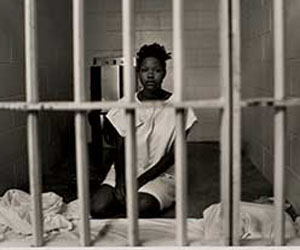

Flickr / <a href="http://www.flickr.com/photos/publik16/2570753935/">publik16</a>.

Editor’s Note: Last November, the Department of Justice released the results of a federal probe into conditions at Westchester County Jail, a 1,693-bed adult facility in Valhalla, New York. Among the litany of problems investigators cited was the ease with which jail officials seemed willing to toss juvenile inmates into Westchester’s so-called special housing unit. They found that half of the inmates recently consigned to the SHU were 16 to 18 years old, and many were doing stints of a year or more in isolation. One 16-year-old got 510 days for assaulting a guard. Another teen, an 18-year-old, was simply thrown in the SHU indefinitely. “Such sentences,” the report noted, “may inflict substantial psychological harm” on juveniles.

For author David Chura, the findings were no revelation. Chura had served his own 10-year sentence at Westchester as a high-school English teacher, schooling young inmates under the most difficult circumstances. He chronicles these experiences in I Don’t Wish Nobody to Have a Life Like Mine: Tales of Kids in Adult Lockup, out this month from Beacon Press. In this excerpt, Chura recalls his first glimpse of the special housing unit, and how first impressions can be deceiving. —Michael Mechanic

(The following excerpt adapted by permission of Beacon Press. Copyright 2010 by David Chura.)

The only thing missing was the ribbon cutting. Other than that, our first glimpse of the Westchester County Jail’s special housing unit—its gleaming new isolation block—had all the trappings of a grand-opening celebration. There were the distinguished guests, the fancy pastries, the bottled water, and freshly brewed coffee.

The county exec was saving the whole ribbon routine for the media, and we were just a bunch of civilians—medical staff, teachers, and clergy who toiled at the older facility.

“I hate civilians!” Warden Clooney had barked during an orientation session on the first day of my 10-year stint teaching young men locked up for everything from trespassing to murder.

These weren’t just “at risk” kids. They were the risk. To themselves, their families, their girlfriends, their enemies, the towns they lived in—to the whole goddamn society. At least, that was Warden Clooney’s take. “Human garbage,” he reminded us repeatedly. And he could say whatever he pleased: “I’m finally retiring after thirty years, getting out of this shit hole.”

Indeed. It was Warden Root, one of Clooney’s successors, who presided over our tour of the isolation unit. Root, the man in charge of the new construction, was young for his title, and he didn’t take most things too seriously. But he was dead serious about the SHU.

Around a large mahogany conference table, we were treated to back-slapping speeches, charts, and color-coded graphs, as well as a publicity folder in which we read that the SHU was built specifically to handle the most dangerous and disruptive inmates. Everything was designed, we were told, to ensure their safety—and ours. “People will be coming from all over the country to see what we’ve done here,” he told us, suddenly solemn.

As we followed Warden Root down the penitentiary hallway, we cracked jokes about how we looked—and felt—in our obligatory hard hats, laughably mislabeled “one size fits all.” The nurses complained that the yellow helmets clashed with their colored smocks, and we teachers quipped that we might be needing them in class. Father Gabe, one of the prison chaplains, confessed that he kind of liked his—it made him feel like Father Mulcahy from M*A*S*H*.

We grew louder and sillier than we ever would think of being during our regular workday. But once we made it past the SHU’s first security gate, waiting in the sally port for the other door to open, we fell silent. The light was muted, the walls were freshly painted a pastel blue, and the air was cool and clean. Slowly, we could feel the noise, tension, and chaos of the rest of the jail slipping away.

When the second glass-and-metal door slid open, we stepped into a hallway next to a high-tech control desk and stared down two long, cell-lined corridors at right angles to each other. The cement-block walls were a smoky gray, the tiled floors glossy with wax, the lights recessed and fluorescent. And even though the block was unoccupied, no one spoke above a whisper.

Conspicuously absent were the constant clankings and gratings of the main jail’s barred gates and nerve-jangling PA system, with its nonsensical announcements and static feedback. If you held your breath, which the place made you want to do so as not to disturb things, you could hear the faint swish, swish, swish of an ultramodern air system.

“Each cell is monitored visually here on this panel,” said Warden Root, pointing to the control desk’s glowing mini-screens. Inmates could communicate with the officer on duty via intercom.

“The hallways are also equipped with cameras and wired for sound.” Root pointed to various corners and ceiling openings. “So watch what you say,” he added, impishly.

