Photo courtesy of Flickr user <a href="http://www.flickr.com/photos/dvids/" target="blank">DVIDSHUB</a>.

It was March 2002, and Del and Barbara Spier were flat broke. The Texas couple, grandparents of five and owners of a small, Houston-based private investigations firm, were more than $260,000 in debt. They carried balances as high as $18,600 on more than a dozen credit cards and were saddled with $80,000 in outstanding bank loans and a $95,000 mortgage. In their bankruptcy filing, the Spiers’ company, which they founded in 1987 and named the Agency for Investigation and Protective Services, was deemed of “no marketable value.”

Although their circumstances looked dire, the Spiers were about to become millionaires. By May, Barbara Spier had filed the paperwork to form a new corporation called US Protection and Investigations. Soon, thanks to the contracting sweepstakes that was the war in Afghanistan, she was signing an $8.4 million deal with the Louis Berger Group. The multinational construction and engineering company had landed a $214 million contract to rebuild Afghanistan’s infrastructure—roads, water and sanitation, power and dams—from the United States Agency for International Development (USAID). USPI’s job was to provide security for contractors repairing a 300-mile road stretching from Kabul to Kandahar.

Much of the work was to be done in remote and dangerous territory, prone to sporadic Taliban assaults and blighted with unexploded Soviet-era ordnance and land mines. “Sections of the Road are subject to hijackings, robberies, and killings,” Berger acknowledged in its contract with USPI. “Organized terrorist groups are operating within the Road corridor environs, and expatriates have been intentionally targeted in recent incidents.” Safeguarding the hundreds of contractors working on the road, the construction conglomerate warned, would be “challenging.”

Given the stakes of the project—key to the effort to stabilize Afghanistan—USPI was a strange choice. Berger could have turned to a well-established security outfit with deep experience in conflict zones. Instead, it handed a noncompete contract to a firm with no reputation to speak of and a freshly bankrupted management team.

For the Spiers, the Berger windfall engineered a life-changing turnaround. And they might have lived happily ever after, too, except for one thing: They were defrauding the government, according to the Justice Department, filing phony receipts and billing for ghost employees to bilk millions of dollars from programs aimed at rebuilding the country’s war-ravaged infrastructure. (The case will go to trial in September.) Their alleged exploits, many of which have not previously been reported, offer one of the most vivid pictures yet to emerge from Afghanistan’s Wild West contracting bonanza.

Tales of epic fraud—of double billing and bid rigging, of kickbacks and theft—have dogged the reconstruction efforts in Iraq and Afghanistan. Not only are taxpayers unwittingly enriching fly-by-night contractors, corrupt officials, and local power brokers, but unscrupulous operators are undermining the prospects for progress that US troops have given their lives to make possible.

And it’s proven very tough to stop them. In Iraq, despite great efforts to improve accountability, investigations and audits have barely scratched the surface, Stuart Bowen, the special inspector general for Iraq reconstruction, has acknowledged. Afghanistan has received even less scrutiny. In conflict zones, it’s always difficult to weed out fraudulent invoices from legitimate expenses, to discern patronage contracts from necessary ones. Afghanistan’s cash-based economy, primitive infrastructure, corrupt government, and deteriorating security situation make it exponentially harder. With oversight woefully thin and auditors scarce, the bombed-out country has been a Disneyland for profiteers. “It’s just a shame,” says a former Louis Berger official. “That money should have gone towards the development of Afghanistan rather than into people’s pockets.”

Payoffs and Warlords: “Loyalty Is Rented”

The story of USPI’s rapid transformation from a mom-and-pop startup to a security behemoth begins in 2002, before the company was awarded a single contract. That year, Berger hired Del Spier as its security director in Afghanistan. “The program manager for Berger at the time, Jim Myers, he liked the way Del operated and he brought Del in,” says a former Marine who worked for USPI. Another ex-employee explains how USPI entered the picture: “When they needed a full-time security presence, Del was the natural choice. He was already working for Berger. He was the guy there. So Berger said to him, ‘We’re not going to put this out to bid. We’re going to give you an in-house contract.'”

