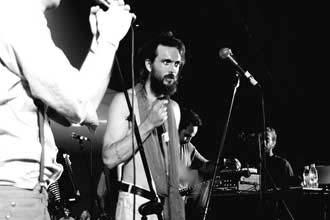

Photo: Wikimedia Commons

Flaming Lips frontman Wayne Coyne is almost as well known for his foul-mouthed frankness as he is for his group’s wild shows and hits like “Yoshimi Battles The Pink Robots.” The Flaming Lips are touring in support of their most recent album, Embryonic, and will release, later this week, their full-length take on Pink Floyd’s Dark Side of the Moon—on vinyl. We caught up with the witty, acid-tongued frontman to grill him about Floyd, plastic disks, and the sublime beauty of watching an asinine Radiohead fan get beat up at Lollapalooza.

Mother Jones: You recently covered Dark Side of the Moon, one of the best-known and best-selling albums of all time. What made you decide to tackle it?

Wayne Coyne: As your record’s getting ready to come out, you do these negotiations with a lot of different people who are going to be putting your stuff out. iTunes is one of the major outlets now, and they always want an exclusive thing. We’d done this double record (Embryronic), and they said “Wayne, do you have any extra songs that we could use as exclusive things?” Out of sheer not knowing what to say to them, I kind of said “Why don’t we do a version of Pink Floyd’s Dark Side of the Moon?” And then about a week later, they came back and said, “Hey, were you serious? We checked into it legally, and you could.”

Some of these songs are some of the most well-known songs ever. I don’t think you could play “Money” for very many people that love music and they wouldn’t know that song. So we took a couple of the songs we thought people would know the most, like “Money” and “Breathe,” and we thought, what could we do with this?

I think in the beginning, some of the arrangements seemed strange and funny and different. And then it set us on a path and we said, “Fuck it, let’s just see what we can do.” And it’s not that many songs. I think people forget it’s not like the Beatles’ White Album. It’s only 9 songs, and there are a couple instrumentals, and some of the songs are similar in tone. And knowing the record as well as I do, it didn’t seem like “Oh boy, what are we going to do?” A lot of the songs are just such perfect songs. You really can almost do anything you want and it will work.

MJ: Did you go in with a certain approach about how the songs should be changed?

WC: I don’t want to get too esoteric about it, but I always liked the idea that a punk-rock freaky group would do Dark Side of the Moon, which is about death and self-rebirth. And even though it seems like it’s about space rock, it really is about this inner space—what’s going on inside your mind, and discovering empathy, and what is death and time, and what do they mean within the context of your own sad existence. So when we had our chance, I thought, let’s put this primitive punk-rock spin on it. I don’t know if all of it seems punk rock or primitive. But for some of it, there’s definitely a different sort of mood to the songs.

MJ: You collaborated on this with your nephew’s band, Stardeath and White Dwarfs. What was it like working with them, and what did each group bring to the table?

WC: My nephew’s group already plays a lot of songs with us. Of course, I’ve known Dennis [the singer] his whole life, and we’ve played a lot of music together, and he helped me make my movie Christmas on Mars. So we’re always around each other anyway. So when we decided we were going to do it, I just automatically said, “Who don’t you guys take these songs, and we’ll try these songs and we’ll just get to task.” I don’t think any of us thought this would be the greatest thing ever. It’s all very stressful and you don’t know—are you ruining these great songs? Not just for the audience, but are you ruining them even for yourself? Once you dissect them and figure out how they really work, you’ve kind of stifled the magic. But I think we discovered you do stifle one type of magic, but it opens up another type of magic.

MJ: There’s something of a vinyl resurgence taking place right now. Why do you think that is—and why did you want to release the album on vinyl, too?

WC: We’re lucky that the people who put out the vinyl at Warner Bros really put as much care and as much love into these releases as probably has ever been done. We sometimes will have the music remastered three or four times to make sure it sounds great coming from those plastic discs. People don’t realize there’s a vast difference between the way it sounds on your computer, or on your iPod, or on your CD. All these formats take some form of—I guess expertise isn’t the word, but you have to be listening, saying, “Does it sound good now that it’s on this weird plastic?”

I think the more music becomes something you could simply download and have on your iPod, I think to a lot of people that is plenty, but to some people, they still want these artifacts that are touchable, and you can smell them, and look at them, and hold them and just have other dimensions of experience with this music. And I guess I’m one of those people. I like stuff and I like making stuff and obviously there’s an audience that likes it as well.

MJ: I want to ask you about your live performances, which are known for being crazy—confetti, balloons, the bubble you come out into the audience in. What made you decide to do such out-there shows?

WC: I don’t think it was designed to be this thing. We recorded this record called The Soft Bulletin in 1999. I made in my mid-30s, and it’s about death and it’s about finding yourself in a different dimension in your life—all these serious and suicidal states of mind. Not in a desperate way, but trying to see the beauty of life through the eyes of death. And I knew when we were making this record, we wanted to make this powerful music. But I also knew we were going to be playing Saturday night somewhere to a bunch of people who were 22 years old and wanted to take LSD. And I thought, I don’t really want to stand up there as this older guy and say, “You are going to die. And even if you are partying tonight and want to have sex with your girlfriend, you’re going to die, motherfucker.”

So I said if we’re going to perform this music, instead of it seeming like some existential gray moment, why don’t we make it seem like it’s a fucking crazy birthday party? So in a sense I’m singing about death but it looks like a birthday party. And I didn’t really think that it would be the best thing ever or anything. But I thought this would let me stand up there and sing these songs as best I could, and let the audience go home and love the moment. And they could look at me as a guy that’s just singing songs, instead of a guy that’s telling them some other form of a truth that they don’t need to know yet. So with that, I thought, I’ll pour blood on my head, and I’ll have balloons, and we’ll do confetti. And we just kept doing that. So instead of the shows getting smaller every time, we would just make it more of a celebration. We thought, well, if we did two boxes of confetti last night, why don’t we do five tonight and see what happens?

MJ: Any groups in particular that you like to see live, and are inspired by?

WC: There would be tons. I know it sounds cliché: Not this summer but the previous summer, I saw Radiohead at Lollapalooza, and that would be a show I bet a million people would say was a great show. But for me, I was standing up on the platform above them because I was lucky enough to be invited onto the stage to watch them. And they were playing my favorite song of theirs, while half a mile away in Chicago there was a fireworks display happening after a baseball game at the same time. So you have to imagine, I’m watching Radiohead, and then I can look over and see this fireworks display. And then at the same time—and here’s where I get to have experiences not everybody would have—there was this asshole that kept trying to bumrush the stage getting beat up by the security guards. I know that sounds horrible, but he deserved it. Radiohead’s playing, fireworks, the asshole is getting what he deserves—great moment.

MJ: One last question: Have you listened to your version of Dark Side of the Moon while watching The Wizard of Oz?

WC: I believe it probably has to do with how stoned you are as to how well you think that [connection] works. For me, I’m glad people like to get stoned, but I don’t really like to get stoned. So for me it never really worked that well because Dark Side of the Moon ends and there’s still 45 minutes to The Wizard of Oz.

I would say anybody who’s willing to listen to Dark Side of the Moon and watch The Wizard of Oz is already a very sensitive, creative person. If you’re willing to do that, you’re going to see possibilities in things. So it does actually work. But I think anything probably would. The movie people are saying our version of Dark Side of the Moon works for is Tron. I don’t think Tron is probably a very good movie, but whoever smoked the right amount of pot and put those two things on at the same time, I’ll let them be the judge.

Click here for more Music Monday features from Mother Jones.