Photo used under a Creative Commons license by flickr user <a href="http://www.flickr.com/photos/marcogomes/">Marco Gomes</a>

VIVIAN BLAKE’S WAR

In the late 1970s, a young Jamaican man named Vivian Blake, a scholarship kid from the Tivoli Gardens ghetto of Kingston, arrived in New York as part of a traveling cricket exhibition, stuck around, and began selling marijuana. One of the last great political proxy fights of the Cold War was then unfolding in Jamaica: Both the left-wing party, friendly to Castro, and its right-wing opponents built violent electioneering posses to persuade friendly voters and attack unfriendly ones—800 Jamaicans died. Blake was affiliated with the right-wing Shower Posse. He helped funnel pot and, later, cocaine to the United States and sent guns back home to help the posses intimidate voters. After the election, the new government tried to drive the posses off the island, and many arrived in New York and Miami, fully formed, violent organizations, deprived of their political purpose and looking for something to do.

In 1985, it was still possible to describe crack as confined to three cities—New York, Los Angeles, and Miami. But police elsewhere soon noticed two new phenomena: crack, and the Jamaican gangs who would soon control up to 40 percent of the East Coast market. Blake’s posse had built markets in Roanoke and Houston, Renkers Posse ran Philly and DC, and Kansas City and Des Moines were Waterhouse. The early traffic was thus partly a creature of Cold War politics: Blake and his contemporaries built the model for a national drug trade—the overweight, nondescript women couriers, the rented Volvos. After the cops clamped down, they discovered that the Crips and the Bloods had aped the Jamaican model, and taken over.

THE CHAMBERS BROS’ WAR

In 1986, it dawned upon the police chief of Marianna, Arkansas—a tiny, mostly black, cotton-cropping Delta town—that four brothers who’d relocated to Detroit three years earlier were recruiting away all of the town’s teenagers. Willie Lee, Billy Joe, Larry, and Otis Chambers ran half of Detroit’s crack trade, supplying 500 crack dens and operating 200 more; one scholar called their operation an “alternative to Little League.” Prosecutors found one Marianna teen working 24-hour days, passing parcels to addicts through a hole in the wall, caring sleepily for her baby when things got slow. The country kids were enmeshed in new rivalries, in shootings and murders. Then, in 1988, the empire abruptly dissolved: The Chambers brothers were convicted, and as their unemployed foot soldiers trickled home, Marianna’s police recorded new violence, and the appearance of crack. Back in DC, the episode made clear that even the country’s obscure corners were vulnerable.

JOE TOFT’S WAR

On September 29, 1994, a former DEA agent named Joseph Toft, well known in Colombia for his starring role in Pablo Escobar’s death the previous year, sat down with some TV reporters in Bogotá. Toft had just retired, and felt newly free to speak his mind. Escobar’s takedown, he said, was a sham; the whole operation—its politics, its execution—was designed to benefit the Cali cartel, whose leaders had enlisted the government to murder their top rival. The country, Toft said, was a “narcodemocracy.” American taxpayers had spent billions to transfer wealth from one thug to another.

Colombians from Gabriel García Márquez on down were outraged, but president Ernesto Samper, whom Toft had accused of corruption, was strangely, almost poetically plaintive. “Our tragedy,” he said, “is that we live in Technicolor, and the United States judges us in black and white.” Washington’s response was similarly measured: Toft no longer worked for the government, officials explained, but they declined to address the substantive point. Over time, the reason became clear: Samper, it is now alleged, had taken $6 million in campaign contributions from the Cali cartel, while Los Pepes, the patriotic hit squad formed to hunt Escobar, was chiefly composed of Cali soldiers, who got back to business once the unit disbanded. One, a notorious enforcer called Don Berna, would become one of the world’s most powerful cocaine kingpins.

Toft retired to Reno, disillusioned. His former bosses had always talked a two-prong strategy: policing to stem drug imports, and hard domestic work—rehab, economic initiatives—to cut demand. “It’s not a matter of the government putting out a few booklets, sending a few CDs to the schools,” Toft told me. “I’ve been very disappointed in the fact that we’ve never had a true effort where the US as a whole says, ‘We’re going to reduce demand.'”

