Photo: <a href="http://www.debramcclinton.com" target="new">Debra McClinton</a>

Colorado state highway 135, along the Gunnison River, threads a landscape

that could be anywhere from Arizona to Idaho, Nevada to the foot of the Rockies. Valley after valley

floats a handful of cottonwood and aspen trees in a dry ocean of sagebrush, the pale gray green running

out the flats and over the hills. Lizards and rattlesnakes, hard sandy soil and the smell of the American

West — it’s the kind of wide-open emptiness in which you’d never want to find yourself on foot

with a long way to go. But I was driving, en route to a meadow in the Elk Mountains, the site of an unusual

global warming experiment. So the sagebrush yielded soon enough to the sweet high-country fragrance

of the evergreens, and then the snow-speckled peaks appeared, and with them that ineffable feeling

of being above and away from it all.

I suppose everybody favors a particular landscape, whether it’s the Northeastern

forest or the Louisiana bayou — a function of familiarity, temperament, memory. For me,

after 25 years of backpacking and climbing in the Sierra Nevada, it’s the meadows of the high ranges,

the patches of grass and flowers in the austere cobalt of an alpine sky. I do still want a “peak

experience” from time to time, but when I sit at my desk and think of the mountains, I think mostly

of the crimson columbine and the Indian paintbrush, of drying off from a frigid swim and sleeping

in the sunshine among the mariposa lilies. The mountain meadow, in my view, is rivaled only by the

tropical beach as a vision of our proper home in the natural world, an earth seemingly made for our

delight. Subalpine meadows in particular, meaning those below tree line, are also among the very

jewels of our national parks, from the Cascades to the Rockies, and if you’ve ever yearned to visit

Yosemite, you’ve yearned in large part for their solace. The snowcapped peak behind a lake or a creek,

the blossoms in the foreground — mountain meadows are the bread and butter of our great outdoor

image makers, be it Albert Bierstadt’s romanticism, the cool modernism of Ansel Adams, or the color-saturated

photography of Galen Rowell. They are also at the heart of what American conservationists

have fought to preserve for more than a century.

Highway 135 terminates at Crested Butte, a Victorian ski village doing

a respectable summer business around its official status as the Wildflower Capital of Colorado.

A cheerful, positive-attitude kind of place, Crested Butte teems with fresh-faced twentysomethings

carrying climbing ropes into fudge shops, and the drama of steep stone and sweeping green is so omnipresent,

so central to the town’s survival, that travel agents, art galleries, and even a widely publicized

wildflower festival all traffic in the sheer glory of the local color. (A popular book on the area

is called Wild About Wildflowers: Extreme Botanizing in Crested Butte.)

To see that color up close — and to face the lousy likelihood that

it will disappear, not just from here but from the mountains back home, and all in my lifetime — I

came to Crested Butte early last fall. I took County Road 317 out of town, up to the nearby ski area.

Bulldozers were scalping the earth for condos, and the chairlifts had that embarrassed off-season

look, their metal monstrousness and clearcut ski runs unredeemed by the clean white of winter snow.

Then 317 turned to dirt and a tributary of the Gunnison fell steep and deep to my right, a tight creek

booming through a precipitous canyon. A hand-carved wooden sign nailed to a post soon told me I was

entering “Gothic, Colorado,” and I found myself in what could easily have been the set for a Hollywood

Western. Gothic was a silver-mining town before it went bust in the 1880s, and its weather-beaten

shacks and old general store sat empty until 1928, when Gothic became the permanent home

of the Rocky Mountain Biological Laboratory (RMBL, or “Rumble,” as it is known to locals).

I parked by the creek in the bottom of the valley, Gothic Mountain broken

and grand in the western sky. Hiking a slope to the east, I rose above one of the world’s great mountain

scenes, trout leaping in the lazy creek and a breeze ruffling the spruce trees. Cresting a small

rise, I finally arrived at my destination: a curving, hundred-yard sweep of grasses and blossoms

marked at all four corners by 10-foot steel towers connected by heavy steel cables. More cables

hung crosswise, suspending the big array of infrared heat lamps strung up by U.C. Berkeley professor

John Harte in 1990. Harte has kept the lamps on for 14 years now, baking this living swath of meadow

to create real warming, in real time, in a real ecosystem. No fussing around with historical temperature

records, no computer modeling of hypotheses, and thus no vulnerability to the claim that it’s all

conjecture; Harte has simply warmed a piece of the world and watched it change. So festooned is the

meadow with data-collection boxes, and so riddled with multicolored wires plunging into its flesh — sinking

temperature and moisture monitors to three different depths — that the whole thing looks

less like a meadow than like a patient nailed to an operating table.

