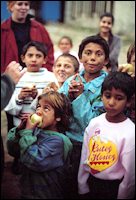

Image: Zoran Mircetic

The bleak structure, home to about 130 other Roma — or Gypsies — who fled here from Kosovo, is a maze of hastily-constructed family warrens, each separated from the next by blankets strung over ropes. Heat comes from unvented woodstoves. Goats and chickens share living quarters with young children and elders; infants swaddled in sweaters rock in rooms dimmed by smoke.

For almost a year after the first displaced persons arrived in June 1999, the Kursumlija shelter had no toilets or running water, said Slavica Parlic, who manages a program here for homeless Roma, funded by the Italian Consortium for Solidarity. Two toilets arrived last June, but there are still no proper containers for garbage, she says.

More than 650,000 people, mostly ethnic Serbs, have fled to Serbia since 1991, when a series of fratricidal wars ruptured the former Yugoslavia. Sheltering and feeding them is proving a crippling burden for Serbia, still struggling to recover from years of economic sanctions and months of NATO bombardment. The World Bank’s envoy to Belgrade, Christian Poortmaan, recently called the lack of energy, food and basic medicines for the refugees and displaced persons “an urgent crisis.”

But of all Serbia’s displaced people, among the worst off are the thousands of homeless Roma, members of a linguistically and culturally distinct minority who have for centuries been discriminated against, and sometimes persecuted, across Eastern Europe. Before the NATO bombing, there were at least 150,000 Roma in Kosovo, according to Miroslav Jovanovic, president of the Roma Democratic Forum. All but a few thousand were forced out, he says. “We came here to Belgrade and ended up sleeping in parks, living in cardboard boxes,” Jovanovic told a press conference called by Roma leaders last fall. “People spit on us.They called us dirty.”

Things are particularly bleak in Kursumlija. Even though the town was repeatedly hit during NATO’s 1999 bombing war, thousands of desperate Serbs, Roma, and even Albanians streamed in seeking a safe haven. Of the 9,000 people who found their way here after being burned out or pushed out of Kosovo, some 3,000 are Roma. Many are housed in private residences, but hundreds more are enduring a second winter in squalid, increasingly desperate conditions.

“The town’s resources are severely over-strained,” warns Ann Pesic, country director for the International Council of Volunteer Agencies, an umbrella group for NGOs in Yugoslavia.

On the banks of the Toplica River, a Roma family of 20 lives in two large tents under a bridge. One disabled man pivots in his wheelchair, his range of motion hemmed in by the riverbank on one side and a ditch on the other. The tents are not weatherized, so the quest for firewood is a constant preoccupation.

Firewood is a crucial commodity everywhere in town. Inside the town’s 250-seat movie theater, the proprietor shows off a colossal tin-drum stove that will heat the hall for an ICS-sponsored arts program and health clinic for Roma children. But with a wheelbarrow full of wood fetching $15 and monthly salaries rarely exceeding $40, “heating this place will be a major, major challenge,” said Martina Iannizzotto, country coordinator for ICS.

Before the NATO war, trains and buses from Belgrade passed through this area en route to points all over Kosovo province. Residents could also travel east to Bulgaria or west to vacation spots on the coast of Montenegro.

Now the train route ends in Kursumlija, where refugees account for almost half of the town’s population of 22,000. More than 70 percent of Kursumlija’s residents receive some kind of humanitarian aid, says ICS’s Parlic.

“Even before the war, the economy here was in ruins,” says Parlic, 35. “Now, Kursumlija is the poorest town in Serbia.” The crushing load of refugees is compounded by the area’s lack of jobs and its isolation from more prosperous cities in northern Serbia.

“Anyone with a chance has already left,” Parlic says. “What remains is an overwhelming load of poor people falling on an already collapsed society.”

The refugee issue poses a major challenge for Yugoslavia’s newly-elected president, Vojislav Kostunica. His administration is trying to push neighboring Croatia and Bosnia to simplify and accelerate repatriation of former residents who want to return to farms and homes they abandoned during the past decade’s wars.

This will not be easy. Both countries are also facing economic hardships, and returning refugees have faced discrimination. Last summer, an average of about 150 refugees returned to Croatia each week, according to the UN High Commissioner for Refugees — hardly an impressive number five years after the signing of the 1995 Dayton Peace Accords.

Repatriating the Roma of Kursumlija could prove an even more intractable problem. Clashes continue to accelerate in the border area between remnants of the ethnic Albanian Kosovo Liberation Army and Yugoslav forces.

Kosovo’s Roma are widely believed by Albanian Kosovars to have collaborated with the Serbs during the fighting there. Last November, four returning Roma were shot dead in a Kosovo village, according to NATO.

As a result, Lipa Berisa, 53, a father of three who says he lost his wife to an errant NATO bomb, is unlikely to return to Kosovo anytime soon. Last September, says Berisa, he visited his home in Obilic — the village he was forced out of in June 1999 — under the protection of peacekeeping troops. He says all 300 of the town’s Roma homes had been destroyed by arson fires, as had seven Serb-owned houses. Only the residences of three elderly Serb neighbors remained intact, he says.

“This was the first time I dared go back to see my village,” says Berisa. It may be a long time before he sees it again.