A quiet man with a rugged demeanor, a thick Texas drawl, and the cowboy boots to match, Del, who’s 73, told his employees stories of working as an intelligence operator during the Vietnam War for Air America, the CIA-run airline. In the early ’90s, when he was heading a company called Del Spier & Associates, he’d worked in Algeria for Bechtel, helping to protect its employees from attacks by Islamic militants.

Barbara, who’s 59, had always handled the administrative end of things. She was a mover and shaker in Houston, active in local professional organizations. She once served as the president of the Federation of Houston Professional Women; the National Association of Women Business Owners even named her Houston’s Woman Business Owner of the Year. In Afghanistan, she took a keen interest in the plight of Afghan women.

USPI’s contract required the company to protect stretches of terrain so vast that it would have been too costly to hire enough US or expat contractors for the job. But Del had a solution. He brokered a deal with Afghanistan’s fledgling Ministry of Interior, which agreed to loan USPI hundreds of its troops—a coterie of ragtag militiamen under the command of a notorious warlord named General Din Mohammad Jurat. Accused of a range of criminal activity (including the murder of a man whose wife he wanted for his own), Jurat had been described to Human Rights Watch in 2003 as a “maniac” and “dangerous.” In 2007, Afghanistan’s then attorney general, Abdul Jabar Sabet, alleged that Jurat and his bodyguards attacked him in a botched kidnapping attempt. “His allegiance was to one entity and to one entity alone,” says an ex-USPI employee who dealt with Jurat. “That was the US dollar.”

In an arrangement that would have far-reaching consequences, USPI essentially partnered with the former Northern Alliance commander, paying his soldiers a $5 per diem for performing guard duties. According to multiple sources familiar with USPI’s operations, the firm went on to cut similar deals with power brokers throughout the country—basically buying the allegiance of tribal leaders and provincial officials as the road construction work passed through terrain under their control. “If you wanted security, you had to pay off the warlord or whoever controlled that region,” says the former Berger official. In some cases, he says, militia commanders were paid simply to ensure “they’re not going to attack you.”

He adds, “There was a saying in Kabul: ‘Loyalty is rented.'” And it went to the highest bidder.

The company’s Afghan recruits were ill trained and unpredictable, according to a former USPI security coordinator. “If it came down to a firefight, they would have bailed on us,” he says. “A lot of them were kids really. I remember trying to teach them how to shoot and they had no idea how to handle an AK.” Others, he said, “were ex-Taliban, or even current Taliban, but the fact that they weren’t attacking us along the way—whatever worked for us worked.”

Employing Afghan guards may have solved the manpower issue. But it may have also worked against one of the international community’s crucial goals: demilitarizing armed factions. In 2005, the International Crisis Group reported that USPI’s hiring practices had in fact served to strengthen militia commanders “politically, militarily, and economically.” Many of USPI’s guards, this NGO said, had “used their authority to engage in criminal activity, including drug trafficking.” A former USPI supervisor told me of guards who as a side project set up roadblocks on the stretches of road they were supposed to be protecting, extorting money from passersby. The former Berger official says the situation was a catch-22. “If you don’t pay them off, they kill your security staff and your contractors,” he says. “If you do pay them off, it exacerbates the problem for the future.”

Yet as risky as this relationship may have seemed, the deployment of Afghan guards, overseen by US and international security coordinators employed by USPI, became the firm’s business model—and a lucrative one. Building on its foundation with Berger, USPI drummed up contracts with the World Bank, the Japan International Cooperation Agency (that country’s version of USAID), the United Nations, and a range of private businesses, including local banks and hotels. In September 2004, it won another USAID subcontract, via Berger, this one worth more than $20 million. Eventually, USPI provided security for Berger’s entire Afghanistan operation.

By 2006, USPI claimed to employ more than 3,000 Afghan guards, along with 160 US and expat employees, and had a significant presence throughout the country, especially in Kabul, where guard shacks bearing its logo were a common sight. “It basically grew into a monster,” the former Berger official says. On its website, the company described itself as “the foremost private security company working in support of Operation Enduring Freedom in Afghanistan.” Its stated goal? To “help bring about change and improvement for the people of Afghanistan.”

