Rosemary Pritzker

A decade ago, when I first met William Upski Wimsatt, he was a 27-year-old, shit-talking graffiti artist out promoting a book called Bomb the Suburbs. In it, he declared that hip-hop would liberate America from the suburban mentality—which was all about escaping from people of color, the poor, and having to deal with urban social ills. “I want to live in an America without ghettos and suburbs,” Wimsatt wrote. At a reading, I watched him jump around the stage, bouncing his Jew-fro and screaming at the 20 or so young people that made up his audience. I don’t remember what he said, but he made me feel like a giant capable of blowing up the system in order to end poverty and racism in America.

In subsequent years, Wimsatt tried to transform his verbal bombs into political actions, but he couldn’t find any meaningful channels for changing government policies. “To change history, you need to build organizations,” he declared in his sophomore effort, No More Prisons. Putting his money where his mouth was, Wimsatt went on to cofound dozens of political organizations, including The League of Young Voters (originally called The League of Pissed Off Voters) and Generational Alliance. This year, he’s been volunteering with TheBallot.org—a national database of progressive voter guides in each state, as well as the Coffee Party—a lefty grassroots counterpunch to the tea party movement.

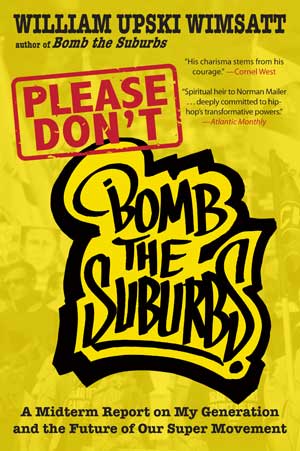

A month ago, Wimsatt called me to say he’d written a new book, Please Don’t Bomb the Suburbs. Say what? Was Wimsatt caving in? After Glenn Beck’s relentless attacks had led to the resignation of his friend Van Jones? I decided to get Wimsatt on the record about his book, which he calls “a blueprint for building a Super Movement 2020—a 10-year plan to build progressive power.”

Mother Jones: In Bomb the Suburbs, you ask people to take risks, call it out, and be real. So I’m confused as I read Don’t Bomb the Suburbs. Are you now saying young people need to worry more about building their resumes than speaking truth to power?

William Wimsatt: We totally still have to take risks, and probably bigger risks. But smarter risks. When I was younger, the risk was going out and doing graffiti and writing political messages and trying not to get arrested. Being the one who stands up at a meeting and pisses everyone off by laying it out on the table. Those are good risks, but this is not Daniel Ellsberg leaking the Pentagon Papers. First, he had to get a high-level job in the Pentagon. He probably had to spend decades with a lot of people he didn’t like very much, making compromises, and not having so much fun. So, it’s a balancing act.

MJ: But I don’t see massive numbers of people sacrificing their careers to take that kind of risk? Do you?

MJ: But I don’t see massive numbers of people sacrificing their careers to take that kind of risk? Do you?

WW: I see a lot of folks sacrificing and taking risks. The Trail of Dreams folks for instance—undocumented students from Miami who walked to DC. They went to a Klan rally in Georgia. They went to Arizona and hugged Sheriff Arpaio! They’re going around the country documenting stories of families broken apart by local 287(g) laws. That’s courageous because they could be deported at any time. We’re at a moment in history where brave action is needed on a mass scale.

MJ: So where should progressives position themselves in order to make a difference?

WW: Most of us grew up being told that power corrupts; you shouldn’t have power. You should become a teacher or writer or work in the nonprofit sector. In order to change the country, we need good people everywhere—business, real estate, law firms, and religious institutions. I think we’ve thought of what leads to social change way too narrowly.

MJ: So, election 2010: Which hopes or fears do you think will get young people to the polls?

WW: Issues are overrated. There are a million big issues. The biggest is simply knowing that we matter and our actions make a difference. There are millions of young people who voted for Obama, who will vote again, but they need to be told when the election day is, where their polling place is, what’s on the ballot, and why it matters. It’s that easy. That’s why we created TheBallot.org: to make it easy for people to create and share their own local progressive voter guides.

MJ: You just came back from the national Coffee Party gathering. How would you describe the momentum?

WW: The Coffee Party had a huge burst of energy this spring. We had 1,000 events in a month and CNN was covering our actions almost every day. We surpassed the tea party on Facebook: We now have more than 300,000 Facebook friends and a very active community that’s doing Coffee Vote. And we had over 100 Coffee With Congress meetings about financial reform and getting money out of politics. But there was no infrastructure or funding to sustain us. We were all volunteers. The national convention we just had in Louisville was pretty impressive. The media isn’t covering us every day, but we’re a lot more sustainable as an organization now. Post-election, the focus is on restoring democracy in the wake of Citizen’s United.

