As the story goes, the folklorist Alan Lomax was traveling around Mississippi with his recording equipment in the summer of 1941 when he came upon the house of a blues singer named McKinley Morganfield. Lomax recorded a few tracks for the Library of Congress and moved on, later mailing Morganfield a check for $20 and two copies of the record. What Lomax couldn’t have known at the time was that Morganfield, better known today as Muddy Waters, was to become one of the most famous blues singers of all time—the undisputed king of the electric Chicago sound.

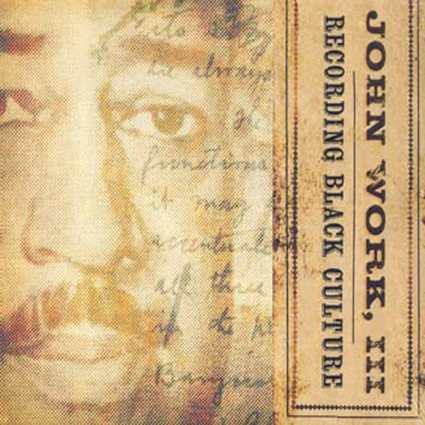

Morganfield, along with Son House, went on to be known as one of Lomax’s greatest discoveries. And while it may be true that without Lomax, we might never have heard of these artists, it’s worth remembering that—despite what his own memoirs suggest—Lomax didn’t actually discover either of them. That credit falls to a little-known black folklorist named John Work III, who died 44 years ago this month.

The long history of famous men is haunted by forgotten heroes. There are those like Alfred Russel Wallace, the biologist who proposed the theory of evolution before Darwin did. Today, if he is remembered at all, it is not so much as the man who first conceived of evolution by natural selection, but as the man whom history forgot to credit—a historical nuance not fit for high school biology texts. In Wallace’s case, Darwin attempted to give him credit, but history was intent on forgetting him. Work’s absence from the historical record is more suspect: Lomax devoted only one sentence to him in his own writings.

John Work III, born in 1901 in Tullahoma Tennessee, was a folklorist at Fisk University for almost 40 years. He attended Julliard and held music degrees from Yale and Columbia. According to music writer Dave Marsh, Work was Lomax’s partner and guide in the early 1940s. He led Lomax first to Son House and later to Muddy Waters, where Lomax recorded part of what would later be released as Down on Stovall’s Plantation. “Lomax never credited Work, but recent research has established him as at least Lomax’s equal in the study,” Marsh writes.

The omission of Work from the history of folklorists who traveled the south has had a significant impact on the way we understand delta blues music. The fact that Lomax and his father were white has led many to contend that the mythology of the blues was created by white record collectors. This is essentially the argument of Marybeth Hamilton in her 2008 book, In Search of the Blues. In a review of Hamilton’s book, Marsh sums her argument up this way:

[S]he describes the blues as an idea that developed as the result of a search for a pure aesthetic expressed by primitive African-Americans untainted by the modern world. The seekers, some in the service of white supremacy, some operating under the banner of Popular Front proletarianism, some in the thrall of art for arts sake, hoped to locate the one true voice of the Negro in the deepest, darkest South.

Consider that Work was the one who found Son House and Muddy Waters and this theory begins to fall apart. As the later chair of Fisk’s music department and a member of the American Society of Composers, Authors and Publishers, it’s unlikely this black folklorist was chasing some sort of “primitive” sound or, for that matter, working in the service of white supremacy.

Though almost certainly wrong, Hamilton’s theory—and the acceptance that it has received—betrays our discomfort that a white ethnomusicologist has somehow taken center stage in a narrative about black musicians. Lomax wasn’t a fraud; he spent his life recording folk songs across the American south, the Caribbean, England, Scotland and elsewhere. But in putting himself at the center of the history he was trying to tell, he necessarily muddied it. Neither Lomax nor Work deserve credit for the songs they recorded. As Marsh puts it, “sometime soon, we need to figure out why it is that, when it comes to cultures like those of Mississippi black people, we celebrate the milkman more than the milk.”

Click here for more music features from Mother Jones.