Without question, USPI’s role in Afghanistan had brought about change and improvement for the Spiers. In Kabul, they took up residence in a luxurious compound that some of their employees jokingly called the “marble palace.” In their bedroom, an ex-employee adds, was a safe that sometimes contained upward of $1 million cash, used to bankroll USPI’s operation.

The former USPI security coordinator told me, “I remember at one point seeing boxes of cash that they were bringing in. I thought, ‘Wow, that’s really fucking weird.'”

Accounts Deceivable: “They Were Double and Triple Billing”

On August 28, 2007, Afghan police, FBI and USAID agents, and Blackwater contractors descended on USPI’s Kabul offices, weapons drawn. “Have you ever seen a dynamic entry, where people are clearing rooms out with guns locked and loaded and shoving a gun in your face? That’s the way Blackwater did their entry into the house,” says a former USPI supervisor. Agents seized computers and contraband weapons and carted off bags full of company records. Meanwhile, federal authorities were executing a search warrant at USPI’s Texas headquarters. Since 2005, federal investigators had quietly been amassing evidence that USPI had defrauded the US government in connection with its USAID subcontracts. Now they were making their move.

Suspicions about USPI’s business practices had been circulating through USAID’s Afghanistan operation since the fall of 2004, according to Patrick Fine, who took over as the agency’s mission director that July. “There wasn’t anything obvious that made it look like there was obvious corruption there,” he says. “My recollection is feeling from just a business point of view, feeling uncomfortable about our ability to verify the bills that we were getting. So you get a bill and it says they’re employing 250 guys in a certain sector, at $5 a day. My recollection is of saying, ‘How do we verify that this number of people actually worked for this number of days?’ It was that kind of question being raised by USAID, by the project managers.”

He continues, “That led us to ask questions like, ‘Is there some system that you can audit to see that they’re actually delivering what they say they’re delivering?’ As soon as USAID had some suspicion that there might be something awry in the business practices, we brought in the inspector general. There wasn’t any delay or dithering there.”

The resulting investigation confirmed Fine’s concerns, and then some. The search warrant application seeking permission to carry out the Texas raid noted that USPI’s initial Berger contract, awarded in June 2003 for $8.4 million, had ballooned to $36 million by August 2005—and it outlined a host of allegations pointing to the potential cause of some of those overruns. Investigators said they’d “obtained evidence showing that USPI deliberately and systematically created phony receipts and invoices to justify the billing of millions of dollars in expenditures for which USPI did not have supporting documentation.”

An audit by accounting firm A.F. Ferguson & Company of USPI’s billing records between June 2003 and March 2005 had turned up $17 million in costs that lacked “adequate documentation,” and another $160,830 in charges that were deemed ineligible. “Officials for USPI initially claimed not to have most of the supporting documentation for the $17 million in questioned costs,” according to the warrant application. “However, they later provided receipts and invoices to support the billings.” These records, investigators determined, were fakes: “Government investigators learned from a witness that he, with the assistance of other USPI employees in Kabul, Afghanistan, and with the knowledge of Del Spier…witnessed and/or participated in the fabrication of receipts and invoices to support the $17 million in questioned costs.” To make the invoices appear authentic, the USPI employee said, he and other employees were directed to deposit them in a warehouse where the company stored fuel.

There was more: Another USPI employee “stated that only about 50 percent of the guards for which USPI billed LBGI actually existed” and that Del Spier regularly overbilled for personnel. Not only were personnel records fabricated, this source said, but Del’s executive assistant, an Afghan named Behzad Mehr, routinely created fake invoices from nonexistent companies for fuel and vehicles. According to one USPI informant, Bill Dupre, the company’s operations manager in Afghanistan, instructed new employees to inflate costs in order to cover expenses like office supplies, ammo, and other items: “You were to put an extra 10 or 15 guards on the payroll that did not exist.” The government alleged that “Del Spier knows about all these activities.” It also claims that Barbara had been involved in the fraud as well, and had even been caught trying to deceive a federal auditor about invoicing Berger for an employee who was no longer working for the company.

