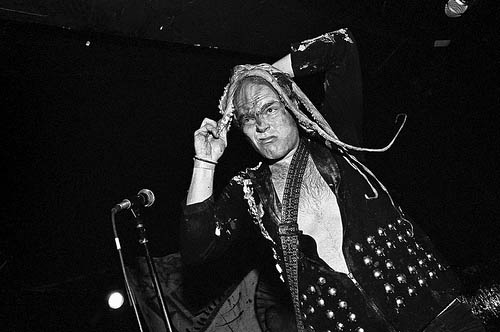

Photo used with permission from Pirate Cat Radio

At age 15, Daniel K. Roberts, better known as Monkey Man, built a radio station in his bedroom at his parents Los Gatos, California home using a 40-watt transmitter, a mixer, a tape deck, a portable CD player, and a microphone. That was 13 years ago. Monkey’s pet project eventually became Pirate Cat Radio 87.9 FM, a cafe, community outlet, and unlicensed low-power FM radio station that served San Francisco for more than a decade. In August 2009, the Federal Communications Commission fined Pirate Cat $10,000 and ordered it to either get off the airwaves or face further fees. Here was a subversive station that didn’t rely solely on a cool record collection or a standard corporate algorithm to garner street credibility. For now, it’s been relegated to Web only, and Monkey has been busy fighting the feds for the right to get back on the air while local music venues host fundraising events to help pay off his fine. I bussed over to the station’s not-so-secret heaquarters to ask Monkey about the state of his operation, and whether Hollywood got the pirate radio story right.

Mother Jones: You’ve said that you don’t want to piss off the FCC. Why not just get a license?

Monkey Man: You can’t get a license. It’s $2 million to get a license. Actually, no, it’s now $6.5 million for the cheapest license sold in the Bay Area and that was for the license for what was on Energy 92.7.

MJ: So it’s the cost that’s preventing you from complying with the FCC?

MM: The cost is one thing. The current rules are another thing. If four frequencies around one are open, then you can get a license for it. (See “Low Power to the People.”) Obviously in a place like San Francisco, where there’s only 200 channels in a spectrum, you’re just bombarded by radio stations; there’s never going to be a frequency that has two adjacent frequencies open. It’s unrealistic.

MJ: Do you think everyone, regardless of whether they can afford a license, should be able to start a radio station?

MM: I think it should be easier for people to get licenses. I think it’s unrealistic to have these megastations putting out 12,000 to 20,000 watts. There should be more emphasis on clearing the way for individual communities to have licenses to serve their areas versus these monstrosity radio stations that cover a whole area. KCBS alone covers not just Northern California, but I was on a road trip a few weeks ago and I could hear them all the way into Phoenix, Arizona. How is making a San Francisco-based radio station broadcast all the way into Phoenix and everything in between worthwhile? I don’t see the purpose. In Germany they have a great system set up where community radio licenses are given out to people who want to have community stations, and they’re given out for short periods of time. You have two years to utilize that license and at the end of two years it goes up to auction again and another organization is able to take that license and do something, and it just keeps flipping over that way. I think a system like that is brilliant, and maybe something that should be implemented here. If not, allocate specific frequencies within an area to be used just as community radio stations.

MJ: Has Pirate Cat ever broadcast a message that affected local politics?

MM: Last year with the presidential election, there were various supervisor elections in San Francisco. I think we were the only radio station that actually held three different supervisor debates. Our door was open to anyone from the public who wanted to come in and sit down, watch all the candidates debate, and ask them questions. Also, a few years ago, the voters said they didn’t want to have box stores coming into San Francisco, or large chain stores. American Apparel was coming to move into the Mission district and a lot of people really didn’t know what to do about it or how to proceed. So we held protests and live broadcasts out in front of the retail space that it was supposed to move into and got something like 3,000 signatures and kept people informed about when the Planning Commission meetings were happening, and just annoyed the commissioners because their chambers were bombarded by people who were opposed to American Apparel. It’s not a huge battle, but it’s one thing I can think of where we were actually able to get a lot of people together and organize them. Not just inform them.

MJ: So Pirate Cat Radio has a political agenda?

