Photo: Alex Tehrani

Harlem on election night was, predictably, a little nuts. At 11 p.m., when the networks declared that Barack Obama would be the next president, church bells rang and champagne flowed. Old women hollered. Young men wept. There was, quite literally, dancing in the streets. Among the people parading down 125th Street that night, Obama’s victory was seen as a deliverance, not just for the nation but for the neighborhood as well.

And Harlem has long needed delivering. Poverty has always been a fact of life in the United States, but the concentrated urban poverty that Harlem—along with sections of every American city—has experienced in the past half-century is a relatively new phenomenon. In the 1950s and 1960s, middle-class blacks, less constrained by restrictions on where they could live, began to move out of neighborhoods like Harlem in great numbers. At the same time, the postwar decline of the country’s manufacturing economy deprived the urban African American families who remained of the jobs that had sustained them. As a result, the number of poor people living in neighborhoods with at least a 40 percent poverty rate almost tripled during the 1970s in the five largest American cities. These areas became a brand-new kind of urban ghetto, almost all poor and all black.

The hope spilling out along 125th Street on the night of November 4 was for change of all kinds, from a more productive economy to a more benign foreign policy. But it was also a hope that President-elect Obama would be able, finally, to find a lasting solution to the kind of entrenched urban poverty that has engulfed Harlem and neighborhoods like it for decades.

During the Democratic primaries, Obama didn’t talk about poverty as much as John Edwards did. And in the general election, it was John McCain, not Obama, who took a weeklong “poverty tour” of blighted cities like New Orleans and Youngstown, Ohio. But Obama’s unique background—food stamps as a child, community organizing as a young man—seems to have given him an unusually sophisticated understanding of poverty’s causes and potential solutions. His poverty plan includes some basic Democratic solutions, like raising the minimum wage and increasing the Earned Income Tax Credit. But Obama has also proposed more targeted policies: guaranteed sick days to protect low-wage workers, for whom a bad cold can often lead directly to a pink slip; transportation subsidies to help inner-city workers get to better-paying jobs in the suburbs; child care programs to make it easier for single parents to hold down a job.

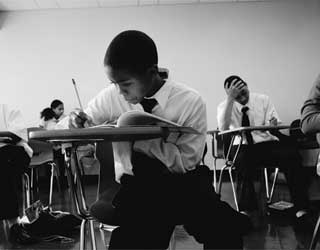

Beyond those more short-term measures, Obama promises an ambitious suite of programs intended to attack the deeper roots of inner-city poverty. The dismal employment situation in neighborhoods like Harlem doesn’t only have to do with the lack of good jobs. It also has to do with the fact that many poor people lack the skills necessary to get and keep those jobs, everything from basic math and reading ability to more subtle noncognitive skills, like patience and perseverance. Some of those deficits can be filled in through job training programs like Job Corps—but many of them cannot. In recent years, economists, social scientists, and neurologists have shown that the skills gap between rich kids and poor kids opens up very early, and the later you wait to address those deficits, the harder it becomes to turn things around.

The good news from this research, though, is that certain interventions do work, provided they start early and continue throughout childhood. One of the most rigorously evaluated is the Nurse-Family Partnership, a program, now operating in 350 counties across the nation, that sends registered nurses to conduct regular home visits with low-income women who are having their first child. The nurses act as mentors and counselors, encouraging the mothers to quit smoking, go back to school, and find constructive ways to deal with the stresses of new parenthood. The results are encouraging, even many years down the road—at age 15, kids whose mothers went through the program are 59 percent less likely to have an arrest record than teens in a control group. Currently, the program serves nearly 16,000 mothers; Obama has pledged to expand it to all low-income first-time mothers.

Even more ambitious is Obama’s plan to replicate the Harlem Children’s Zone, a program that I profile in my book, Whatever It Takes. The Zone is the brainchild of Geoffrey Canada, an African American man in his mid-50s who grew up in extreme poverty in the South Bronx. Canada escaped the inner city for Bowdoin and Harvard and then returned to New York to try to create better options for kids like the ones he grew up with. In the mid-’90s, he was running a decent-size nonprofit for teenagers in Harlem, and everyone told him how successful he was. But he could see only the kids he wasn’t helping. Poor children in Harlem faced so many disadvantages, he realized, that it didn’t make sense to address just one or two and ignore the rest. A great after-school program wouldn’t do much good if the school itself were lousy. And even the best school would have a hard time succeeding without help from the parents.

