Photographs: Henry Leutwyler

AT 2:57 P.M. ON THURSDAY, JULY 1, 1993, a nondescript man stepped off an elevator on the 34th floor of 101 California St., a sleek, granite high-rise in downtown San Francisco, and entered the plush law offices of Pettit & Martin. Dressed in a dark business suit and carrying a black attaché case, he might have passed for an attorney returning from a late lunch.

He set his case down and from beneath his jacket pulled out three semiautomatic pistols, which he came prepared to reload with hundreds of rounds of ammunition. He calmly walked 60 feet toward a glass-walled conference room where lawyers were deposing a witness in a labor dispute, and opened fire.

The plate glass shattered. Two people—the plaintiff in the case and her lawyer—were killed instantly; two others were wounded, one shot in the arm as she dove for cover behind a chair. Heading around the perimeter of the office, the gunman blasted through the glass wall of a Pettit partner’s office, killing him. As the shooting spree continued, people scurried behind doors and desks and ran for exits. Someone pulled a fire alarm, which caused some people to believe that all the commotion was just a drill. As SWAT teams arrived, and the address system repeatedly warned people to lock their doors and stay inside, the gunman moved down the stairwell to other floors occupied by Pettit.

Only later would all the pieces be put together: the newly married 28-year-old surfer-turned-lawyer shot to death shielding his wife, the San Francisco Fire Department chaplain administering last rites to the dying. About 15 minutes after he started shooting, as he was descending to the 29th floor, the gunman encountered cops coming up the stairs. He pointed a pistol at his chin and pulled the trigger.

Gian Luigi Ferri was a loner, a would-be real estate tycoon who’d had limited dealings with Pettit & Martin on a botched deal years earlier and irrationally blamed the firm for his subsequent failures. He’d been harboring his rage for more than a decade, railing in a letter found on his body against a “List of Criminals, Rapists, Racketeers, Lobbyists,” including Pettit lawyers. In all, Ferri killed eight people and wounded six in what a police official called “the worst mass homicide tragedy in San Francisco’s history.”

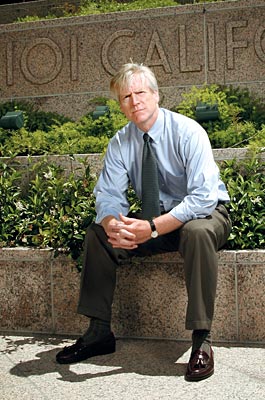

One of those who emerged a changed man from that Thursday 12 years ago was John Heisse, a Pettit lawyer who’s now a partner in the San Francisco offices of Thelen, Reid & Priest, a large national firm. Tall, white-haired, and patrician, Heisse seems the picture of well-groomed composure. But as he describes those long-ago moments, he turns his face away, his eyes still haunted. “I stepped over the body of a kid—a law student who had worked for me,” he says, his voice cracking mid-sentence. “I had several friends who died.” After the shootings, Heisse found a new cause in antigun activism, cofounding the Legal Community Against Violence. When Pettit dissolved in the mid-’90s, Heisse and a dozen other lawyers who’d survived the shooting were picked up by Thelen, which over time came to see the tragedy as part of its own institutional history.

In 2004 that history prompted Thelen to team up with New York Mayor Michael Bloomberg to wage a landmark lawsuit against more than three dozen gun manufacturers and distributors. The companies—including Beretta, Smith & Wesson, Glock, and Browning—constitute virtually the entire firearms industry. New York City’s case is built on the theory that gun companies know their products end up being trafficked to criminals and could take easy steps to stop it, but fail to do so. Thelen has been working pro bono on the case for a year, donating seven lawyers to the effort full time, and even putting its vice chairman, Michael Elkin, in charge of the case.

When a jury starts hearing New York v. Beretta this fall in Brooklyn Federal Court, it will be the first time such a lawsuit brought by a municipality has made it to trial. A victory would be such a significant feat that GOP members of Congress, in a move some observers think is aimed at this lawsuit, are pushing for sweeping liability protection for the industry. Nonetheless, gun-control advocates see in the New York case a real possibility to force manufacturers to change the way they market and distribute their products. Even a partial victory could embolden other jurisdictions to bring cases and erode the industry’s clout, just as early successes cracked Big Tobacco.

