Zuma/Quad-City Times

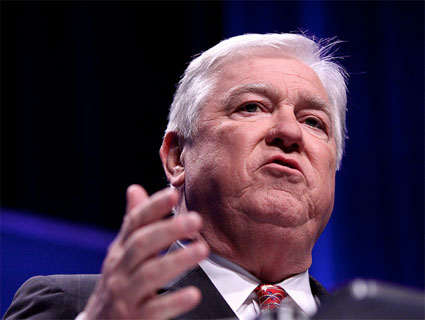

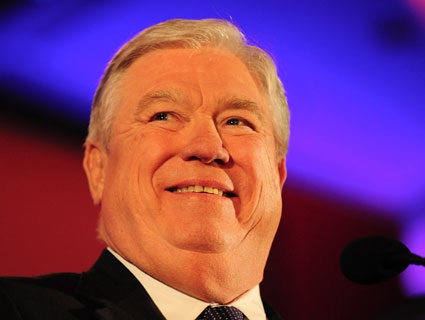

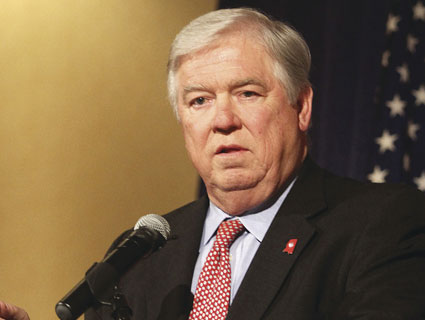

In 2004, Mississippi’s newly elected governor, Haley Barbour, and a pair of top state officials were sued (PDF) by children’s rights groups on behalf of nearly 3,000 wards of the state. Mississippi was annually fielding more than 10,000 reports of abuse and neglect at the time. The child-welfare system was so broken, advocates said, that it all but ceased to exist. Barbour and the appointees overseeing the child-welfare system, the suit alleged, “knowingly allowed [Mississippi’s] system to collapse, leaving Mississippi’s most vulnerable children defenseless.”

After a three-year legal battle, the state settled (PDF) the case (named after one such neglected child), Olivia Y. v. Barbour, agreeing to a sweeping set of reforms to Mississippi’s child-welfare system. Advocates hailed the decision as a major turning point for the state’s abused and neglected children. But here’s the problem: The Division of Family and Children’s Services, an executive agency controlled by the governor, has largely failed to keep its end of the bargain, raising questions about the leadership of Barbour, a jet-setting, high-profile Republican who’s weighing a presidential run in 2012.

Now, the attorneys who sued Mississippi in 2004 want a federal court to hold Barbour and DFCS in contempt (PDF) for shirking their responsibility to abide by the settlement. “They’re failing across the board,” says Shirim Nothenberg, a staff attorney at the New York-based advocacy group Children’s Rights who works on the case. “How can you expect him to manage the federal government if he can’t manage a welfare agency for kids?”

Laura Hipp, a spokeswoman for Barbour, said in a statement, “Gov. Barbour agreed to settle the Olivia Y. lawsuit, which addressed issues in the state’s foster care system that had occurred under his predecessors. The state is working to meet the requirements of the complex settlement.” A spokeswoman for DFCS did not respond to a request for comment.

Since the early 1990s, children’s rights groups had been warning of Mississippi’s broken system. Social workers were overwhelmed, handling an average of 48 cases per worker, a workload the state itself described internally as “BEYOND DANGER!” Health care for neglected children failed to meet demand; substantiated abuse and neglect rates in DFCS’ foster system were five times higher in 2005 than the federal government allowed; and most reports of abuse and neglect simply went uninvestigated by the state.

None of this was news to the Mississippi government’s top brass. Then-DFCS Director Sue Perry wrote in a 2001 memo that “the crisis needs to be addressed by whomever has the power to rectify the situation—before a tragedy occurs.” Then-Mississippi Attorney General Mike Moore told reporters in 2002 that one of his biggest fears was “that some child is going to die and they’re going to die on the state’s watch.” Even Barbour himself has said the state’s Department of Human Services, which oversees child welfare, “has collapsed for lack of management and a lack of leadership.”

The reform plan Barbour agreed to in 2007 amounts to a wholesale rebuilding of Mississippi’s child-welfare system. Limits were set on caseloads, and social workers now had to meet strict qualification guidelines to work for DFCS. Previously the state didn’t train DFCS employees in child welfare; now it had to operate a training unit to make sure employees knew what they were doing. The terms of the settlement also called for improved foster care conditions, a more streamlined path to adoption or reunification with biological parents, and beefing up child safety measures within the system to curb abuse and neglect. Nearly every corner of the Mississippi’s system was set for an overhaul.

Except, four years later, that overhaul hasn’t happened. According to the independent monitor assigned by the court to the Olivia Y. case, DFCS, under Barbour’s watch, has struggled to implement the required reforms. A 2010 report (PDF) by the monitor, Grace Lopes, noted that DFCS had missed deadlines laid out in the settlement, and was nowhere near on track to meet the requirements agreed to by the state. While child welfare funding had increased and a new management team was in place, the state was still failing badly. In some instances, Lopes wrote, there was “no evidence” that Barbour and state officials had even tried to comply with the settlement.

In October, the attorneys who had sued Barbour years earlier filed a contempt motion. Of the 119 requirements Mississippi needed to meet by the end of 2009, it had partially or fully fulfilled only 17, according to legal filings. Barbour’s administration failed outright to meet 52 of the requirements, and neglected to provide data to Lopes on the remaining 50, so she couldn’t assess whether the state had done what it had promised or not. The lawyers say extreme measures are now necessary to fix Mississippi’s child welfare system, including appointing a receiver who would seize control of DFCS and force changes to be made. “Mississippi’s court-ordered reform of its foster care system is moribund and children continue to live in jeopardy,” the motion concludes.

Nothenberg, the attorney with Children’s Rights, ultimately blames Barbour for the continued failure of Mississippi’s abysmal child-welfare system. “It’s the governor’s agency, and nothing is happening,” she says. “Barbour needs to be paying attention. This is his state, and these are his kids.”