The verdict? Sagebrush is already crowding out everything that makes

a meadow a meadow in the first place — the colors and textures and birds and bees. And similar

experiments, not just in the Rockies and my own beloved Sierra, but also in the Alps and on the Himalayan

plateau, suggest that all such dreamscapes, by century’s end, will be as stark as the semiarid drive

up from Gunnison. And sure, this might not be an economic disaster for anybody but ranchers and the

denizens of mountain tourist towns, and it’s nothing like the damage a fast-warming world will

cause elsewhere, to the island nations and coastal cities sinking beneath the waves. Still, the

drying up of our high mountain retreats — and the fading away of other places equally lovely — is

the way that global warming will forever alter what Wallace Stegner called “the geography of hope.”

The national news cycle first highlighted

the plight of the mountain meadows in June 2002, when the Environmental Protection Agency released

its Climate Action Report. In it, the administration finally acknowledged that global warming

was both a reality and man-made, and that it would precipitate the slow disappearance of Florida’s

coral reefs, the barrier islands of the Southeast, and mountain meadows. The evidence on meadows

was based, in part, on the heated grassland at Gothic, the place Harte calls his “warming meadow.”

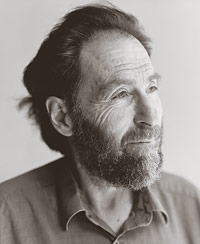

A serious and driven man, with a shaggy brown 1970s beard and a jogger’s taut build, Harte, 64, started

his career as a Yale physics professor. He got interested in ecology after a Vietnam War teach-in,

and soon took a job at Berkeley, joining the Energy and Resources Group, an advanced environmental

studies program. He made his first pilgrimage to RMBL in 1977 — to study acid rain in local

lakes — and he’s been back every summer since, occupying the same little cabin since 1980.

The most immediate result of Harte’s experiment is also the most obvious — stand

there by the heat lamps and you don’t need a tour guide to point out the encroaching sagebrush, a verdant

lawn on its way to becoming desert. But Harte has also found that the advancing sagebrush causes

a cascade of reinforcing changes — an ecological feedback loop. It turns out, for example,

that wildflowers and sagebrush participate very differently in the atmospheric carbon cycle,

the process by which plants take carbon dioxide — the main component of the greenhouse effect — out

of the air and make leaves and flowers and stems from it, which then die and fall to the ground. Bugs

and worms decompose that litter into organic carbon in the soil, which then gets eaten by microorganisms

that release it back into the atmosphere in the form of carbon dioxide. Wildflowers are highly active

photosynthesizers, which is to say that they take a lot of carbon from the atmosphere and make a large

amount of leaves, flowers, and stems every year. They also shed all that above-ground material

every autumn, dumping it back into the soil. Wild-flower litter is relatively easy for microorganisms

to digest, so it readily breaks down into carbon dioxide and re-enters the atmosphere.

As the world warms, and we enter the first part of the meadow-to-sagebrush

transition, the effect will be much like the clearcutting of tropical rainforests. All the carbon

bound up in those plants will be released into the air — it happens through the burning of clearcut

debris in the Amazon and through decomposition in meadows — but with an ever-diminishing

photosynthesis to pull the carbon dioxide back into more plants on the other side of the cycle. Harte

tested the effect of this by comparing the amount of organic carbon in the soil of his warmed plots

with that in his control plots. For the last five years, he’s found a steady diminishment of carbon

under the lamps — more and more of it vacating the meadow for good and therefore remaining

airborne as carbon dioxide, further warming the atmosphere and further encouraging the spread

of sagebrush. Sagebrush does its own photosynthesis, and Harte expects that its proliferation

will bring a small recovery in soil organic carbon, but not nearly enough to offset the loss of the

meadows. Sagebrush also has a much lower albedo than wildflowers — that is, it reflects less

sunlight back into space, causing even more warming and even better conditions for more sagebrush.

