Image: Michael McDonald

When Patrick Barrett applied for a small business loan from the state of Hawaii’s Office of Hawaiian Affairs last September, he knew his chances for approval were pretty grim. For starters, Barrett has never run his own business — in fact, he hasn’t held a job in over 25 years. And there was another little sticking point: OHA’s loan fund is specifically reserved for native Hawaiians, and Barrett is white.

But when his application was sent back, Barrett didn’t go away; he went to court. He is suing the state of Hawaii in federal court, contending that the statutes that created OHA and other privileges for native Hawaiians violate his Constitutional right to equal protection under the law because he is not “a member of the preferred race.” If it succeeds, Barrett’s case will imperil OHA’s $380-million trust fund, which covers everything from college scholarships to home loans and cultural grants, the Department of Hawaiian Homelands’ 200,000-acre land trust, and the leases of 7,000 native Hawaiians currently living on that land.

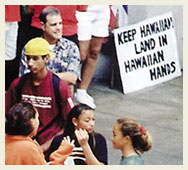

The lawsuit has sparked a furious response since its filing in October. The state attorney general’s office and high-powered legal teams representing OHA, homestead groups and Ilioulaokalani, a coalition of cultural practitioners, are mobilizing to fight it in court. Protesters have staged a rally at the state Capitol and at Maui’s Kahului Airport, where hundreds turned out in February, some carrying signs saying “Save Hawaii, Stop Barrett.”

Pretrial motions in the case are now being considered by a federal district court in Honolulu, where Barrett’s legal team is seeking an injunction to freeze all publicly funded programs for native Hawaiians. If the case loses there, John Goemans, Barrett’s Honolulu-based lawyer, vows to appeal it all the way to the US Supreme Court.

Even Barrett’s opponents believe there’s a strong possibility the Supreme Court will indeed end up taking on the issue. Last year, the court handed down a ruling in a case entitled Rice v. Cayetano which nullified a state law barring non-Hawaiians from voting for OHA trustees; Goemans plans to invoke that as a key precedent in the Barrett case.

The Rice case was a key victory for Goemans, who represented the plaintiff, and for his supporters in the nationwide anti-affirmative action movement. Goemans is being backed up on the Barrett suit by William Helfand, a Texas-based attorney who has made a career of attacking race-based programs around the country, from school admissions policies to busing programs. Helfand works closely with the Campaign for a Colorblind America, which recently merged with California affirmative-action buster Ward Connerly’s American Civil Rights Institute.

University of Southern California constitutional law expert Erwin Chemerinsky agrees that the Rice decision gives the Barrett case a good shot at making it to the Supreme Court, but the outcome there is far from certain. “Rice is about a specific election,” he points out. “That doesn’t mean that [the Supreme Court] is going to automatically extend that to everything else.”

Goemans, however, believes that Rice provides him with critical ammunition to attack the scores of state and federal programs that specifically benefit native Hawaiians. Those programs were created to help remedy the damage done to Hawaii’s native people by Western colonialist powers, from the introduction of TB, syphilis and gonorrhea by Captain Cook’s crew in 1778 to the imprisonment of Queen Lili’uokalani, Hawaii’s last reigning monarch, by a US-backed “provisional government” in 1895. Native Hawaiians, who constitute about 20 percent of the islands’ population, continue to suffer high rates of unemployment, incarceration and poverty.

Surprisingly, Barrett doesn’t want the native Hawaiian programs dismantled — he just wants his piece of the pie. Barrett is poor and physically disabled, Goemans says, and therefore needs the state’s help as much as anyone. But Robert Klein, a former state supreme court justice and one of the attorneys defending the the programs, says that’s not the point. “It’s not Mr. Barrett’s ancestors who were in such a deprived condition in 1921 that the US government said that if we don’t do something to help rehabilitate this race, there won’t be anyone left to rehabilitate,” says Klein, a native Hawaiian.

The case will likely hinge on whether the court views native Hawaiians as a racial group, or as an indigenous nation that has a special relationship with the US government based on past mistreatment. Unlike Native American tribes, native Hawaiians are not recognized by Congress as a distinct indigenous group (a bill to grant them such status is pending before Congress). If the court declares “Native Hawaiian” a racial classification, the state of Hawaii will have a much tougher time defending its affirmative-action programs.

Goemans, for his part, dismisses the notion that native Hawaiians should be awarded the same status as American Indians. “They’re not indigenous peoples, nor aboriginal peoples,” because they lack a common language or religion, he says. “They’re completely assimilated, wherever they happen to be. A big chunk of them are in L.A. and Las Vegas.”

Even if Goemans manages to sidestep the historical reasons behind the creation of native Hawaiian programs, his client is hardly an ideal plaintiff to carry his case. Barrett’s application included only his name, P.O. box, and a request for $10,000; his threadbare resume, Klein points out, doesn’t exactly make him a prime loan grantee.

But if the court does hear the case, it will rule on the principle involved, not Barrett’s business acumen. Klein admits that he’s in for an uphill battle, given the recent Supreme Court ruling. “We protect snails more than we do Hawaiians,” says Klein. “We should be on the endangered species list. We’d get more sympathy.”