MJ: Is the left doing enough to fight climate change and provide pathways out of poverty?

WW: Hell no. I think future generations should get a lawyer and sue the shit out of us! But we did get Congress to pass the biggest green jobs bill in history and the biggest anti-poverty program in a generation as part of the stimulus. The stimulus needed to be way bigger. We needed to pass a climate and energy bill. But a movement is taking off, from community gardens to wind power surpassing coal as an employer. I see lots of people carrying eco water bottles and cloth bags to the grocery store. We’re taking great baby steps! We just need to keep our morale up.

MJ: Do you think Millennials have embraced racial justice and poverty issues?

WW: They’re trying! The Dream Act folks are impressive—undocumented kids doing direct action. ColorOfChange.org and Presente.org are the hottest thing out there. Platinum rapper Nas made a song about Fox News. Energy Action organized the biggest lobby day in history for green jobs. Student groups won an $80 billion victory to bypass bloodsucking loan companies and increase Pell grants. Is it enough? No way. But we have to celebrate every victory so we can build on it.

MJ: How do you plan to build this “super movement”?

WW: Step 1. Don’t get crushed in the midterms. A dozen volunteers could swing a House race. We need to jump in with both feet like we did in 2008, even though we’re not in the mood.

Step 2. We need to recognize we’re all on the same team. We’re all on this Titanic together. Even if we just take the most progressive 5 percent of the population, that’s 16 million people who are total kindred spirits. Most of them have names, phone numbers, and email addresses.

Step 3. After the election, November 13-14, people will be gathering across the country at Rootscamp sessions to talk about where we go from here. How can we build an integrated progressive movement as strong as the tea party? It’s an incredible time to make a case that we can’t lock up nonviolent, first-time offenders at a cost of $35,000-40,000 a year. It’s an incredible time to make the case that we can’t afford these 700 military bases around the world, and wars of discretion. It’s an incredible time to make the case that we need to invest in creating jobs. And somehow we’ve been losing the argument.

MJ: What’s the end game here?

WW: The most eloquent way I’ve heard it was, “Free people living in fair society and a healthy planet.”

MJ: Why didn’t youth organizing blow up after Obama mobilized hundreds of thousands of young people?

WW: Ha! Great question. First, a lot of lists and Facebook groups did grow: Rock the Vote, MoveOn, Organizing For America—their lists all got way bigger. One structural problem is that donors expect miracles from youth groups, like they’re magical ponies that run on pennies! This generation is the most progressive in recorded history. We voted for Dems by 22 points in 2006 and 34 points in 2008. Anyone who believes in progressive change but doesn’t invest in youth and leadership in communities of color is not to be taken seriously. Finally, it’s because we—and I include myself in this—are just not imaginative and inspiring enough. It’s game time. We have a huge opportunity!

Children of the ’80s: eighth grade graduation.MJ: You told me earlier that you’ve been thinking of race in a new way. How so?

Children of the ’80s: eighth grade graduation.MJ: You told me earlier that you’ve been thinking of race in a new way. How so?

WW: I think the realities of race have changed quite bit in the last 15 years. But my thinking about how to be a good “anti-racist” white ally has evolved dramatically. I learned the hard way that a lot of the orthodoxy on how to be a good white person is too much about hating yourself. And that doesn’t actually end up helping. Basically, we can’t love people of color if we don’t love ourselves. What we need is to love both.

MJ: How has this realization affected your work?

WW: The orthodoxy for good white men in the movement is to create space and get out of the way, so I was very focused on not dominating. What I actually needed to do was be a good manager. Being an executive director is extremely hard! It takes a lot of different skill sets and types of intelligence. It’s like being a mini-Barack Obama. It can be very isolating. No one understands except other executive directors, and you can’t talk to them because they’re your competition.

MJ: Does it still make sense to talk about hip-hop activism?

WW: The moral and political power of hip-hop has faded, but there is so much vibrancy in new and social media—people making YouTubes and doing green stuff. There are still millions of people who’ve grown up and been influenced by hip-hop and punk and rave and jam bands and who are socially and culturally and politically attuned. So, how do you awaken and organize that sleeping giant?

We have to be a little bit like Malcolm Gladwell in understanding and building social phenomenon. I always make fun of the philanthropic spectrum—they are just now figuring out about hip-hop, which had its best political moment 20 years ago. We have to be more on the ball with understanding popular culture and connecting it to movement culture. This rally that Stewart and Colbert are doing could be the most galvanizing thing for progressive folks. And we are sitting around, like, “Ha?” There are kids putting out YouTubes with five million views talking in a funny voice. We need to figure out how to do that and connect it to something real.