Much like the melting of the polar ice caps, the loss of mountain meadows is both an indicator of global

warming and a contributing cause. As the meadows vanish, a beneficial feedback loop — in

which their high albedo helps to cool the world — is replaced by a harmful one.

The 2002 EPA report that referenced Harte’s work was one of the administration’s

now-infamous “Friday surprises,” and it included the official government stance on the greenhouse

effect: “Adapting to a changing climate is inevitable. The question is whether we adapt poorly

or well.” When news of the EPA’s findings broke, President Bush dismissed them as “the work of the

bureaucracy.” The heart of the Rocky Mountains and the Sierra Nevada, the very pearls of our public

lands, will soon fade away. But if taking action might be costly to the energy industry, forget about

it. Oh, and have a nice weekend.

It would be a lot easier to have a nice weekend

if all this were merely forecasting, but even outside the pale of Harte’s lamps, Gothic’s meadow

life shows the distinct effect of the global warming that’s well under way. Billy Barr, a wiry 53-year-old

from Newark, New Jersey, has observed much of this with his own eyes. Barr got his first RMBL job studying

water quality in 1972, and he loved the place so much he never left; as the lab’s business manager,

Barr is Gothic’s only year-round resident, living alone in a cabin throughout the snowy winter.

With long scraggly hair — blond going gray — and an equally scraggly beard, Barr has

a jumpy physicality, and the serene intensity that comes only from genuine solitude. He’s not a

trained scientist, but in the process of passing a life up here, Barr has recorded detailed observations

of nearly 20 animal species. Sharing those findings with RMBL scientists, he’s helped identify

trends that are in some ways more disturbing than the encroaching sagebrush.

Yellow-bellied marmots, who fatten themselves all summer and then

hibernate, burrow up in the spring to peek out like Punxsutawney Phil. They make a decision, then,

about whether to stay awake or to hibernate for another month. Billy Barr skis to and from his office

in the winter, and he’s often on hand when those first marmot noses break the surface and the rodents

make their call about whether or not to stick around. Because Barr is a good observer, we now know

that marmots make that call based less on the amount of snow cover than on the air temperature, and

that they are emerging 38 days earlier than they did when Barr started paying attention a quarter

century ago. Which is not so terrible in and of itself, except that they’re emerging with as much

as six feet of snow covering everything they eat, putting them at a very real risk of starvation.

David Inouye, a University of Maryland biologist who has spent more

than 25 summers counting flowers in Gothic, is documenting similar problems with the meadow’s

birds. Most of them overwinter elsewhere, like the broad-tailed and rufous hummingbirds that

pass the cold months in central Mexico, migrating back in summer to drink flow-er nectar and make

their chicks on high. The hummingbird migration depends on the synchronization between the end

of the relatively warm winter in Mexico and the beginning of the temperate summer in the Elk Mountains;

when it gets too hot in Mexico, thank goodness, the snow’s already melting in the Elks. Trouble is,

that’s not quite true anymore. Lower-elevation growing seasons — such as those in Mexico — are

changing at a faster rate than higher-elevation growing seasons. Which leaves birds, programmed

by evolution, without a clue. American robins, responding to greater heat in lower altitudes,

arrive now at Gothic fully two weeks earlier than they did in 1981, and they are doubtless a little

disturbed by all the snow still hiding every worm around.