Attorney John Heisse survived the shooting at this building that claimed the lives of several colleagues. Twelve years later, his firm is taking on the gun industry.

IT’S A PARADOX that has frustrated law enforcement agents for decades: New York City has some of the strictest gun laws in the country—you can’t buy a firearm if you don’t have a license, are under 21, a felon, or have a mental disorder—yet thousands of such off-limits customers wind up with weapons, and the overwhelming majority of guns used to commit crimes were originally sold in perfect compliance with the law.

The explanation, experts say, is that traffickers import guns to New York, where the tight laws and, at least in certain areas, high demand drive up the price of illegal firearms. Traffickers know they can reap huge profits buying guns in the South, where prices are low and look-the-other-way dealers proliferate. New York v. Beretta alleges that the industry is well aware of the middlemen—gun shows, kitchen-table dealers, straw purchasers, and buyers who purchase in obviously excessive quantities—through which traffickers get the Attorney John Heisse survived the shooting at this building that claimed the lives of several colleagues. Previous spread: Guns used in New York City crimes. guns bound for the city’s black market.

However traffickers procure them, many guns ultimately used in New York crime travel along I-95, a highway that New York cops have dubbed the “Iron Pipeline.” Running from Florida up the East Coast, “it exemplifies the big problem New York faces,” says Joe Vince, a 28-year veteran of the Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco, Firearms and Explosives (ATF) and an expert witness for the plaintiffs. “In Ohio, for instance, the majority of guns come from in-state. But in New York, people are loading up on guns hundreds of miles from the city. How can the cops police that? It’s ATF who has jurisdiction over interstate trafficking, but ATF only has 2,000 agents for 50 states. So very few traffickers are ever caught or prosecuted.”

By the late ’90s, gun-control advocates and municipal officials across the country started examining how corrupt dealers who feed such black markets get their goods. They found that the vast majority of gun dealers are law abiding, meaning that the payoff from zeroing in on the dirty ones could be disproportionately great. According to one widely cited study published by the Clinton administration in 2000, just 1.2 percent of dealers accounted for more than 57 percent of the guns used in crimes nationwide. If gun companies stopped their products from getting into the hands of such dealers, far fewer guns would flow into the local black markets—leading, it’s hoped, to a commensurate drop in violent crime.

Beginning with New Orleans in 1998, a number of municipalities struck out in a bold new direction, suing gun manufacturers and distributors to recoup the medical and law enforcement costs of gun violence. Many built their cases around “trace data” compiled by the ATF. When a gun is used in a crime and recovered, the ATF retraces the path of the weapon from manufacturer up through any transactions conducted by licensed dealers. This information is not publicly available, but manufacturers have had access to it, which could enable them, adversaries say, to gauge which dealers are selling guns eventually used in crimes. They could be monitoring problem dealers and even cutting them off, but so far, few of them appear to have done so. That failure, some of the lawsuits have charged, amounts to callous, even willful negligence—the result of a reluctance to cut into profits made off of corrupt dealers. By this calculus, the actions of the industry lead to a grimmer conclusion: that gun companies actually help to create a black market. An analysis of ATF data performed by the National Economic Research Association found that 11 percent of guns sold in 1996 had been used in a violent crime by 2000. “It’s become obvious that the crime gun market has been a huge segment of the gun industry’s sales,” says Brian Siebel, a senior attorney at the Brady Center to Prevent Gun Violence. “It’s been a share of the market they haven’t been willing to surrender.”

Industry spokespeople insist that manufacturers aren’t trained in law enforcement and are “no more responsible for criminal misuse of their product than Budweiser is responsible for drunk driving,” in the words of Lawrence Keane, general counsel of the National Shooting Sports Foundation (NSSF), a well-funded industry group. What’s more, gun companies have “done more than any other industry” to prevent bad sales and promote safety, says John Renzulli, a lawyer representing Glock and Browning, citing a program to educate dealers about straw purchases.