The cells were positioned so that inmates couldn’t see each other, and the glass fronting each cubicle was as thick as the maroon steel beams that framed it. Each door had a slot for food trays, but even that had a hinged metal flap lockable from the outside.

“Any of you who’ve worked in the old jail, especially with the minors, know the different kinds of mischief inmates can get into,” Warden Root explained, unlocking a cell door. “You know the type of thing I’m talking about: the stuffed-up toilets, the faucets going full blast so the block gets flooded. Hitting each other with telephone receivers. Taking the showerheads apart and using the metal pieces for weapons.” It was a litany we’d heard before.

“Not to mention what they do with their feces.” He screwed up his face like a parent changing a messy diaper. “We’ve addressed all those safety and security issues here.”

Root swept his arm across the cubicle like a real estate agent. “An inmate never needs to leave his cell except for visits and court. And even then his arms and legs are shackled, and he’s escorted by two officers. He eats, showers, sleeps, and does the other s word right here.

“The showerhead is set into the wall so there’s nothing to take apart,” he said, running his hand over the smooth surface. “His shower is turned on and off by the officer at the control desk, and his toilet is flushed the same way.

“Each cell is equipped with a phone. That way an inmate doesn’t have to leave the holding area to make legal or personal calls.”

Here the warden paused and watched us scan for signs of a telephone. He smiled, pleased with himself. Then he moved over to the wall at the foot of the bed and pointed to two small grates flush against the concrete. “One’s an earpiece, the other’s the mouthpiece. Simple, eh?

“Numbers are dialed by the officer and calls are terminated by the officer.”

He shrugged. “Sometimes you got to do that, help a guy out of a tight situation by hanging up the phone for him when he’s getting all crazy with his girlfriend, or his moms, or his lawyer.”

Root moved along to a sliding metal door in the cell wall. “As you all know, state regs mandate that a detainee must have at least one hour of rec per day,” he said. “But the SHU inmates are lucky. They can have as much rec as they want.”

He pressed the cell’s intercom button and the door clanked open. The adjoining cubicle was no bigger than the inmate’s living quarters, but it seemed that way without the standard sleeping pallet, sink, toilet, and shower cubicle. The rec room, in fact, was entirely empty: no equipment, no workout mat—just a concrete floor.

You couldn’t see much through its mesh-covered windows. Not that there was much to see: some high-tension power lines and a torn-up field. But there was a grate at the top of the wall that opened to the sky; its sunlight and fresh air provided a semblance of freedom.

“Any questions?” The warden scanned the group.

No one said anything, so we all moved out of the cell and toward the exit. The warden shook each of our hands as we left. “Come back and see us real soon,” he quipped.

After the tour, I had a hard time thinking of the SHU as a punishment. On the regular cell blocks, the noise and smell were assaultive and relentless. As soon as you walked through the door, it hit you, and there wasn’t any escaping it: Two televisions booming—one in English, the other in Spanish. People yelling down from the tier. Someone hollering into a phone, shouting for everybody to shut the fuck up because he couldn’t hear. The security phone ringing. The CO bellowing out names for sick call, visits, haircuts. Showers hissing and toilets gurgling.

And it stank. Forty male bodies sleeping in bunks three feet apart can’t help but smell of sweat, shit, piss, sex, and bad breath. And all the meals, no matter what was served, smelled of rancid meat and overripe fruit.

So somehow the quiet, the peace of having a cell all to yourself; air scrubbed clean by filters; floors polished; walls freshly painted; everything pristine; the sunlight penetrating your space in a system where usually nothing is “yours” and “space” only exists in your head—all of these things, it seemed to me, made the SHU appealing. It was where you would want to be, not a place the emergency response team would have to drag you into.

The first few times I visited students there—back when the SHU was still the object of pride and curiosity, even among inmates—things were clean, calm, and serene. Even Officer Saner, the CO assigned to the new post, was on his best behavior.

Usually, Saner held everyone in contempt. It didn’t matter who you were or what your rank: Inmates, civilians, other COs, sergeants, captains, the occasional warden—we were all the same to him. His disdain permanently curled his lips into a sneer, and his shaved head made him look even more imperious than he was.

But even he was under the spell of the new furniture, the high-tech equipment, and the fancy gadgets. He’d stand up when you came into the unit, greet you, and ask how he could help.

The kids I visited there went through their own transformation. They kept their cells neat. They made their beds, sheets tight and crisp. They stacked their books and magazines neatly on the high windowsills and stored their rolled up towels next to the books.

My students appreciated my visits and the materials I brought. They’d ask how I was, how class was going, how officers Ramos and O’Shay were doing. They’d thank me for coming, and hoped I’d visit again soon.