Canada’s solution was to take on all those problems simultaneously. The Harlem Children’s Zone takes a holistic approach, following children from cradle to college, mimicking the cocoon of stimulation and support that surrounds middle-class children. The Zone now enrolls more than 8,000 children a year in its various programs, which cover a 97-block section of central Harlem. “We’re not interested in saving 100 kids,” Canada told me once. “Even 300 kids. Even 1,000 kids to me is not going to do it. We want to be able to talk about how you save kids by the tens of thousands, because that’s how we’re losing them. We’re losing kids by the tens of thousands.”

Canada believes that many poor parents aren’t doing enough to prepare their kids for school—not because they don’t care, but because they simply don’t know the importance of early childhood stimulation. So the Zone starts with Baby College, nine weeks of parenting classes that focus on discipline and brain development. It continues with language-intensive prekindergarten, which feeds into a rigorous K-12 charter school with an extended day and an extended year. That academic “conveyor belt,” as Canada calls it, is supplemented by social programs: family counseling, a free health clinic, after-school tutoring, and a drop-in arts center for teenagers.

Canada’s early childhood programs are in many ways a response to research showing that the vocabularies of poor children usually lag significantly behind those of middle-class children. At the Harlem Gems prekindergarten, I watched as the four-year-olds were bombarded with books, stories, and flash cards—including some in French. The parents were enlisted, too; one morning, I went with a few families on a field trip to a local supermarket organized by the Harlem Children’s Zone. The point wasn’t to learn about nutrition, but rather about language—how to fill an everyday shopping trip with the kind of nonstop chatter that has become second nature to most upper-middle-class parents, full of questions about numbers and colors and letters and names. That chatter, social scientists have shown, has a huge effect on vocabulary and reading ability. And as we walked through the aisles, those conversations were going on everywhere: Is the carrot bumpy or smooth? What color is that apple? How many should we buy?

So far, Canada’s vision has yielded impressive results. Last year, the first conveyor-belt students reached the third grade and took their first statewide standardized tests. In reading, they scored above the New York City average, and in math they scored well above the state average.

Obama’s proposal is to replicate the Harlem Children’s Zone in 20 cities across the country. In his speech announcing the plan, he proposed that each new zone operate as a 50-50 partnership between the federal government and local philanthropists, businesses, and governments, and he estimated that the federal share of the cost would come to “a few billion dollars a year.” It’s an undertaking that would mark a seismic change in the way that we approach poverty.

Over the last few months, as I’ve talked to a variety of audiences about Canada’s program, I’ve heard one question over and over: Can it really be reproduced? It’s true that it took a leader with Canada’s unique qualities and personal history to create the first Harlem Children’s Zone, to inspire donors enough to expand it from a modest community organization into a nonprofit powerhouse with a $68 million annual budget. But replicating the Zone, especially with federal backing, will require a different and more attainable set of skills. In fact, as leaders around the country create their own versions of the Zone, they’ll likely improve on the model Canada has created—as well as, inevitably, make a few missteps.

The bigger question is whether Obama, once in office, will conclude that the government can’t now afford this kind of bold initiative. It may be that the plan will be put on hold for a year or two, until the worst of the downturn passes. But Obama, drawing on the research of his Hyde Park neighbor, the economist James Heckman, has made the point that programs like the Harlem Children’s Zone are not giveaways; they’re investments that will pay for themselves in reduced spending on welfare, job training, and the criminal justice system. As Obama put it, “We will find the money to do this because we can’t afford not to.”

Obama concluded his speech with a story. “The idea for the Harlem Children’s Zone began with a list,” he said. “It was a waiting list that Geoffrey Canada kept of all the children who couldn’t get into his program back when it was just a few blocks wide. It was 500 people long. And one day he looked at that list and thought, Why shouldn’t those 500 kids get the same chance in life as the 500 who were already in the program? Why not expand it to include those 500? Why not 5,000? Why not?

“And that, of course,” he continued, “is the final question about poverty in America. It’s the hopeful one that Bobby Kennedy was also famous for asking. Why not? It leaves the cynics without an answer, and it calls on the rest of us to get to work.”