Rudolph Giuliani launched New York’s lawsuit in 2000. He’d just dropped out of the New York Senate race and, no longer beholden to the NRA or national Republicans for financial contributions, he was more concerned with burnishing his legacy of battling crime. To that end, the suit was perfect. The legal term of art for the large-scale injury and death that resulted from industry’s lack of self-policing was decidedly understated: the gun companies were creating a “public nuisance.” The city’s top lawyer (known as the corporation counsel) explained in a press conference that “our major claim would be that the gun industry is guilty of negligent marketing and distribution.” He vowed to recoup “tens of millions of dollars and maybe more.”

Despite the big promises, little at the time indicated that New York had much chance of winning. A number of municipalities had brought similar cases, but none had succeeded in getting to trial. Individual victims of gun violence had won scattered cash settlements here and there, but they hadn’t achieved anything approaching industry reform, and most had used different theories of liability. The year before, the NAACP had filed a public-nuisance suit on behalf of its members—in effect, potential victims of gun violence—trying to force a change in the industry’s marketing practices, but that effort was not yet far along.

Indeed, the gun companies seemed confident that legal precedent was on their side. “Time after time, the courts have held that a manufacturer of a safe, nondefective product is not responsible for its criminal use,” said Bob Delfay, then-president of the NSSF, when the New York suit was filed. “We’re hoping Giuliani will regain his sanity by morning.”

Delfay was cocky, but then again, the suit was far from a slam dunk. New York City had to make a different kind of argument from plaintiffs in traditional liability suits, in which manufacturers are held responsible for defective products, rather than ones that work all too well. Judges have shown resistance to cases that smack of regulating an industry through the courts (which is why a state appeals panel would later toss a similar suit brought by New York Attorney General Eliot Spitzer). Gun companies had latched on to an argument that, without documented proof to the contrary, seemed plausible—namely, that their guns were sold and resold so many times en route to the streets that they couldn’t know for sure which dealers were corrupt.

To counter this argument, the NAACP had subpoenaed the ATF trace data from 1995 to 1999. The industry found an ally in the ATF, which refused to comply with the subpoena. But the courts were another matter: In 2002 Judge Jack Weinstein, who heard the NAACP case in Brooklyn Federal Court, directed the ATF to turn over the information.

Saying that the NAACP couldn’t show that its members had suffered a different kind of harm from industry practices than other New Yorkers, Weinstein subsequently dismissed the group’s case, meaning that the ATF trace data would, for the time being, remain privileged. Nonetheless, Weinstein’s decision appeared to set a precedent for future plaintiffs that such records could be pried loose. More important, he was sympathetic to the public-nuisance argument, writing in his opinion of the industry’s “failure to take elementary steps” that “would have saved the lives of many people.” Indeed, he found that while the industry had improved its practices in recent years, “these steps are late, too few and even now insufficiently embraced by most individual defendants to eliminate or even appreciably reduce the public nuisance they individually and collectively have created.”

Among those who took particular interest in Weinstein’s decision were the city lawyers arguing New York’s lawsuit. Under court rules that steer cases to judges who’ve heard related litigation, the judge hearing New York City’s case was none other than Jack Weinstein.

A FEW YEARS OF PRETRIAL maneuvering passed, and suddenly New York’s corporation counsel, Michael Cardozo, had a big problem on his hands. The gun industry’s motion to dismiss the city’s case had been rejected by Weinstein. While this virtually ensured that the case would soon be the first of its kind to go to trial, it also seemed to prompt the white-shoe law firm that had been helping the city, Weil, Gotshal & Manges, to pull out of the case.

According to the New York Times, Weil Gotshal was spurred to step aside after a Smith & Wesson attorney called a client—one who also happened to be a client of Weil Gotshal. That client then reportedly expressed concern to Weil Gotshal that the city’s suit against the gun companies could undermine the client’s interests. A Weil Gotshal lawyer told the Times that its client might have a point: that even the appearance of a conflict could leave it open to the charge that it softened its advocacy for the city.

Cardozo had to act fast. His boss, Mayor Michael Bloomberg, was if anything a bigger proponent of suing the gun industry than Giuliani had been. He regularly asks for briefings on the case and frequently plugs it on his radio show. Cardozo called his old colleague Michael Elkin, who’s now vice chairman at Thelen, and asked for help. Elkin, who trained to be a social worker before entering law, is today better known for repping clients like Bob Dylan, Billy Joel, and James Taylor against Internet music pirates than for public-interest work.

