Cairo, Illinois—At New Madrid, in Missouri’s bootheel, I stopped to ask an elderly man a question about the earthquakes, and, after hearing about how the river flowed backwards*, mentioned my next stop upstream. He told me I should go right on past it: “I’m old. I’m 75. My grandmother used to go to Cairo to go shopping. There’s nothing to see there.”

Cairo, Illinois—At New Madrid, in Missouri’s bootheel, I stopped to ask an elderly man a question about the earthquakes, and, after hearing about how the river flowed backwards*, mentioned my next stop upstream. He told me I should go right on past it: “I’m old. I’m 75. My grandmother used to go to Cairo to go shopping. There’s nothing to see there.”

When I asked him why, he paused, leaned kind of close, and dropped his voice: “Well what I’ve heard, it was blacks. You know what I’m saying, ok?”

Ok.

“Don’t get me wrong, there are good blacks. But I think you know what I’m saying.”

I guess I do. Not that I think blacks killed Cairo, but in the sense that human shortcomings of some sort (as opposed to, say, plate tectonics) did the job. Since the early planning stages of the trip, we’d circled Cairo on the map, mostly because that’s where Huck and Jim missed the turnoff on their way downriver, but also more generally, because it’s a river town’s river town, with a historic and geographical significance that dwarfs its actual size. Or it was. Today, Cairo’s mostly a ghost town; the population’s shrunk from 15,000 to 3,000, an exodus brought about first by economic downturns and the denouement of river life, and then by some of the worst racial conflict anywhere in America.

What you see today makes you double-check your Rand McNally atlas to make sure you’re looking at the right place. The old downtown consists of a half-mile-long stretch of late 19th- and early 20th-century commercial buildings, only one of which (admittedly a rough count) seems currently occupied. Since it’s more expensive in Cairo to knock down a building than it is to just let it rot, most of the buildings are boarded-up; the rest have simply been abandoned in such a state that the nearby vacant lots, some with still-visible tile floors, seem gentrified by comparison. No doors, no windows, no signs, no people. You half-expect to find Wall-E roving around the ruins searching for AA batteries.

Instead, a few streets over, you’ll find something even stranger: Ace of Cups, a coffee shop, bookstore, community center, and record label all in one. The big sign, scrawled in youthful purple-and-gold lettering in a town that generally hues rust-brown and weathered, may as well be written in cuneiform. Ace is the only standing structure on its block, and at the time of its opening, the first new business to come to town since Denny Hastert was still Speaker.

One of the not-so-heady discoveries I’ve made on this trip is that it can sometimes be darn near impossible to find a cup of coffee and some Wi-Fi. At the Cumberland Gap, a woman at a dry-cleaner told us the only place that might be open would be a Starbucks—45 minutes away. Then she laughed. So it was surprising enough to find a coffee shop in Cairo.

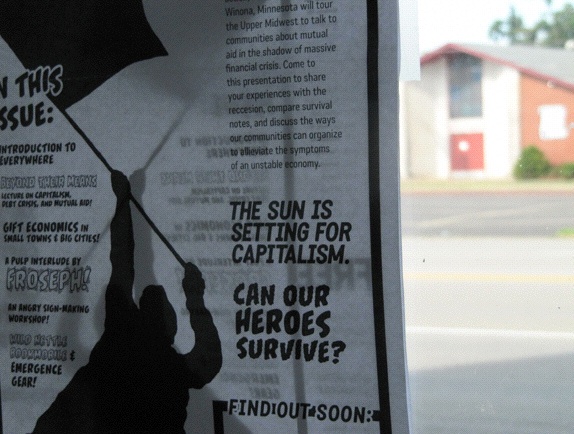

(Photo: Alex Gontar)But Ace of Cups is not just a coffee shop. Like I said, it’s a not-for-profit coffee shop/community center/used bookstore/record label/thrift store—and it’s run by, if not outright anarchists, at least anarchist sympathizers. There’s anti-meat literature and a post warning of the death of capitalism taped to the window, and in a cassette we picked up for $4, Chris Johnston and Adrienne Toole, two of the three co-founders, sing about starting “an anarchist bookstore” in the middle of nowhere.

(Photo: Alex Gontar)But Ace of Cups is not just a coffee shop. Like I said, it’s a not-for-profit coffee shop/community center/used bookstore/record label/thrift store—and it’s run by, if not outright anarchists, at least anarchist sympathizers. There’s anti-meat literature and a post warning of the death of capitalism taped to the window, and in a cassette we picked up for $4, Chris Johnston and Adrienne Toole, two of the three co-founders, sing about starting “an anarchist bookstore” in the middle of nowhere.

The guy who made my ice coffee lives in Southern California; he’s here on a summer internship. He loves Cairo so far—especially all the empty buildings. Zach Rappatoni, the third co-founder, moved from Orlando in search of small town without too much sprawl, some place where he could plant his flag and do something useful.

“It’s not like we came to Cairo to do this,” he explains. “We got to Cairo and decided to do this.”

If Ace of Cups were in San Francisco, it might raise a few eyebrows; in Cairo, it’s as if the Eagle just landed. The place is sprawling: There’s a side room, decorated with old maps, reserved for board games; there’s a door marked “Goblins,” which is actually just a storage closet, and a storage closet that’s packed with various old clothes and toys, all on sale for $1. You can buy CDs and t-shirts, and of course, books. You can play the piano, or paint something, or just sip your ice coffee and wonder what the heck is going on. Pretty much everything at Ace of Cups is for sale, and no one’s buying.

On a good day, Zach says they’ll bring in 10 or 12 customers, about half of whom are, like us, just passing through. They might make $27.

“There are the people asking why we’re here, and don’t really want us here, for whatever their reasons are,” he says. “The mayor’s never been here. It just seems like the mayor and the other powers that be are not only not for us, but also against us.”

Afterwards, I found out that the project was even more impermanent than Zach had made it out to be. As of July, Ace of Cups is for sale:

we have decided to pass the Ace Of Cups on to someone else who is hopefully better suited to keep it running. We are broke and homesick. I just posted more photos of the building and will answer any questions you have. We are not negotiable on the price unless you are 100% interested in keeping the community space open and running as is. You are more than welcome to buy it and turn it into anything you want as well.

I’m rooting for Cairo; it’s got too much behind its name to just fall off the map. Even in the early evening, Fort Defiance, situated at the confluence Huck and Jim passed in the night, was bustling with tourists from as far away as Shanghai, and barges stacked 10 rows deep. But it’s never a good sign for your city when even the anarchists are packing up and leaving.

*This can’t be emphasized enough. Four massive quakes in the winter of 1811–1812, each one bigger than the earthquake that hit Port-Au-Prince, rang church bells in Boston, and caused the Mississippi River to jump off its bed and temporarily flow backwards. A University of Illinois study released last spring reported that if just one such quake (let alone four) struck New Madrid today, it’d displace 7.2 million people and pretty much knock out Memphis.