JESUS AMEZCUA’S WAR

To the Mexican smugglers hired to run drugs across their northern border, the cocaine trade had long seemed cruelly weighted against them. The crossing was by far the riskiest step, and the one that added the most value to the product, yet the Colombians paid meagerly. The Mexicans couldn’t grow their own coca, so they felt in perpetual hock to the Andean kingpins. But in the early ’90s, a low-level Mexican trafficker named Jesus Amezcua stumbled upon a solution. During his trips to Southern California he’d discovered a growing market for methamphetamine. Here, Amezcua realized, was something he could produce himself.

By 1992, he’d built an international supply network, buying the chemical precursors from countries including India, Switzerland, and Czechoslovakia. It was an opportune moment: In the United States, the pharmaceutical industry was fighting efforts to restrict these chemicals, used to make cold remedies. Amezcua was able to feed the new demand, synthesizing meth in vast Mexican mountain laboratories, peasants openly hauling sacks of the stuff along dirt roads. DEA agents chasing the supply found themselves at factories in China and India, pondering a new reality. The game was no longer about cocaine. The organizations were breeding something more lasting: entrepreneurs.

JOHN CARNEVALE’S WAR

In the late 1990s, John Carnevale, longtime budget director for the Office of National Drug Control Policy, was asked to devise a metric to assess anti-drug tactics. Drug policy had long been consumed by moral bickering, with conservatives arguing for law and order and liberals for legalization, but up to that point, nobody really knew what worked.

Carnevale focused his algorithm on three measurable outcomes: Washington wanted to jack up drug prices, stifle imports, and reduce drug-related crime and health costs. Crunching the numbers, he determined that spending on domestic law enforcement was cost-effective, while policing efforts in Mexico and Colombia provided little bang for the buck. Some demand-side programs worked well, particularly ones that diverted hardcore addicts from jail into treatment. Others, notably ad campaigns intended to change the habits of young, casual users, did not.

The tragedy of Carnevale’s initiative was its timing. Barry McCaffrey, the Clinton drug czar who’d commissioned the study, opted to expend his political energy in a grandstanding attempt to fight medical marijuana in California. Then George W. Bush took over drug policy and, Carnevale told me, “shifted back to an ’80s-style budget,” heavy on overseas interdiction and anti-drug advertising—the least effective programs. Carnevale’s evidence-based approach never stood a chance.

TEO’S WAR

Drug trafficking has evolved in fits and starts, punctuated by periodic brainstorms from entrepreneurs like Blake, Amezcua, and recently Teodoro García Simental—a midlevel Tijuana drug enforcer. Teo’s brainstorm was that his particular skill set—intimidating people on behalf of the traffickers, kidnapping them, and, when the need arose, eliminating them—had grown so refined that he no longer needed the drug trade. He abandoned his cartel following an April shoot-out with his old bosses that left 14 dead on a Tijuana expressway. He aimed to turn pure violence into profit.

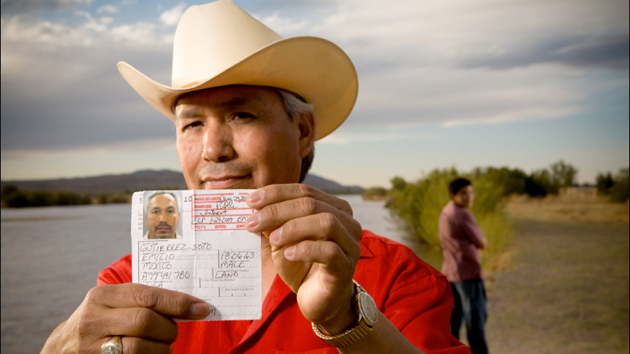

The plan was simple: Kidnap the rich, for ransom. By May 2008, so many of the city’s doctors had been snatched—some speculated that Teo’s organization was running through the phone directory—that they called a general strike. In January, police finally captured one of Teo’s lieutenants, whom they accused of dissolving 300 bodies in vats of lye.

Teo’s insight was that corruption had so crippled the state that he could operate freely. His mere presence—tauntingly beyond the reach of police, who can’t even find a decent mug shot for wanted posters—suggests the scale of the task the Obama administration faces. Not long ago, it was still possible to talk about fixing our mutual problems with smart drug policy—targeted policing, better border security, and strategies to cut demand. But so corroded is Mexico’s government now that its problems—in Tijuana at least—may require a wholesale resurrection of the state. These are the conditions that gave rise to Teo. The traffic has created, once again, a thousand children, ambitious, talented, and hungry for opportunity.