After the raids in Kabul and Texas, the investigation churned on for more than a year. Then, in early October 2008, the feds swooped in, arresting Del and Barbara Spier in Texas and Bill Dupre in California. Also named in the indictment was Behzad Mehr, though a release issued by USAID noted that Del’s right-hand man “remains a fugitive.” (Several sources told me that Mehr was in fact imprisoned in a Kabul jail at the time, and he remains there today.) The four were hit with multiple fraud counts, charges that together carry prison sentences of up to 35 years and fines of as much as $1.5 million.

The indictment cites additional evidence of fraud, including a May 29, 2005, email exchange in which Mehr had requested Del Spier’s permission to insert addresses and phone numbers on fabricated invoices. Not only did Del direct him to do so, the indictment states, but he also told Mehr “to obtain office space in the event that LBGI requested to see the companies’ offices.” According to court records, templates used to create phony invoices were discovered on computers belonging to Mehr and Barbara Spier. Image files containing the scanned signatures of MOI officials, presumably used to make invoices look genuine, were also recovered.

“They were double and triple billing for soldiers and screwing the contract on rental cars,” a former USPI employee told me. “If they were renting a car for $750, they’d bill USAID $1,500. If they had 1,000 soldiers working, they’d get 3,000 thumbprints on the pay sheets and submit it.” He adds, “These were the kinds of things they did.”

Kabul’s Wild West: “We Were Our Own Little Warlords”

There were plenty of warning signs, says Steve Appleton. A retired colonel in the Canadian army, Appleton took over in June 2005 as the manager of road construction projects in Afghanistan for the United Nations Office of Project Services. UNOPS had received a $35 million USAID grant to build a network of secondary roads throughout the country. This work might have gone to Louis Berger, had its own projects not been vastly over budget. (The price tag of its $214 million contract ultimately climbed to more than $700 million.) “There was no more appetite” to make Berger the prime contractor, Appleton told me recently from Kabul, but USAID still made sure Berger got a piece of the action. The agency stipulated that UNOPS had to subcontract out the engineering aspects of the job to Berger. And with Berger came USPI.

Early in his tenure, Appleton began to hear grumbling about USPI from a variety of sources: Berger employees, members of the UN’s security branch, USAID officials, and other security contractors. Not only were there complaints about the accuracy of the firm’s accounting practices, but there were serious criticisms of USPI’s performance of its core mission: protecting the vital work of rebuilding Afghanistan.

According to Appleton, “USPI was absolutely detested by Afghan civilians” and had developed a reputation for being “very aggressive and very cowboyish.” Among other things, he says, “They would fire before they would see where the firing was coming from. They would put down spec fire. That was just unacceptable.” (Patrick Fine, who no longer works for USAID, had a different take: “They seemed to be doing their job,” he says. “I never had a performance issue with them.”)

The former USPI security coordinator says there was little management or oversight of the company’s employees in the field. He found the company totally disorganized, its management secretive. “They kept so much stuff in the dark,” he recalls. “I never signed a contract with that company,” he adds. “I was thrown into it. Here’s a bulletproof vest, here’s a couple of grenades, here’s an AK.” Like a mafia payout, his $600-a-day salary came in an envelope jammed with cash. “There was a lot of cash going around,” he says.

He and other ex-USPI employees tell of being dangerously underequipped, issued faulty weapons and Land Cruisers that would frequently break down on perilous stretches of road. “I was really thrown out there… without any proper gear. They didn’t care, Del and Barbara.” It wasn’t until he went out to take target practice one day that he realized his USPI-issued AK-47 was broken. “It would only do single shot. I had to cock it every time I fired it. I thought, ‘Holy fuck, thank god I didn’t get in a firefight, because it would have been over really quick.'”

The equipment situation got so bad that at one point he was forced to take matters into his own hands, leading a raid on a one-time Taliban weapons depot in order to secure RPGs for his men. (“I found a Conex box filled with Russian RPGs still in the plastic.”)

