<a href="http://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:John_Mackey,_of_Whole_Foods_in_2009.jpg">Photo of John Mackey from Wikimedia Commons</a>

Last August, John Mackey, the founder and CEO of Whole Foods, sparked outrage in the liberal blogosphere and a customer boycott by publishing a full-throated critique of Obamacare on the op-ed page of the Wall Street Journal. He argued that the country should “move in the opposite direction—toward less government control and more individual empowerment,” and held up Whole Foods’ own health plan as an alternative: “Our plan’s costs are much lower than typical health insurance, while providing a very high degree of worker satisfaction.”

But it turns out that Mackey’s claims, which also fueled conservative opposition to the Democrats’ health-care bill, were misleading. In a memo that he sent to all employees last month, obtained by Mother Jones, Mackey concedes that Whole Foods is actually sinking under the weight of its health care expenses. In the past seven years, he writes, the cost of the company’s health care plan as a percentage of its sales has gone up 60 percent. This year’s tab is “equal to about 10% of the total Team Member compensation of $2 billion,” Mackey complains. “On average over the past three years we have spent more on health care costs than we have made in total net profits!”

Far from being a model of do-it-yourself health care reform, then, Whole Foods’ costly insurance plan illustrates why Mackey’s opposition to the Affordable Care Act was misguided. Like other major grocery store chains, Whole Foods is facing rampant inflation in health costs. (Unlike Whole Foods, however, Safeway supported key parts of the ACA.) Experts blame this on a lack of incentives for doctors to control costs and the 44 million uninsured Americans who burden the system. The health care bill passed in March is meant to address those problems, in part, by mandating that everyone purchase insurance, subsidizing coverage for the neediest, and creating exchanges in which individuals can pool their resources to purchase affordable coverage. A report by the Business Roundtable, an association of CEOs from large companies, estimates that the bill could lower health care costs by as much as $3,000 per employee by 2019.

Yet Mackey, an avowed libertarian, appears to see only one upside in the passage of health-care reform: The opportunity to use it as a scapegoat for Whole Foods’ increasing health costs. In the memo, he informs his employees that their insurance deductibles will be increasing to $2,000 for the company’s medical plan and $1,000 for its prescription plan, a spike that he blames entirely on the federal government: “This is very important for everyone to understand: 100% of the increases in deductibles and out-of-pocket maximums in 2011 compared to 2010 are due to new federal mandates and regulations.” (His emphasis.)

But Whole Foods CEO isn’t being honest with his employees about the real cause of the company’s escalating health costs. Most of the ACA’s key provisions don’t go into effect until 2014. Major parts of the bill that kick in sooner, such new rules governing “mini med” plans offered by fast food chains, wouldn’t directly affect Whole Foods. And even then, the bill allows companies to petition for temporary exemptions from the new rules. “It really strains credibility to say that all of Whole Foods’ cost increases are due to the Affordable Care Act,” says Karen Davenport, the director of health policy at the Center for American Progress. Last year, for example, the average price of an individual health insurance plan rose 5 percent—part of a continuing hike in medical costs that began more than a decade before the ACA was passed.

A spokeswoman for Whole Foods confirmed the Mackey memo’s authenticity but declined to answer any questions about the company’s health care plan.

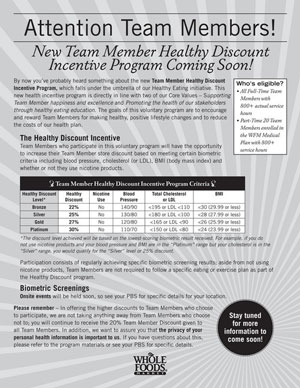

Whatever the reason for Whole Foods’ health care woes, its solution is simple: Cover fewer workers. Another internal Whole Foods document obtained by Mother Jones, “Guidelines for a Part-Time Work Force,” notes that part-time workers are less likely than full-timers to qualify for or sign up for the company’s health plan—a major reason why part-timers cost less. “Whole Foods currently has 17% of their team members as part-time,” the document notes. “The ideal situation is to have 30% part-time. By shifting the workforce by 13% we expect to substantially improve the company expenses by 2011.”

In short, Whole Foods’ solution is to become part of the problem Mackey is complaining about. By increasing the portion of its workforce that goes without insurance, it is burdening the health care system and driving up costs for everyone else. That’s exactly the type of vicious cycle that the ACA is intended to break. Starting in 2014, the law requires uninsured Americans, like Whole Foods part-timers, to purchase coverage through their employers or through nonprofit exchanges. If the exchanges work as envisioned, they’ll provide affordable care for the neediest while lowering insurance premiums across the board. Now that, as much as any organic, free-range Thanksgiving turkey, would be a reason to be thankful.