Gang of Four’s Jon King<a href=" https://vimeo.com/20565521">Carbie Warbie</a>

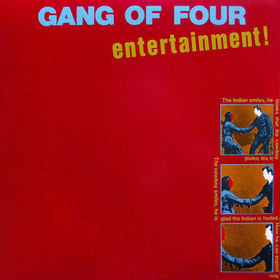

Circa 1979, on the recommendation of a nerdy record-store clerk, I bought a rust-colored LP called Entertainment!, the debut full-length from the British group Gang of Four. I was immediately intrigued. Led by the songwriting core of singer Jon King and guitarist Andy Gill, the foursome had created a sound that stood apart, even at a time of great experimentation in rock and roll. It sounded neither like the punk rock that preceded it, nor the synth-driven music emerging with bands like Devo, the B-52s, and dozens more.

Gang of Four’s songs were dark, stark, and spare, the lyrics deadpan, the beats martial yet funky, the guitar lines jagged as the obliteration of a beer bottle (as Kurt Vonnegut might put it) with a ball-peen hammer. King’s politics-infused-yet-metaphorical lyrics evoked images of a Western culture run amok. The band’s lone love song was an anti-love song, the distortion-laden “(Love Like) Anthrax.” Even the cynical album title was a perfect companion for youthful alienation. It rarely left my turntable.

I wasn’t the only one. Gang of Four has been name-checked as an influence for everyone from Michael Stipe to Kurt Cobain to the Red Hot Chili Peppers, whom Gill ultimately produced. They also became known for their explosive stage performances—the opener that blows away the headliner. The band’s popularity peaked with Songs of the Free, which was similarly agitprop but delved more into dance-music terrain; their taunting, funky hit, “I Love a Man in Uniform” was even banned by BBC Radio as British troops headed toward the Falklands. The group soldiered on through several full-length albums (Hard in 1983; Mall in 1991; and Shrinkwrapped in 1995), various lineup changes, and some lengthy hiatuses, before reuniting during the mid-aughts and touring with their original lineup.

Now, 16 years after Shrinkwrapped, Gill and King and their latest rhythm section (the reunion didn’t last) are back with fresh Content. This brand new record may not be as paradigm-shattering as Entertainment!, but it harks somewhat back to the band’s roots—it’s interesting and enjoyable and more than a little bit weird, which is something I’ve come to appreciate with these guys. I asked Andy Gill, now 55, about Gang of Four’s evolution, BBC censorship, and whether he’s managed to change the world.

Mother Jones: Entertainment! came at a time where rock and roll had stagnated and young bands were experimenting with all kinds of new sounds and ideas. Did you deliberately set out to flaut rock ‘n’ roll conventions?

Andy Gill: No, weirdly no. The thing was, me and Jon were both in love with a lot of different types of music, whether it was reggae or American black music, or the noise of the Velvet Underground or the Stones or Jimi Hendrix. There was a lot of stuff that we sincerely and in a really uncomplicated way completely loved, and I think initially the impetus for doing stuff yourself comes from your love of other music. I remember listening to a Muddy Waters record, I found it in a flat I moved into, an old copy of The Best of Muddy Waters—it was all scratched and stuff but I remember listening to it all the time because I loved it. It completely moved me, but the words don’t kind of relate to me, really. I remember thinking that, and then that we need to find—I’m talking about 1975-76, when the Gang of Four was starting—a language of our own. I felt that about music and I felt that about the lyrics. It was a case of trying to find a language that could express what we were about, and the existing musical forms didn’t quite do it.

MJ: It’s a pretty high bar you set.

AG: There wasn’t really a consciously discussed mission statement. And I think sometimes it can be easy to invent those things in retrospect and pretend that it was all clear or that we knew what we were doing. You kind of figure out what you’re doing as you go along. To me, the holy grail was  making a completely unstoppable groove which also surprised you—where the beats weren’t quite in the right place, but it didn’t matter because it would still rock you. It was intentional to do things which made you see stuff in a new way.

making a completely unstoppable groove which also surprised you—where the beats weren’t quite in the right place, but it didn’t matter because it would still rock you. It was intentional to do things which made you see stuff in a new way.

MJ: I gather you had some run-ins with your label, and instances where people tried to censor or ban your songs.

AG: It wasn’t the label. We were signed to EMI, one of the biggest conglomerates in the world, and you would think that they would have something to say about what it was we did, but it was kind of written into our contract that they wouldn’t have anything to say about what we did. And it became clear that they weren’t interested. Basically, our relationship was: They would pay for us to go into the studio and record our songs and then hand them over to EMI, wave goodbye, go on tour. And now and then the A&R man would come down, buy us a few drinks, and we wouldn’t see him again for six months. That was the extent of the involvement—sort of the opposite of what people imagine. In my experience as a record producer, the people who most get involved are the people from independent labels who feel they have more to do with it; it’s their “baby” kind of thing.

But the BBC, on a couple of occasions, banned us. On one occasion we were due to play Top of the Pops, which was the biggest thing in Britain at that time. It’s finished now but it was this TV series that went on for decades and it was the most influential rock and pop music program. “At Home He’s a Tourist” has the phrase “the rubbers he hides in his top left pocket.” They said, “This is a family show and you can’t say ‘rubbers’ on this show.” This was 1979 or whatever, they had a certain way of doing things. And we said we’ll change it, but to a word which has the same meaning, which is “packets”—the “packets” he hides in his top left pocket. And then a minute before we were due to go live, they came back and said, change it to “rubbish.” And we said, “Why?” And they said, “Rubbish sounds like rubbers and it will conceal the fact that we’ve censored you.” And that was when we walked off the show.

