Earlier this month, after some high-stakes brinkmanship on both sides, the European Union opened formal membership talks with Turkey. The mere fact of the negotiations, which mark the latest stage in a long and arduous process that began in 1953, when Turkey first applied to join the E.U., is hugely significant. Just to be considered for membership, Turkey has had to undertake a top-to-bottom reform of its political arrangements, its laws, and its economy, and reassess some of its most basic cultural assumptions. For all its progress, though, the country has a long way to go before its institutions and norms are fully aligned with Europe’s—a bedrock precondition for membership—and success is hardly guaranteed even then. Under the most optimistic scenario, Turkey could be admitted to the E.U. as a full and equal partner in about ten years.

Turks, on the whole, want their country in the E.U. They hanker after the economic benefits that flow from having free access to the world’s largest single market, and they view admission as the fulfillment of an aspiration, first formulated in the 1920s by Mustafa Kemal Ataturk, the country’s founder, that Turkey should take its rightful place among the world’s first-rank powers as a prosperous, secular, fully modern nation.

Plenty of Europeans, of course, have their doubts. In a recent poll only 35 percent of E.U. citizens said they favored Turkish membership; political leaders, too, are split: Tony Blair, for instance, is a strong advocate—on the grounds that by accepting Turkey Europe would decisively debunk the pernicious myth that Islamic and Western worlds are destined unavoidably to clash; others, like the new German chancellor Angela Merkel, argue that the country is too different culturally from Europe for any merger to work.

But nor are Turks uniformly pro-E.U. In fact, large numbers are deeply ambivalent about the liberalizing process required by Brussels, seeing it as a threat to the integrity of the Turkish state and Turkish identity. In order to pass E.U. muster, for instance, Turkey will somehow have to come to terms with its large, impoverished, and periodically insurgent Kurdish population; it must resolve, in concert with Greece and the union, the question of Cyprus; it will have to complete the work, already far advanced, of removing the Turkish military from political life, which it has dominated—sometimes quite openly, other times covertly—throughout the 80-year history of the republic; and it will have to loosen restrictions on the public expression of Islamic piety. Crucially, the Turkish state will have to permit public discussion of these and other taboo issues. (Many topics remain off limits in Turkey today: consider that the country’s most famous novelist, Orhan Pamuk, was recently charged with “humiliating Turkish identity,” having observed, in an interview, that Turkey was overdue for some public soul-searching about its treatment of the Armenians (in 1915) and the Kurds. He stands trial in December and faces up to three years in jail if convicted.)

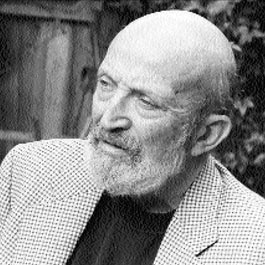

Andrew Mango, who was born in Istanbul, is optimistic that Turkey will eventually take its place among the world’s modern liberal democracies. But he knows Turkey too well—knows its plentiful contradictions and ambiguities—to blithely assume that its path of reform will be easy. Mango, who worked for 40 years at the BBC, is the author of Ataturk, a monumental biography of the Turkish nation’s founder and guiding spirit, and, more recently, The Turks Today, the definitive English-language work on modern Turkey. He recently spoke by phone with Mother Jones from London, where he now lives.

Mother Jones: Turkey has made great progress down the path of liberal reform in recent years. And yet, the country’s best known novelist, Orhan Pamuk, was recently indicted for making some fairly mild comments about Turkey’s need to confront its past. What to make of the contradiction?

Andrew Mango: One should remember that this is a decision by a single public prosecutor in Turkey, and in Turkey, as in many European countries, public prosecutors can initiate proceedings on their own initiative. Second, the Turkish judiciary has a very strong nationalist tradition, which is gradually changing, but only gradually. And since there was a nationalist outcry against Pamuk’s remarks, I’m not surprised that one public prosecutor in an Istanbul borough should have decided to act. I don’t expect the proceedings to lead to a conviction. But in any case one mustn’t generalize and say that’s the way Turkey behaves; it’s the way one nationalist public prosecutor behaves.

MJ: Even so, the mixed reaction to Pamuk’s comments—some Turks backed him, others were incensed—suggests at least an ambivalence in Turkish society about hitching the Turkey to the West.

AM: Turkey’s relationship with the West is a love-hate one. There are people in Turkey who want to open to the outside world and others who are frightened of the outside world. They don’t feel secure; they think that foreigners are trying to harm or even destroy Turkey. But that’s not true of the majority of Turks, who want to exercise their skills in a global market.

MJ: What are Turkish nationalists afraid of?

