Image: Andrew Lichtenstein

As delegates from 34 nations in the Americas and the Caribbean prepare to gather in Quebec City for the April 20-22 Summit of the Americas — a conclave designed to lay the groundwork for an eventual free trade zone from Hudson Bay to Patagonia — I find myself thinking about a meeting I attended last fall in Washington, D.C. I’d flown in from my home in West Texas at the expense of one of the nation’s largest philanthropic foundations to participate in a three-hour roundtable discussion on globalization.

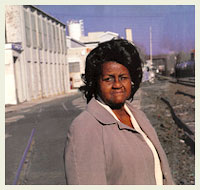

Seated around the table in the private dining room of a swank hotel near Dupont Circle were a dozen or so brand-name academics and journalists — State Department types shuttling to think tanks, think-tankers shuttling to the State Department. As near as I could tell, I’d been invited as the author of Mollie’s Job, an account of the effects of globalization on two women: Mollie James, a Paterson, New Jersey factory worker who loses her job when her plant relocates to Matamoros, Mexico, and the young Mexican woman, Balbina Duque, who inherits that job. (See the Mother Jones magazine article on James and Duque).

The point of the meeting, other than munching on salmon and caramelized onions and fresh field greens, was to assist the foundation in identifying areas in which it might “contribute meaningfully to public and political discussion of globalization.” To that end, the foundation’s resident pollster asked us to opine about his proposed “global public opinion survey.” Did we think it worthwhile for the foundation to sponsor a poll to gauge public attitudes toward globalization? If so, how should such a survey be structured? What themes, issues or specific questions should be addressed?

I nodded in smiling agreement at most of the sentiments expressed, even when the Washington Post business reporter said, apropos of nothing in particular, “I think everyone here has been to China more than once.” It was such a great non sequitur that six months later I continue to use it. “See them clouds?” the cowboy in line behind me in the express lane of my hometown grocery inquires of the cowboy behind him. “Think we’ll get some?” “I think everyone here has been to China more than once,” I soothsay. The Stetsons nod affirmatively. Really. Try it sometime.

Where was I? Yes, the global survey: how to elicit the views of affected citizens around the world. Focus groups, someone said. Interviews with “opinion leaders,” another volunteered. “What about peasants, campesinos?” asked a former foreign correspondent. “Why bother polling campesinos?” scoffed the perfectly pleasant and coiffed gentleman on afternoon leave from the Council on Foreign Relations.

The sentiment was seconded by a chipper Young Turk across the table, an up-and-coming pundit who enjoyed quoting from his own writing. (“As I say in my Times op-ed piece…”) The foundation, he said, would just spend a lot of time and money in jungles and rural areas trying to elicit the opinions of people who wouldn’t understand the questions and issues anyway. The Turk said this with a tone of such absolute authority, it surpassed arrogance.

My first impulse was to stomp out of there, but I refrained — there was, after all, an honorarium to collect. “You’re kidding, right?” I blurted instead. “Look, I’m not sure why I was invited here, but I took my invitation as a proxy for the women I wrote about. And I can tell you that to sit here and categorically declare that workers don’t understand the consequences of free trade, don’t understand the degradation of their environment, of their civil rights and civil liberties.” I trailed off, face flushed, lips pursed, not quick enough on my feet to finish with a flourish.

A few days later I asked Mollie James what she would have said. “You think I don’t get what happened to me, brother?” she replied. “You think I don’t know that by paying Balbina slave wages, they could take away my job?” Judging from the official pronouncement leading up to this weekend’s summit — preparations included the selling of event sponsorships to global corporations — organizers indeed assume that the Mollie Jameses and Balbina Duques don’t know, and wouldn’t understand.