And I did, as often as I could. At the end of my own chaotic day in the classroom, I’d scoop up whatever magazines I had around—National Geographic, Junior Scholastic, Science Today—and head out to the SHU. I could feel myself decompress as I waited in the sally port.

My guys in the SHU didn’t curse or shout or rap incessantly as they did in class. Instead, they were soft-spoken. And they did something they rarely did in the classroom: They listened. They attended to what I said. They looked at me intently, as though they were reading my lips. And when it was time for me to go, they’d press their faces at odd angles against the glass so they could follow me down the hallway with their eyes.

It was only after I had been visiting the SHU for a while that I began to see things differently. At first, I thought the changes in my students’ behavior were the result of the calmer, cleaner environment.

But more and more I realized that it was, in fact, the result of their total isolation. They listened, they studied my face, they begged me to return, and they watched me leave because they were hungry—for words, sounds, the sight of people—any stimulation that broke their solitude.

In the months that followed, the SHU began to show this underbelly of deprivation. Conditions deteriorated. The walls got scuffed and nicked where inmates struggled against the emergency response teams carrying them in. Windows grew smeared from hands and faces pressed against the glass.

Gradually, the inmates stopped making their beds. They piled clothes on the floor. They left books and papers wherever they dropped. Now when I visited after class, some of my students would be sleeping. They’d bury themselves under the covers, their heads wrapped up in towels for warmth and to shut out the light.

If I was able to wake them, calling through the tray slot, they’d grumble and splutter to be left alone. Once they knew it was me and got up, they were still polite and appreciative, but they would stare, stunned and bewildered—wondering if I was real or just part of some dream.

And they were dirty. Even the guys who were usually fastidious about grooming became sloppy and disheveled. Like Pinto, who used to arrive to class every day scrubbed, shaved, and smelling of Old Spice. His county oranges would be pressed, and his hair clipped short and brushed to a black lacquer.

But in the SHU, his eyes grew puffy and crusted from endless hours of sleep. His face was covered with a patchy, scruffy beard, and his hair was knotted and woolly. When he leaned down to talk to me his breath was sour, and the odor of his unwashed clothes and body rose out of the metal opening like a malevolent genie.

Despite the modern air system, that same foul, stale smell of soiled sheets, and unwashed armpits and assholes, soon began to pervade the whole unit. It hit you as soon as you walked in. But that wasn’t the only thing that hit you when you left the sally port.

There was also the noise. Although many of the men had turned day into night, those who weren’t sleeping would be screaming. With typical jailhouse ingenuity, SHU inmates had discovered that they could communicate if they went out to their rec decks, plastered themselves against the wire mesh, and shrieked at the top of their lungs.

It might’ve been hard to distinguish the words of their fellow inmates, but that didn’t matter. One human was still connecting to someone like him, someone living with the same sense of loss and isolation. And the department of corrections couldn’t do a damn thing to stop it.

Officer Saner wasn’t far behind in his deterioration. He soon realized that once the emergency response people put an inmate in the cell, he was the gatekeeper for all of that man’s requests. All he had to do was push a button—or simply ignore the inmates’ pleas.

His helpful attitude toward me vanished. He started depriving me of teaching materials that he’d previously allowed through, claiming that they were contraband; or he would insist that the school provide supplies that the SHU had furnished before.

It got to the point where Saner barely acknowledged my presence. Protected by his bank of controls and monitors, he didn’t even bother to look up from the motorcycle magazine he was reading. Instead, he’d let me stand there for a minute or two.

Then he’d point to the top of the desk panel for me to leave the work, and flick his fingers, dismissing me. Or he’d tell me to come back at a “better time,” when he wasn’t so busy.

With each refusal, he invoked safety and security issues. “All I can recommend is that you talk to my superiors if there’s a problem. Sir,” he would snicker, knowing that none of us civilians were stupid enough to do something like that if we ever wanted to get any business done in the SHU.

Eventually, inevitably, the grand, open feel of the SHU became as closed and claustrophobic as the rest of the jail. The tours ceased, and the inquiring visitors became less frequent.

The rutted field around the facility filled up with weeds and tattered plastic bags. There was no longer talk about bringing in truckloads of topsoil and seeding it with grass, or maybe planting a few flowering trees. Warden Root was too busy. He was knee-deep in blueprints and price estimates, iron girders and concrete frames, managing the county’s next construction project.

Slowly, the SHU filled up with men, boys, old-timers, and fresh new jacks—scared and pissed as hell. They slept their days into night. They tried to shout and scream their loneliness away. They abandoned their last meager vestiges of humanity to all that concrete, glass, steel, and technology. All while Officer Saner leafed through one more motorcycle magazine, or did one more word search, before flipping the intercom switch to listen to one more goddamn complaint—a complaint he had no intention of doing anything about.