it from a trademark perspective.”

Barbie’s negative effects on women’s feelings about their bodies are a well-worn cliché — but, like so many clichés, this one has a truth at its heart. Barbie may not be the cause of eating disorders and body hatred, but her universally recognizable profile makes her a flashpoint, an image of female perfection, a symbol of the drawbacks of any such images, and a convenient scapegoat for our cultural troubles with them. Regardless of Mattel’s stated motivation for the new body, the new doll won’t be any more positive for women than the old.

Barbie’s exact new proportions, which Mattel is keeping secret until she is released, will doubtless be translated into human pounds and inches for further “can you believe it” rhetoric. But it barely matters whether those measurements will be attainable by average girls. Clothing fashion is dictating Barbie’s shape. Which makes the point once more that in our market-driven world, women’s very flesh, not just their clothes, is subject to cultural whim. Women still try to reshape their bodies for clothing. It won’t be the other way around until we stop expecting dolls–skinny and busty or proportionally size 16 — to set an example.

Lisa Jervis is the editor of Bitch: Feminist Response to Pop Culture, an uppity little ‘zine printed on pulped trees.