The life cycles of meadow denizens synch up slowly with local (and distant)

seasons over millennia, and past climate changes have taken place gradually enough for these cycles

to adapt. The EPA predicts that by 2100 the average global temperature will have risen five degrees

Fahrenheit, the same magnitude of warming as seen in the last 1,500 years, a genuinely dramatic

acceleration already disrupting the meadow’s intricately orchestrated systems. Higher temperatures,

for example, mean an earlier spring snowmelt, which means an earlier first flowering. Purple larkspur,

one of the first flowers to pop up after the ground goes bare, now puts out vulnerable buds in early

June, despite the still very real possibility of a snap frost. If that frost comes — all it

takes is one cold night — those buds will die. This means no seed for new larkspur plants, of

course, but also no nectar for the long-tongued queen bumblebees who need to produce their worker

bees and begin their hives, and no blossom clusters for the male broad-tailed hummingbirds who

should be just arriving from Mexico. If the birds and the bees show up to no larkspur, they’ll stray

away for food, they’ll have less luck making offspring, and they won’t be around for the scarlet

gilias that bloom in midsummer and need help with pollination. No pollination means no future gilias,

and thus no future midsummer nectar for the other birds and bees. The ripple spreads, the butterfly

causing the hurricane that leaves the bird out in the cold. “That’s going to be common,” Inouye tells

me. “Environmental events and biological events that once made sense together are losing their

synchrony.”

And so it goes, the hungry robin wondering

why the warmth down in the valley didn’t mean springtime up high; the marmot wishing he’d

slept a little later; the sagebrush turning out to be the nuclear cockroach of climate

change, spreading its arid silence. The world is already changing, in other words, by a thousand

small cuts. Rising sea levels in the Atlantic have swallowed the coastal mangrove forests of Bermuda

and fully one-third of the marsh at Blackwater National Wildlife Refuge on the Chesapeake Bay.

The warming Pacific has wiped out 20 amphibian species in the Costa Rican rainforests and 90 percent

of California’s sooty shearwater seabirds, and melted so much Canadian sea ice that polar bears

are starving and freak bouts of freezing rain have cut the number of British Columbia’s Peary caribou

from 24,000 in 1961 to as few as 1,100 in 1997. The Inuit of Banks Island now regularly see things never

before witnessed by their people, like robins and barn swallows, and thunder and lightning. Each

and every one of these details is a thread in a fabric just like the Rocky Mountains. And each and every

one heralds a similar unraveling.

There’s a temptation to imagine that all these changes are just that — changes.

Global warming skeptics often cite the fact that the earth perpetually cycles through natural

heating and cooling trends, and we are indeed in the midst of one of the former. But this heating spurt

is taking place much too fast, and there’s a limit to how quickly a mead- ow can head north or higher

up a mountain in order to stay cool. “Can meadows pack their suitcases and make it?” Harte asked.

“That’s a big question.” He wore a pressed blue shirt that day, and a belt buckle enameled with stars

and planets — a leftover, perhaps, from his physics days. “I can’t prove it,” he said, deep

brown eyes intent, “but in my bones, I have no doubt that Gothic is going to look like Gunnison one

day. Remember those opening scenes in The Sound of Music — Maria cavorting in the Austrian

meadows? Well, imagine if those scenes were filmed outside Reno.”

Peace, renewal, hope — the mountain mead- dow signifies something

of value, even to those who’ve never had the privilege of visiting one. I’ve seen an Elk Mountain

meadow used to advertise flat-panel computer monitors, Mount Rainier wildflowers in SUV commercials,

and posters from the Crested Butte Wildflower Festival being sold in suburban Boston. When people

actually visit these places, they do it for the same reasons I go to the High Sierra — for the

air and the rock climbing, the quiet pleasures of bird-watching and plant identification. High

on that list is also the simple happiness of wild places, that indescribable lifting of the spirit.

In the high, clean green, and in the impossibly lovely sprinkle of glacier lilies, there’s a ready

access to the wonderful feeling that Freud considered the wellspring of all religion. After initially

dismissing God as pure illusion, Freud took to heart a letter from a respected friend insisting

that he’d missed a crucial point — that “the true source of religious sentiments…consists

in a peculiar feeling…a sensation of ‘eternity,’ a feeling as of something limitless, unbounded —

as it were, oceanic.” Having never experienced this emotion himself, Freud could only explain

it as a holdover from an unresolved childhood, a boundaryless connection to mother and father.

But it’s more than that, of course, and better. It’s the very real sense of being embedded in the world,

inescapably implicated in natural cycles so much larger and older than ourselves. I have to believe

that if more of us had a chance to know that feeling, we’d know also that we can’t keep tipping the balance

of this earth without losing more than we can ever hope to gain.