Berger contractors and subcontractors would complain bitterly about USPI. “I personally did not find them very professional,” says Danie Steyn, an engineer who worked on Berger’s road projects. “As a matter of fact, some individuals were acting like prima donnas, and considered themselves untouchable.” At one point, he says, a complement of USPI’s Afghan guards left him “stranded next to the road” without protection “while they set off to pray.”

Such incidents weren’t unusual, says the security coordinator. “Louis Berger was always complaining to us,” he says. “Our guards would just take off, leave them in the middle of nowhere. I’d get sat phone calls saying, ‘Where the fuck are the guards! We’re out here in the middle of nowhere by ourselves!'”

According to the former security coordinator, whose account is supported by a variety of wire reports, USPI’s guards were taking heavy casualties. “USPI lost a lot of guys,” he says. “We were out in the desert getting pretty much executed.”

“The operations were so hands-off,” he adds. “They stuck people in bad places, and you had to do what you had to do to make sure you didn’t get killed.” He continues, “We were our own little warlords over there. We did our own thing. I could have shot a guy in the head on the side of the road and nobody would have said a thing.”

Guarding USPI’s Interests: “You Just Didn’t Mess With Their Contract”

In September 2005, one of USPI’s American employees did shoot an Afghan in the head—a 37-year-old named Noor Ahmed who worked for the firm as a translator. Although the incident landed the company briefly in the news, the identity of the shooter has never been previously reported. Two former USPI employees told me it was an ex-Marine named Todd Rhodes. (Rhodes was killed in Iraq in August 2006 while working for the private security firm Cochise.) The former USPI supervisor insisted the shooting was justified, that Ahmed “drew down into a firing position on him and Todd shot him in self-defense.” Yet questions remain about the shooting and whether it was fully investigated. While the ex-USPI supervisor says Afghanistan’s Ministry of Interior “did a quick investigation” and cleared Rhodes of wrongdoing, the company spirited him out of the country before a formal probe could be launched. The provincial police chief has said he sent a team to USPI’s compound to investigate but was barred from entering by the company’s guards.

The incident only fueled Appleton’s concerns. He decided to see about severing USPI’s relationship with UNOPS—its contract was due to expire later that summer anyway. USPI could rebid for the work, but Appleton was determined to find the company best equipped to keep contractors safe. In the end, he says, “USAID balked,” convincing him that UNOPS should extend the contract for another three months while the security situation was reviewed. (USAID did not respond to a detailed request for comment.)

“All the while we were getting smoked out there in terms of casualties and fatalities on the roads project,” Appleton says. “I don’t think anyone’s ever come clean with what the numbers were. We had more casualties than US soldiers in Afghanistan in 2005 and 2006. We were getting creamed. We had international security coordinators with USPI getting beheaded. We had Turkish contractors getting wiped out. We had Afghan security guys in the employ of USPI getting smoked. It got so bad that I led a group with LBG to contact the US Embassy to say, ‘You’ve got to better arm us because we’re getting creamed out there.'” He adds, “USPI had adopted a real cowboy approach with regards to, ‘Bring ’em on. We’ll create the peace by simply killing enough of them.'”

Appleton tried again to cancel the contract. Eventually several security companies, including Aegis, a well-regarded British firm, were approached about taking over the task. But before very long, Berger resisted.

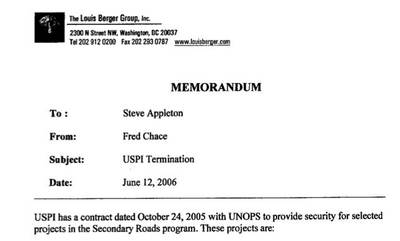

In June 2006 Fred Chace, then Berger’s deputy operations manager in Afghanistan, sent Appleton a memo recommending against removing USPI from the project.  (Mother Jones obtained a copy, and Appleton confirmed its authenticity.) The memo (“Subject: USPI Termination”) lays out myriad criticisms of the company’s work. “Over the course of the project, USPI has continued to be non-responsive to the needs of the Employer,” Chace wrote. “The primary complaint with USPI is the failure of their Kabul management to support their field security advisors and to comply with the requirements of UNOPS in regard to reporting and other administrative functions…UNOPS has also expressed its concerns over the ability of USPI to assure that their security force has a sufficient supply of ammunition to fight off any attack on the projects.”

