Maggie Williams brings back memories—and baggage. The new campaign manager for Senator Hillary Clinton’s presidential campaign, who replaced Patti Solis Doyle earlier this week, was chief of staff for First Lady Clinton. In that role, she became a bit player in two major Clinton War battles of the 1990s: Whitewater and the campaign-fundraising scandal, which included allegations that China had tried to illegally funnel donations to the Democratic Party. In each case, Williams was the target of conservative suspicions about the Clinton gang—some overheated—but she escaped any real trouble. Her involvement in the White House fundraising caper, though, did raise questions about her credibility.

Whitewater was a mess of a scandal. It began with allegations about a real-estate partnership the Clintons incorporated in Arkansas in 1979 with a dodgy banker named James McDougal, and spread to include the suicide of deputy White House counsel Vince Foster, and, later, Bill Clinton’s extramarital affair with Monica Lewinsky. After Foster’s body was found on July 20, 1993 in Fort Marcy Park above the Potomac River, right-wing journalists and agitators cooked up and promoted wild theories connecting his death—or murder!—with the Whitewater scandal. The allegation was rubbish. But one part of the scandal centered on the charge that high-ranking Clinton officials, after hearing of Foster’s death, quickly cleared his office of supposedly incriminating documents related to Whitewater. Williams, Clinton antagonists claimed, was part of this conspiracy.

During the Republican-led Whitewater hearings held in the Senate in 1995, GOP senators tried to nail Williams. Pointing to phone records that showed dozens of phone calls among Williams, Hillary Clinton, White House counsel Bernard Nussbaum, and Susan Thomases, a Hillary pal, Republican senators suggested this group had conspired to remove documents from Foster’s office before investigators probing his death could examine them. Yet the investigation produced no solid evidence. A Secret Service agent did testify that he saw Williams leaving with files, but she denied doing so and submitted to two lie detector tests, which registered no deception on her part. (She maintained that she had transferred files out of the office only after investigators were done with them.)

The whole Whitewater/Foster to-do was a blur of allegations. Foster’s death was repeatedly ruled a suicide. And in the end, neither the Clintons nor their aides (including Williams) were charged with any wrongdoing.

During the campaign-finance investigation, plenty of sleazy fundraising practices (of both Democrats and Republicans) were probed by House and Senate committees. Williams, for her part, became ensnared in an episode involving Johnny Chung, a Taiwan-born businessman and prominent contributor to the Democratic National Committee. A frequent White House visitor, Chung often hung out in the First Lady’s office staring—literally—at pictures of Hillary Clinton. Williams’ assistant, Evan Ryan, testified that that the First Lady’s staff found Chung’s visits “disturbing.” But Williams told Senate investigators that because Chung was a “contributor,” she instructed her office to treat him with respect, like “any other irritable jerk who would show up.”

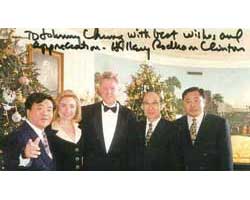

On December 19, 1994 the DNC received a $40,000 donation from Chung, and the next day he was allowed to bring a delegation of Chinese businessmen to the White House residence for a holiday reception, where Chung and the gang had their pictures taken with Bill and Hillary Clinton. Several months later, Chung asked Hillary Clinton’s office for help on several fronts. He wanted a photo with Hillary, a tour of the premises, lunch in the White House mess, and an invitation to bring another delegation of Chinese business associates to 1600 Pennsylvania Avenue to attend the President’s weekly radio address. Ryan, Williams’ assistant, testified that she had told her boss about these requests and informed Williams that Chung intended to make a contribution to the Democratic Party. According to Ryan, Williams instructed her to help Chung and mentioned that perhaps the Democratic Party could use a donation from Chung to pay the White House money it was owed by the party. (The DNC, like other organizations, had to pay for expenses related to events it held at the White House.)

Chung’s request was granted, and on March 9, 1995, he and his business pals were escorted by Ryan to the White House for lunch, given a private tour, and were taken to the Map Room for a photo op with the First Lady. Afterwards, Chung handed Williams a donation to the DNC, this time for $50,000. That weekend, he and his business associates attended the President’s radio address.

A key issue was whether Williams and the First Lady’s office had traded favors at the White House for campaign cash. In testimony before the Senate governmental affairs committee, Williams denied she had asked for the donation and said there had been no quid pro quo. She insisted that Chung had essentially shoved an unsolicited check into her hand and that she immediately dropped it in her outbox for forwarding to the DNC—without even looking at the amount. She said that it was not unusual for Hillary Clinton’s office to receive unsolicited contributions for the Democratic Party in the mail and that her aides routinely sent them on to the DNC. Chung told a different story, claiming Williams and Ryan had requested the donation.

Overall, Chung contributed $366,000 to the DNC between 1994 and 1996 (and eventually there were questions about whether this was his own money or whether he was fronting for other sources, including the Chinese government). It was pretty obvious at the time that he was looking to impress his business associates with the access those gifts won him. And that was a central part of the Clinton fundraising scandal: the selling (or renting) of access to whomever would donate big bucks to the DNC. Those who did so could brag to friends, clients, and business connections that they were well-wired into the Clinton White House—and perhaps that helped them grease their own business deals. This sort of quasi-scam was not a Democratic or Clintonian sin. But the Clinton White House did perfect the art. (It is illegal to solicit or receive political contributions in government offices, but it was not clear if taking a check and placing it in an outbox—as Williams said she did with Chung’s donation—was a violation of the law.) In 1997, the DNC returned Chung’s contributions.

In testimony before the Senate government affairs committee—then chaired by Republican Fred Thompson—Williams downplayed the Chung episode. But on a few key points Ryan, her assistant, contradicted her. Years later, it’s not unreasonable to look at the record and conclude that Williams was part of a shifty system in which the Clinton White House would hand out favors (maybe just small ones) for anyone brandishing a check—and that she might have stepped over the line in following this standard operating procedure.

After leaving the White House in 1997, Williams, who’d previously worked for the Children’s Defense Fund, spent several years in Paris as a communications consultant. She later returned to the U.S. and became president of Fenton Communications, a public relations firm that represents many progressive outfits and causes. Back in Hillary’s employ since January, she’s a reminder that the Clinton administration—beyond the trumped-up Whitewater matter and the much-exploited Lewinsky affair—had its share of legitimate ethics troubles. In 1997, Chung famously said, “I see the White House is like a subway: You have to put in coins to open the gates.” Williams, according to Chung, was one of the collectors. Now she’s Hillary Clinton’s conductor.