AM: That the country’s sovereignty will be watered down; that law and order might be compromised—and these fears are not totally groundless. You know, there was a time when Istanbul was one of the safest cities in the world, because people were afraid of the police. People are no longer as afraid of the police as they used to be. Mugging used to be almost unknown; now everybody is afraid of mugging. In that sense, the downside of liberalization is already being felt in Turkey. And of course some people are afraid of Kurdish ethno-terrorism, which worries Turks very much more than the religious sort.

MJ: Throughout Turkish history the military has been one of the key players—until recently the key player—in the country’s political life. How do the generals feel about Turkey’s bid to join the E.U.?

AM: They have contradictory feelings about it. On the one hand they feel that they’re guardians of Ataturk’s legacy, which meant Westernizing, coming closer to Europe. So it’s what the Turkish army, as a modernizing force, has always pushed for. On the other hand they’re afraid that liberal attitudes toward dissent would damage the cohesion of Turkish society. The generals are always talking about “fraternal unity,” and of the army as the expression of fraternal unity. You have to realize that the Turks come from very many ethnic origins, and so the generals are afraid that Kurdish nationalism might lead to a nationalism of refugees from the Caucasus, from Bosnians, Albanians, and that Turkish society would break up into a mosaic, a Babel of competing ethnic groups. I think that fear is exaggerated, except in the case of Kurdish nationalism.

MJ: In recent years the military has gradually been eased out of political life. Is there ambivalence about that among the generals?

AM: There is. But as far as legislation is concerned, the requirements of the European Union have been met. The military budget is now subject to much more parliamentary scrutiny than before. The National Security Council, through which the military used to exercise influence over the government is now a purely consultative body.

On the other hand, Turkish society can’t change overnight. And Turkish society sees the military as the guarantor of law and order. The army is trusted, held in high regard—though not, obviously, by dissident liberals. When things go wrong, people expect the military to intervene, as they’ve intervened over and over again in Turkish history. That’s not going to change overnight.

MJ: Why should we in the West care whether or not Turkey successfully modernizes or gets into the E.U.?

AM: Accepting Turkey as a member of the European club means that the club is open to outsiders, to Muslims, to poorer people, to developing countries, to countries with a slightly different cultural tradition but basically the same values. I think it’s dangerous for us to close the door; it doesn’t do us any good and it doesn’t do the rest of the world any good. Also, it reduces the danger of a “clash of civilizations.”

There are of course economic advantages to having Turkey in. It’s a developing country with a large, reasonably well-trained labor force at a time when the European birth rate is dropping at a catastrophic rate and Europe is graying. It offers opportunities for greater trade and investment to the benefit of both Turkey and Europe.

MJ: Nevertheless, there’s opposition in Europe to Turkish membership.

AM: That’s true. These are the inevitable fears of energetic, poorer, Muslim outsiders who will come in and work hard and take jobs. There’s also a fear that under E.U. rules Turkey might get a disproportionate amount of cohesion funds and agricultural subsidies—although it’s quite clear that Europe is changing its rules, and that there will not be very much in the way of net transfers of resources from Europe to Turkey.

MJ: And anyway, Turkey’s economy is developing reasonably well, isn’t it?

AM: Yes. Turkey has had a customs union with Europe since 1996, and there’s free trade in everything other than farm products and services. And Turkey has shown that it can compete. It’s good at making cheap goods—household appliances, food, detergents, cheap clothes. And they make a lot of white goods, cheap TVs, washing machines, electric appliances, steel, and, recently, auto parts. And Turks are gradually moving into IT.

MJ: But historically Turkey hasn’t had much success in attracting foreign investment. Is that changing?

AM: Slowly. There’s a tradition of arbitrary decisions by government ministers and senior civil servants, which would ruin businesses from one day to the next, and which has tended to deter foreign investment. That’s changing, and convergence with E.U. practices is a good thing in that it improves governance.

MJ: It’s been suggested that Turkey should be accorded something less than full membership, some kind of privileged status. Could Turkey live with that?

AM: Well, this is not the time to discuss it. Let’s see whether, within ten years, Turkey’s full membership is agreed or not. And if it isn’t, you see what is possible short of that. Of course, Turkey already has privileged status: it’s the only non-E.U. country that’s got a customs union with the E.U.

MJ: There are concerns in the West about the status of women in Turkey. Are they justified?

AM: It’s important to differentiate. Istanbul and the western and southern seaboards are very Europeanized. But then you have the Kurdish areas, in the southeast. That’s Turkey’s Middle East, where you have a different society, which itself is changing but much more slowly, where women are maltreated, are expected to have huge families, and are often basically beasts of burden. That is changing—with education, with the movement of people from the southeast to the west and the cities. As with so much in Turkey, you can’t expect change to happen overnight.

MJ: What about human rights more broadly? Turkey has an poor record there. Has there been progress on that front?