And then we did the song, “I Love a Man in Uniform,” and the Falklands was about to kick off and the single was doing extremely well, charging up the charts in the UK. And on the night that the British troops were about to go into the Falklands, the BBC controllers sent a memo that went around all the BBC, saying, “Do not play this song. We’re expecting to have to report casualties tonight. This song will not be played from now on, period.”

MJ: That’s a badge of honor, in a way.

AG: I suppose so. [Laughs.]

MJ: A lot has been made of your sound being inspired by Dr. Feelgood, and the band’s political outlook being inspired by Marxism. What are some of your contemporary influences?

AG: The Marxist thing is slightly overplayed. Basically, Jon and I both were in the fine art department at Leeds University. It was an incredibly interesting, heady atmosphere, reading stuff like Althusser or Walter Benjamin or Gramsci, basically neo-Marxists. I think we took elements from that,  no doubt; it became some of the conversations we were having. And yeah, Dr. Feelgood was a big inspiration. One of the best live bands ever, without a shadow of a doubt. These days, the stuff I like, the stuff that’s most inspiring, is day to day things that you read, that people say, things that stop the conversation.

no doubt; it became some of the conversations we were having. And yeah, Dr. Feelgood was a big inspiration. One of the best live bands ever, without a shadow of a doubt. These days, the stuff I like, the stuff that’s most inspiring, is day to day things that you read, that people say, things that stop the conversation.

MJ: The name Content seems like the modern upgrade of Entertainment!, the same sense of cynicism. What was your intent?

AG: I think central to what we do is thinking about what’s our role, how does this idea of being a band and getting on the stage and playing stuff or getting in the studio, what’s the function here, and how does it work economically? And I think Entertainment! obviously is very much about that, and I think in many ways we were exploring at that time what’s entertainment and what’s ideology and how do those two things relate to each other? And you’re right, I think the way Content works is very similar. I find that we’re asking are the same kind of questions we were asking on Entertainment!, and we’re coming up with not dissimilar answers. But I don’t think Content is a rerun. We’re trying to really just get to the essence of what we were about. In the past, occasionally, we’ve made the mistake of fooling around with what we’re doing, and it was mostly my fault fooling around with production techniques and samples and synthesizers and computers and losing sight of what our essence was. I think with this record we were trying to redefine that.

MJ: What are some of the specific inspirations for these new songs? Like, say, “It was Never Gonna Turn Out Too Good,” the song with the robot voice?

AG: The vocoder voice, yeah. It’s quite bleak. It starts out semiautobiographical in that I was indeed born in Manchester, but that’s where it ends. And it’s kind of someone ruminating on how difficult life can be and the struggles involved. With that song, I tried a lot of ways of doing it, and the conclusion I came to was just to strip everything out and have an awful lot of silence in there, which made it more surprising and a bit more shocking. And the vocoder voice is good because it’s designed to put some distance between the listener and the emotional content. You can kind of picture someone in a bar who’s had a couple of drinks who’s just like, it’s all coming out. And he doesn’t really care if you’re listening or not.

MJ: Gang of Four has always had these very deadpan critiques of consumer culture, of militarism, of workers being treated like dispensable cogs. What doesn’t necessarily come through is how you guys fit into that culture. Do you rebel against it personally, or merely comment on it?

AG: I don’t think we rebel against that in our lives. I think we get on with living our lives like everybody else does. Where we’re at in music is trying to explain what’s going around us either directly or by analogy and trying to create a parallel, an analog, sometimes musical, sometimes dramatic, that might be truthful.

MJ: Sixteen years is a long time between albums. What have you and Jon been doing during this time?

AG: I’m a record producer and that’s what I’ve been doing for the last 25 years plus; that’s my day job. But as much as I hugely enjoy working with other artists, there’s something more special about working on your own material. The people I’ve worked with have for the most part been incredibly interesting and it’s great. But when you work on your own thing, it’s all decisions of your own, decisions me and Jon make.

MJ: Do you think your music has aged well?

AG: Yeah. And I’ve aged well as well, just in case you were asking! [Laughs.] In the beginning of at 2005, when we all got in the same room and started playing the songs, it was like, holy shit, these things feel like we wrote them yesterday.

MJ: Do you feel like your politics have become more nuanced?

AG: To a certain extent. When I look back on Entertainment!, there’s an amazing amount of subtlety in those songs; they’re multilayered and they refer to a number of things and they are pretty sophisticated, but there’s no doubt that when you go through a number of decades you have a certain amount of perspective.

MJ: So looking back at your 35 years of songwriting, has Gang of Four had any impact beyond simply being entertainment?

AG: Yes, I think so. Me and Jon feel quite gratified by peoples’ responses. I mean, so many people, in North America especially, say, “When it comes down to it, you changed the way I think.” And I’m grateful for that compliment. If you can in some sense help in presenting something in a previously unseen way, I think you can’t ask for more than that, really.

Gang of Four’s North American tour runs February 4 through Feb. 21. Tour dates available on the band’s MySpace page.

Click here for more Music Mondays.