MM: No, it’s more of a social experiment. It’s seeing how the public responds to having a radio station that’s open, that they can come participate with at any time, and giving DJs and people from the community the space to actually do the radio shows that they want to. I think that having a specific political message or political agenda would be too biased and slant things. It’s my responsibility to keep Pirate Cat Radio open to all opinions, whether that’s centrist or liberal or conservative.

MJ: Have you changed your programming, besides moving solely to the Web, as a result of the fine?

MM: There’s nothing to change. We’re not telling people to make Molotov cocktails or something. We’re just trying to unite people and bring them together to have a voice and an information source. But the reason the FCC is possibly giving us a fine and telling us to get off the air, I think, is not because of content or because of interfering with other stations. The FCC just licensed outside of the filing period for TV channel 6 in Fremont, which utilizes 87.9 FM for its audio carrier, so I wouldn’t be surprised if somebody with a big pocketbook said, “Hey! We want this license and we’re going to pay you money to give us a license outside of your filing period. (By the way, who are these guys? Get them out of the way.)” That’s all just speculation, though.

MJ: Why fight for the right to be on the radio when it’s practically obsolete?

MM: A lot of people don’t have the money to spend to be a part of the digital world. They don’t own a computer. They don’t have an Internet connection; if they do have an Internet connection and computer, they can listen to Pirate Cat Radio online, but they still have to deal with buffering and not having the right software to listen to the stream. Whereas when a radio station broadcasts through analog air, you can go and pick up a radio at Radio Shack literally for $5 and turn it on, tune to 87.9 FM, and you’ll get Pirate Cat Radio.

MJ: Who’s listening and how do you know they are?

MM: Our metric is one that a lot of other radio stations follow based on the power being put out; for every phone call you get there’s about a hundred people listening. In addition, we have over half a million downloads to our podcast every month and unique individual IP addresses downloading those, then something like 36,000 unique IP addresses listening to the online stream at any given moment.

MJ: You often cite a specific federal provision for its protection of unlicensed stations during wartime. Were you aware of this loophole before you started broadcasting in 1996?

MM: Not until 2002. All it is is that if Congress or the president declare war, it’s our civic duty to keep communications with each other by all means possible. So in order to do that, you have to fill out an informal boilerplate application and send that to the FCC. So I did that. Every time the transmitter was on the air, I would write up one of these applications and send it to the FCC, but also give them a check for $5 or $10. And they took my application—didn’t deny me, didn’t accept me, but they did take my money every time. I have over $100 in checks that have been cashed by the FCC for these applications. That would happen basically every quarter for awhile. They would give us a notice saying that you have X amount of time to turn your transmitter off, and I would always respond back with one of these applications.

MJ: What is it about the current licensing system that makes stations so disconnected from their local communities?

MM: Licenses now have become more like real estate; the more successful you make a radio station around a specific license, the more you can later sell that for. If that’s your goal, to make money off of radio, so be it. Go and do it. But I don’t think the staff at Pirate Cat Radio has the goal of having a radio station that’s going to make $7 million a year. It’s a matter of just getting the voice of the community out.

MJ: How much does it cost to run Pirate Cat?

MM: I started this place, as far as the café and the studio that you see here, with a little over $8,000 out of my own pocket. I had a lot of great people get together and help build everything out, just out of charity basically, and the fact that they love Pirate Cat Radio.

MJ: How much revenue does it bring in?

MM: The café basically pays our rent. Our rent here is $1,300 right now. The DJs’ station dues pretty much pay the electricity costs and supplies for operating the café. It’s all sort of symbiotic.

MJ: How much are your attorney fees?

MM: Two hundred and twenty dollars an hour.

MJ: Have you ever watched Pump Up the Volume with Christian Slater?

MM: It’s a really cute film. Unfortunately, it’s very unrealistic. Kind of like the Pirate Radio film that just came out.

MJ: What doesn’t match?

MM: The FCC doesn’t drive yellow vans. They look like this guy sitting on the couch over here. [He points to a man in a polo shirt and jeans.] They drive Toyota Corollas and take pictures from their cars. They’re not obvious.

MJ: Have they driven by recently?

MM: The Notice of Apparent Liability for $10,000 that they gave us says that they had people observing us by sitting in vans outside and coming in and ordering coffee. They would actually come and sit in here and watch everything for the whole day pretending to be doing something else.

Click here for more Music Monday features from Mother Jones.