AM: They’ve improved a great deal, but progress on human rights depends on the degree of law and order. We’ve seen in Europe after the recent terrorist attacks a certain retrogression in human rights. It depends on how threatened the Turks feel. For example, Turkey became much more tolerant towards Kurdish nationalists when the killing of Turkish soldiers stopped in southeastern Turkey and body bags stopped arriving. Now, since June there’s been a revival of Kurdish attacks on Turkish troops—something like 150 people have been killed by terrorists supplied from and operating out of bases in northern Iraq. So Turks are feeling much less tolerant of Kurdish nationalism.

MJ: Kurds have it pretty hard in Turkey. What should the Turkish state be doing to improve their condition?

AM: Most Turkish Kurds want a quiet life and improved economic conditions. But the Kurdish regions of Turkey are mountainous; they’re ill-favored climatically; they’re poor; and there’s a limit to what the government can do there without wasting a lot of resources. Developing the south east may mean decamping a large part of its population. But the thing that will improve the lot of the Kurds more than anything else will be the stabilization of Iraq in the first place, because then the Turkish southeast stops being a dead end. It can become a bridge, with trade flowing in both directions.

MJ: The Turkish government today is dominated by an Islamist party, and the prime minister, Recep Tayyip Erdogan, is was jailed a few years ago for reciting a poem extolling militant Islam. Despite his background, he has moved Turkey in a liberal, reformist direction faster and more comprehensively than any of his predecessors. How to make sense of that?

AM: I think he has genuinely changed, as he has said himself. He comes, like most of his supporters, from a less privileged part of society. Although Erdogan went to faith school he then went on to university and got a degree in economics, and a lot of his people have got degrees in modern disciplines. They come from outside the establishment, but they found their way in by peaceful means. They’re not an anti-system party, as Islamic fundamentalists are; they are secularists. In Turkey religion not only affects society but is affected by it, which is why Turkish Islam differs from Arab Islam. It’s a more modern, more rational, more self-confident society. Granted, Erdogan has conservative instincts on, say, family values—respect, honor, and all the rest of it—but I think you’ll find that his and his followers’ children will see things differently.

MJ: Modern Turkey, throughout its history, has been stringently secular. Observers have nonetheless noted a revival in public piety in recent years. Is this an important trend?

AM: It’s a bit like the piety of Victorian England. As things change people find in religious observance a certain framework of safety, of continuity. This is quite a common phenomenon. In a strange way it’s part of a democratization of society. Although religious observance seems more common these days, it’s not that people who did not go to mosques have started to go to mosques. I don’t know anyone in Turkey who’s become a born-again Muslim. It’s a question of individual choice, and it does not stop the organic secularization of Turkish society, which carries on regardless.

MJ: How are Turkey’s relations with its immediate neighbors?

AM: They’ re improving. They were pretty bad for a long time—with Syria they were abominable, and with Iran they were pretty bad. In both cases Turkey sees potential for trade, especially with Iran, where it gets a lot of natural gas. In good times Iran and Turkey find mutually profitable objects of exchange, but with Syria things have been very bad; Syria doesn’t have much money and never will.

MJ: Turkey’s relationship with the United States came under strain in 2003, when Turkey refused to grant transit rights to the American forces invading Iraq. How are relations two years later?

AM: That was a very difficult decision even for the most intelligent and pragmatic Turks to work out what was in the national interest. Would it be better to let the Americans in and therefore have a presence and a say in Northern Iraq? Or to deny them transit rights and avoid mobilizing Arab opinion against Turkey? Even the generals couldn’t make up their minds. When people in Turkey ask me, Do you think we were right? I use a variation on Chou en Lai’s remark about the French Revolution: “It’s too early to tell.”

Of course, it affected Turkish-American relations at the time. But I think basically there’s a realization that there’s a common interest in stability, in rational government, will draw the two countries together. Turkey, as an ex-imperial power, is all in favor of empires guaranteeing law and order on its borders. Turkey’s and America’s basic interests with regard to Iraq are identical. They both want a stable and rational Iraq that would use its considerable oil wealth in order to improve its own lot. But there doesn’t seem to be very much prospect of that at the moment.

MJ So, to wrap up, how optimistic are you that Turkey will continue on its path of reform? And do you think it will eventually be welcomed into the E.U.?

AM: I’m optimistic about Turkey’s prospects for reaching the E.U.’s standards of development, governance, and democracy, whether inside or outside the E.U. Provided you have a prosperous, rational society in Turkey that can interact with Europe and the West, I don’t really care what kind of institutional arrangement you have. The point to make about Turkey and Europe is that it’s a very long, drawn-out process. What’s important is that the process not be stopped, that Turkey and Europe evolve in the right direction, on a path of convergence. Convergence is the name of the game.