(Mother Jones obtained a copy, and Appleton confirmed its authenticity.) The memo (“Subject: USPI Termination”) lays out myriad criticisms of the company’s work. “Over the course of the project, USPI has continued to be non-responsive to the needs of the Employer,” Chace wrote. “The primary complaint with USPI is the failure of their Kabul management to support their field security advisors and to comply with the requirements of UNOPS in regard to reporting and other administrative functions…UNOPS has also expressed its concerns over the ability of USPI to assure that their security force has a sufficient supply of ammunition to fight off any attack on the projects.”

Chace also noted that “one of the criticisms of USPI has been their ragtag MOI soldiers,” but raised concerns about cutting off the warlords that USPI was dealing with. “Considering the probable flow of the money, it would be a security risk to the project…if they did anything that disrupted that flow of money,” he explained, adding that for this reason Aegis had also proposed using MOI guards, as well as members of the Afghan National Police. Chace, who declined an interview request, acknowledged in the memo that Aegis “is an experienced and qualified firm. There is no doubt about that.” But, he concluded, “It does not appear that there is any economic benefit to changing security providers; in fact it could cost the program up to $900K more…We are not convinced that this transition could be made without any initial impacts that could jeopardize the security of the staff and result in further damages by the possible suspension of the work due to a decrease in security until Aegis is up to force.”

Appleton had hit a brick wall. He was puzzled. “It was just a mom-and-pop organization out of Texas,” he says. “These guys were amateurs. It just didn’t make any sense.”

But Appleton believes he finally discovered why Berger officials were so reluctant to tamper with USPI’s contract—and why Del Spier and his company may have landed the work in the first place. Once, Appleton asked Berger officials why USPI was hired. “The answer I got back was that Jim Myers and Del go way back,” he says. Myers was the engineer in charge of Berger’s Afghanistan operation, and the official who worked most closely with USPI. “Jim Myers was a 100 percent supporter of USPI and Del,” explains the former Berger official. “He wouldn’t accept criticisms of them. Certainly, he would never have entertained—ever, ever—removing USPI. Ever, despite anything. You just didn’t mess with their contract.” He continues, “It was just understood that there must have been a relationship between USPI and somebody in Berger, or Jim. That was just the way it was. That was the only logical reason why that would be in place…It was a relationship issue.”

Other sources told me that Myers and Del Spier had a long-standing friendship. “It was all very incestuous,” says an ex-USPI employee. Confirms the former supervisor, “They have a very close relationship.”

(When I reached Myers, who retired in 2007, at his home in Northport, Washington, he repeatedly denied having any history with USPI’s founders. Moreover, he insisted that his relationship with Del was “no more friendly than with any other subcontractor. I worked with all of them.”)

“How far back it went into the halls of LBG, I don’t know,” says Appleton. “But the running joke in Kabul when Del and Barbara Spier got arrested was that all the executive officers’ doors at LBG were slamming shut.” It appears that Del and Barbara are chummy with other Berger honchos, too. Just last February, Fred Berger, the chairman of the Louis Berger Group, attended a fundraiser in Houston for the American University of Afghanistan, of which he’s a founding trustee. Also in attendance were the Spiers, and Berger made a point of introducing his guest to Del and Barbara. (The Louis Berger Group did not respond to a detailed request for comment, citing the ongoing criminal case.)

Even some of the company’s own employees wondered why USPI had been trusted to protect hundreds of millions of dollars worth of infrastructure projects, and the lives of the men and women building them. “In terms of how they got in, it didn’t make any sense,” the former USPI security coordinator recalls. He says he at first “figured they were pretty well established. It wasn’t until I went online and googled them and saw their website looked like something an 8 year-old made on Microsoft Front Page that I was like, ‘What is going on?’ That just kind of blew me away. But I figured, ‘Well, they got these contracts for some reason.'”