The request gave Elkin pause—Weil Gotshal’s exit read like a cautionary tale of the gun industry’s clout. Reluctant to risk a similar fallout from corporate clients, and wary of the damage that might be done to the firm’s lobbying practice, some Thelen partners weighed in against taking on the suit. “When you take on such an explosive social issue, there’s a chance that you’re going to offend a good number of people who can take their legal business elsewhere,” Elkin says. “We expected client resistance.”

But Elkin was also mindful of the firm’s history. He asked Heisse to vet the case, and Heisse decided it was winnable. Indeed, to listen to gun-control advocates, a perfect storm of circumstances surrounds this case. On top of what was implied by Weinstein’s NAACP decision, Bloomberg administration lawyers had refined the lawsuit, giving up on monetary damages and instead seeking only industry policing of marketing and distribution practices—an aim that puts a victory more within reach. Perhaps most important, for the first time a jury was likely to see the trace data and related evidence accumulated in other lawsuits; at the very least, the industry’s inner workings would get a public airing. “This was a cause the firm had historical connections to,” Elkin says. “We were on the right side of the issue, and we felt this case could have far-reaching impact.”

Thelen decided to take on the case and named Elkin to head the team. As he predicted, there were business repercussions. One of Thelen’s clients, a gun company called Kimber that is not a defendant in the New York City suit, subsequently fired the firm. But to gun-control advocates, Thelen’s entry into the case—so far the firm has donated $1.5 million of billable time—has only heightened hopes. “You’ve got one of the top law firms in the country putting some of their best litigators into this effort,” says Jonathan Lowy, another BradyCenter senior attorney. “They’re treating this case like they do their most highly paid clients.”

IN A CONFERENCE room high above midtown Manhattan, a half-dozen young lawyers on the Thelen team are sitting around a large table. Scores of boxes filled with legal papers are piled floor-to-ceiling. “It’s as if they all went to the same deposition prep school,” says associate Gabriel Nugent, alluding to how gun company executives seem well trained at evading questions. Nugent remarks on the problem of getting them to submit to cross-examination on the stand. “There’s no way that any of these guys are coming to New York,” he says.

Elkin, wiry and energetic, challenges his associates to turn a negative into an advantage. “The issue of compelling testimony is a double-edged sword for the defendants,” he says. “If they can’t make it to trial, there’s something you can color for the jury. Say, ‘Look, if this person cared so much about making sure his side of the story was adequately presented, they would have made the trip here. It’s not too difficult in this day and age to get on Jet Blue and get your butt before a federal court.’ There’s a certain arrogance to not showing your face before a jury.” As his listeners nod, Elkin tries to elevate the discussion from questions of process. “We’re asking an industry that has not regulated itself in order to reduce harm and danger to society to take some responsibility,” he says. “You are all doing your level best to fulfill a very important social mission. And I want to thank you.” Moments later, his charges file out, visibly energized.

In different conference rooms, gun company lawyers are working on their own aggressive strategy. The industry has hired 19 law firms to fight the city. It’s also enlisted its allies in Washington to protect it from the rising tide of litigation, including the New York suit.

Congress is currently considering a far-reaching bill—sponsored by Rep. Cliff Stearns (R-Fla.) and Senator Larry Craig (R-Idaho), who’s a board member of the NRA—that would grant the entire firearms industry immunity from a broad swath of liability lawsuits. Similar legislation passed the House in 2003 but was rejected by the Senate last year. That, of course, was a different Senate, and at press time the bill’s passage seems likely, though what impact it could have on New York v. Beretta remains up in the air. Both sides say they expect to go to trial, suggesting that Weinstein could declare the law unconstitutional or find that it doesn’t apply retroactively. “Judge Weinstein is a very creative guy,” says NSSF counsel Keane. “He will find a way to make sure this case goes to trial.”

