In the Oval Office, surrounded by military officers and with Vice President Biden at his side, President Obama this morning signed several executive orders effectively reversing some of the most controversial Bush administration policies propagated during its “war on terrorism.” (Even that well-worn phrase was absent from the executive orders and, in a welcome change, has yet to be uttered by the new president…though White House Press Secretary Robert Gibbs today denied to Mother Jones‘ Washington Bureau Chief David Corn that the omission reflects an official change in rhetoric.)

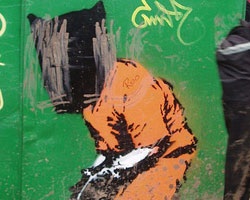

Obama signed three executive orders, (1) mandating that Guantanamo be closed within one year; (2) ordering that all interrogations be conducted in accordance with the Army Field Manual, even those conducted by the CIA, which had previously enjoyed greater latitude to pursue “harsh interrogation tactics” during the Bush years; and (3) establishing a special inter-agency task force to “provide me with information in terms of how we are able to deal with the disposition of some of the detainees that may be currently at Guantanamo that we cannot transfer to other countries,” Obama said at the signing ceremony. The new president also signed a memorandum asking that the Supreme Court delay proceedings related to detainee Ali Saleh Kahlah al-Marri, a legal US resident, until the administration has time to review his case.

Before entering the Oval Office for the signing ceremony, Obama and Biden met in the Roosevelt Room with several retired military leaders, who had advised the administration on how to deal with the contentious issues covered in today’s executive orders. Former Army Major General Paul Eaton and retired Navy admirals John Hutson and Lee Gunn spoke in a conference call this afternoon about their encounter with the new president and shared their thoughts on the impact of today’s event. They were joined by Elisa Massimino, executive director of Human Rights First, which organized the call.

As Gunn, a Clinton-era inspector general of the Department of the Navy, told reporters, “In the war against the kind of enemy we’re fighting now, it is arguably far more important that we be able to rely on allies, that we be able to trust our friends, and that they be able to trust us, and in the process that we share what’s vital to know and that we cooperate in the kind of preparations that are necessary in order to deal with this foe.” Speaking for his colleagues, he went on to say that many of the reasons for our strained alliances abroad “have been dealt with effectively today by the president almost immediately as he began his term.”

Not everyone is completely satisfied with today’s orders. The Center for Constitutional Rights, for example, which has organized a team of over 500 lawyers to represent Guantanamo detainees, issued a statement saying that closing Guantanamo a year from now “takes too much time… given the pressing issues at stake.” It also expressed concern that the order against harsh interrogation could be reversed in special circumstances. “We caution that the order may leave an escape hatch if the CIA should want more tactics, i.e. torture, available in its arsenal.”

The retired military officers on today’s call, however, tried to downplay concern, emphasizing the break with disastrous Bush-era policies. With regard to any wiggle that might be left in how the CIA interrogates detainees, Hutson declared that the door to the world’s secret network of black sites had been “slammed tight” by today’s executive order.

One of things missing entirely from Obama’s executive orders was any indication that past abuses (accusations of torture, for example) would be investigated and, where sufficient evidence of abuse is found, prosecuted in criminal courts. There had been calls for such a process during the presidential transition, but for now at least, the Obama administration is focusing on the future, said Gunn. “One of the things that we saw today was the nature of moving forward on the administration’s part. It’s clear that there will be substantial conversation in and out of the administration about what happens looking back and how we evaluate what we’ve done over the last several years. But at the moment—and it strikes me as being completely appropriate—the focus is on moving forward.” But even Gunn went on to admit that, with regard to the past, “not everything has been dealt with.”