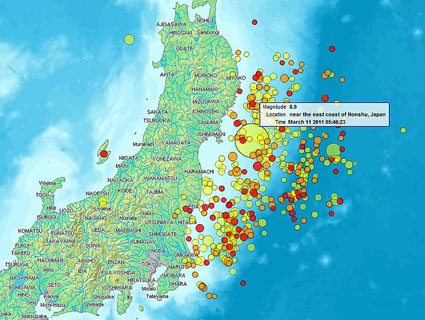

Map of the Sendai Earthquake 2011 and aftershocks.Credit: <a href="http://www.demis.nl/home/pages/home.htm">www2.demis.nl</a>

New Scientist notes that the seismic impact of Japan’s 11 March earthquake and tsunami advanced the flow of an enormous Antarctic glacier by about half a meter/1.6 feet. The observations were made by Jake Walter at UC Santa Cruz, and colleagues, who monitor the movements of the Whillans ice stream via a network of seismometers and continuously-operating GPS field stations on the glacier.

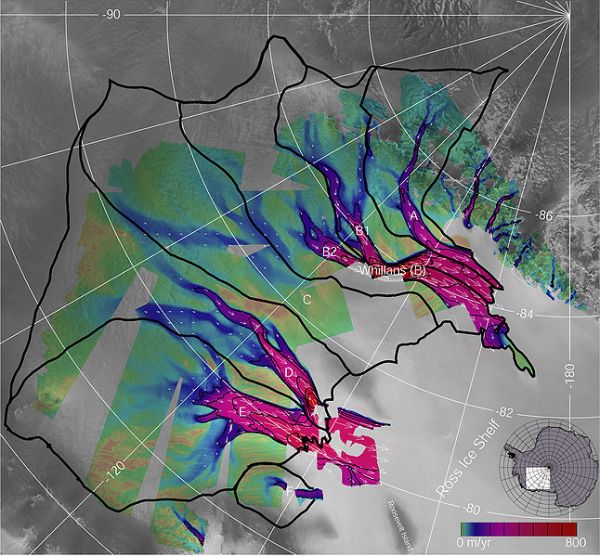

The Whillans is one of about a half-dozen large, fast-moving glaciers pouring from the West Antarctic Ice Sheet into the Ross Ice Shelf. A 2008 paper in Nature described the Whillans’ normal—albeit surprising—movement: advancing 0.5 meter/1.6 feet feet over a 10-minute interval, then holding still for 12 hours, then advancing another 0.5 meters. Each lurch, twice a day, sets off seismic waves equivalent to a magnitude 7 earthquake—big enough to register at seismographs in Australia, 6,400 kilometers/3,976 miles away.

Now Walter and team find that jolts from distant earthquakes can force a half-meter slip on top of the normal daily slips. These “stick-slip speed-ups” are sudden—of about 30-minutes duration, and fast—propagating at speeds of 100-300 meters-per-second/328-984 feet-per-second. They observed a similar slip in the Whillans after Chile’s 8.8 quake last year. Their findings appear in a new paper in the Journal of Geophysical Research.

West Antarctic ice streams are lettered A-E. Red: fast-moving ice streams. Blue: slower tributaries. Green: slow-moving stable areas. Black lines: watersheds. Credit: NASA, via Wikimedia Commons.

West Antarctic ice streams are lettered A-E. Red: fast-moving ice streams. Blue: slower tributaries. Green: slow-moving stable areas. Black lines: watersheds. Credit: NASA, via Wikimedia Commons.

Also in New Scientist, a discussion of the health effects of elevated radiation levels, noting that nuclear-core meltdowns create many radioactive elements, including iodine-131, two isotopes of cesium, and possibly strontium, tellurium, and rubidium.

Iodine is actively taken up by the thyroid gland to make hormones. If iodine-131, which emits beta particles, is taken up, this can damage DNA and cause thyroid cancer… Vast amounts of caesium-137 were distributed across 40 per cent of Europe’s surface after Chernobyl. Environmental levels remain elevated in wildlife, with restrictions still in place on eating some sheep farmed in the UK, and game and mushrooms from elsewhere.

Japan and its neighbors are monitoring air, food, and probably water just now to see which way the winds are blowing. Towards populated areas—Tokyo, the Koreas, China—would be horrible. The ocean seems a kinder alternative.

But what effects might radioactive elements have in the ocean?

Let’s look at what we know about mercury. I reported here in 2009 on a study in Global Biogeochemical Cycles showing how mercury from fossil-fuel-burning and waste-burning plants in Asia falls into the Pacific Ocean near the Asian coastline and is then carried by large ocean currents east towards North America. Along the way it’s ingested into the foodweb, eventually working its way up to tuna. Some 40 percent of Americans’ exposure to mercury comes from eating tuna hunted in the Pacific Ocean.

So, just as with European sheep, caribou, and mushrooms, the fish of the Pacific are at risk in the event of a full meltdown at any of Japan’s imperiled reactors. I would venture to guess that many more people depend on food from the Pacific Ocean than from sheep and mushrooms in Europe.

Tuna at Japanese fish market. Credit: User:Fisherman, via Wikimedia Commons.

Tuna at Japanese fish market. Credit: User:Fisherman, via Wikimedia Commons.

Finally, the amount of tsunami debris washed out to sea is enormous, and will likely travel ocean currents for some time, proving hazardous to shipping—far afield and far into the future.

On the plus side, these rafts of flotsam will also become highly-prized floating habitats for marine life to shelter under or within—particularly the larval life forms of so many fish and invertebrates. The ocean loves a reef, even a moveable reef.

Japanese tsunami debris on the open ocean, March 2011. Credit: US Navy, via Wikimedia Commons.

Japanese tsunami debris on the open ocean, March 2011. Credit: US Navy, via Wikimedia Commons.

The papers:

- Jacob I. Walter, et al. Transient slip events from near-field seismic and geodetic data on a glacier fault, Whillans Ice Plain, West Antarctica. 2011. J. Geophys. Res. DOI:10.1029/2010JF00175

- Douglas A. Wiens, et al. Simultaneous teleseismic and geodetic observations of the stick–slip motion of an Antarctic ice stream. 2008. Nature. DOI: 10.1038/nature06990

- Elsie M. Sunderland, et al. Mercury sources, distribution, and bioavailability in the North Pacific Ocean: Insights from data and models. 2009. Global Biog. Cycles. DOI:10.1029/2008GB003425