Appleton places part of the blame with USAID for allowing Berger to hire USPI in the first place. “Why USAID would even want to do that when there was so much at stake is mind-boggling.” I asked Patrick Fine, the former USAID official (who, like Appleton, inherited USPI’s services), why the firm had been allowed to take on such a critical task. He responded by describing the strain of operating in post-invasion Afghanistan. “People just don’t understand unless you’ve lived through it the kind of pressure to deliver results,” he told me. “In this case to get that road built under difficult circumstances in a very short timeframe. Expediency becomes the driving force.”

Fraudsters of the Reconstruction: “It’s Endemic”

By now, things have come full circle for Del and Barbara Spier. They lifted themselves out of bankruptcy and struck it rich, only to wind up in jeopardy of losing everything once again. In February, the Justice Department filed a complaint seeking to seize the half-million dollar Hempstead, Texas, home the Spiers purchased in 2005 partly with proceeds from the alleged fraud scheme. Their passports have been taken away, and they must gain permission to leave the state of Texas. USPI wrapped up its last USAID subcontract this winter, shortly after the firm was placed on the federal government’s Excluded Parties List. This designation precludes the company from receiving any government work pending the outcome of the criminal case, which goes to trial in late September. (The Spiers and their lawyers declined interview requests.)

But USPI remains very much active in Afghanistan, with the Spiers calling the shots from Texas. A recent visitor to Kabul told me of seeing USPI’s guards posted at a variety of restaurants and local businesses. “As things are getting more dangerous, they’re getting more business,” says the former Marine who worked for USPI and who remains in touch with Del Spier. But Appleton, who now runs his own consulting firm focused on strengthening Afghan businesses, says the company is hardly the player it once was. “They’re doing the rinky-dink jobs now, a restaurant here and there. They’re not nearly as pervasive.”

Though the Justice Department appears to have a strong case, some USPI alums remain fiercely loyal to their former employer. “Del Spier would have fired anyone in a heartbeat if he found out that anyone was ripping him off and ripping the government off,” says the former USPI supervisor. “From what I know of Del, he tried to do an honest job over here.” He blamed the charges on a “vendetta” by the lead USAID investigator in the case—which also appears to be part of the strategy the Spiers’ attorneys are employing—while at the same time suggesting that Del’s assistant, Behzad Mehr, may have “jury-rigged the numbers.” He adds, “This is killing Del.”

If the Spiers, along with Bill Dupre, are found guilty of fraud, it’s likely their case represents one small chapter in a much larger story of reconstruction-related corruption in Afghanistan. Almost everyone I spoke with for this story told of a culture of graft so pervasive in the country that payoffs and kickbacks are considered part of doing business. “Any company over there, when you hire local Afghans, they’re all on the take,” Myers told me. “Every goddamn one of them. When you look at it in retrospect, you can’t really blame them. Hell, they never made any money in their lives. So if they’ve got a chance to rip somebody off, they’re going to do it.”

It’s not just the Afghans, of course. Amidst the chaos of war and insurgency, foreign contractors and others have surely siphoned off a share of the reconstruction money pouring into the country. Even members of the military have attempted to parlay the absence of oversight into a payday. In mid-June, two Army officers who served at Bagram Airfield pleaded guilty to charges of fraud and bribery for accepting kickbacks in exchange for steering work to contractors.

“It’s just endemic,” says the former Berger official, adding that many of these schemes were “hiding in plain sight.” For instance, he says, he knows of people working on reconstruction projects who received several hundred thousand dollars in bribes from subcontractors. “They were the ones who had to sign off on the quantities, on the number of vehicles, on the invoicing,” he says. “The contractor puts in a false invoice, they pay off the guy, the guy certifies it and submits it to USAID. No one’s the wiser. The contractor makes money and the guy supervising it makes money.” Laughing ruefully, he adds, “They bought a small plane for one of them. A small plane.”

The fact that opportunists have enriched themselves off projects that were intended to lay the foundation for a stable Afghan society makes this all the more tragic, he says. But he thinks that perhaps there’s a lesson to be taken away from all of this—from USPI’s story, from Afghanistan’s flawed reconstruction. “Everyone’s accountable in the end,” he says. But there’s a big difference between being accountable and being held to account. The latter comes only after you’ve been caught.