Meanwhile, pretrial skirmishing, especially around the critical trace data evidence, has been heated. New York tried to get its hands on even more data than the NAACP had wrested from the ATF before its case died. But industry—backed by government allies—struck back repeatedly. In 2004, Rep. Todd Tiahrt (R-Kan.) even inserted a provision into an appropriations bill barring the use of subpoena power over ATF trace data. The agency dragged its feet on coughing up the information until June of 2004, when Weinstein ruled that the data had to be released to plaintiffs’ lawyers.

The prospect of exposing such records at trial is already a victory, say gun-control advocates. “Not only will it identify the worst gun dealers in America, but it will also show beyond any doubt that the gun industry is profiting from sales to criminals carried out through those very same dealers,” says the Brady Center’s Brian Siebel.</b>

Still, the city’s legal hurdles are considerable. As there’s no precedent linking industry sales practices to a public nuisance, “the first challenge is to show that the defendants owe the plaintiffs a legal duty, not just a moral or ethical one,” says Ralph Stein, a professor at Pace University School of Law who’s followed the case. Ironically, another disadvantage that the city faces is the perception that New York City is now very safe, compounded by the fact that some in the jury—the jurisdiction includes suburban (and fairly conservative) areas like Nassau and Suffolk counties—may be well insulated from violent crime. “We may not be able to say that the average commuter is feeling the nuisance,” concedes Nugent, who won’t get into too many strategic details about the trial. Another potential weak spot in the city’s suit is that it doesn’t center on the sort of tragic plaintiff juries respond to. “It has to bring home to the jury that the city’s action, if successful, would protect all New Yorkers, starting with these 12 people,” says Stein.

Thelen partner Thomas Lane insists that the city will bring drama to the courtoom. “We’re certainly going to use specific stories about gun violence victims,” he says, though there’s a question as to what Weinstein will let in. Regardless, under the public-nuisance claim, the city doesn’t have to prove that the industry intended any harm, or colluded, or had any particular motive like increasing its profits. It only has to prove that the defendants’ conduct contributes to or maintains a public nuisance. And there, Lane stresses, “a dramatic statistical pattern” will make the city’s case.

Further help may come from testimony by at least one insider. Robert Ricker, a onetime NRA and trade association official, testified in the NAACP lawsuit that the industry is deliberately ignoring the problems posed by unsupervised dealers, saying, “if the industry took voluntary action, it would be admitting responsibility.” Plaintiffs may also introduce an article penned by a firearms dealer, Robert Lockett, for the industry trade magazine Shooting Sport Retailer. “Let’s just get down and dirty. We manufacture, distribute, and retail items of deadly force,” Lockett wrote, adding that arguments “regarding lack of accountability [have been] pretty flimsy. Today, they are tenuous at best.”

Gun companies haven’t disputed that their products are used to commit crimes. But, says Glock attorney Renzulli, “just because there are guns available to bad people does not mean there is liability.” Dealers get duped—something manufacturers and distributors can’t prevent—and if guns used in crimes get traced back to them, it merely reflects that they do a large volume of business. Indeed, Nugent says he expects the industry to argue that, as “one big family,” it doesn’t tolerate dirty dealers.

The NSSF has already starting spinning a potential court loss, attacking Weinstein’s credibility. The 84-year-old judge, famous in legal circles for wrestling long-stalemated litigation over Agent Orange to settlement, is known for forgoing a robe, sitting among lawyers instead of on the bench, and taking bold, even activist, positions. Since the suit was filed, the NSSF has attempted to turn him into a bête noire of gun owners, depicting him as a zealot on a “decade-long crusade to destroy the firearms industry.”

“If the city wins, it will only be because of Weinstein,” says Keane, the NSSF general counsel. “His decisions all but ensure that the victory would later get overturned by an unbiased appellate court.” That’s overstating the case, but Pace law professor Stein agrees that the city’s biggest hurdle may be with the appellate court and not the jury. “Judge Weinstein, while a wonderful judicial curmudgeon, has been reversed on appeal quite often,” he notes.

Twelve years after the tragedy that still haunts his firm, and as he prepares to launch what may be the most significant case in the history of gun litigation, Michael Elkin is confident of both short- and long-term victory. “These manufacturers have escaped responsibility for far too long,” he says. “Their day of reckoning is coming.”