A destroyed house in Joplin, Mo.Andy Kroll

A demolished house in Joplin, Mo. Photographs by Andy Kroll

A demolished house in Joplin, Mo. Photographs by Andy Kroll

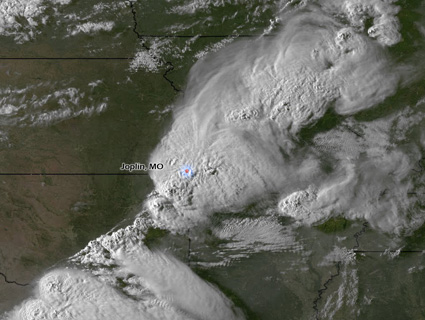

Driving into Joplin, Missouri, from the north, you wouldn’t know the most wicked tornado to strike this country in six decades had swept through this small town. Turning onto Main Street and heading south, a familiar tableau of small-town America rolls by—mom-and-pop diner, barber shop, hardware store, and plenty of vacant storefronts—all of it untouched. But before long the scene changes abruptly to one of panoramic destruction, an unrecognizable confetti of splintered wood, steel, glass, and rubble.

It’s been less than a month since a category F-5 tornado, the most powerful there is, cut a violent path through Joplin, population 49,000, ripping the roofs off houses and the houses from their foundations. It crushed the local high school. It stripped the trees of their branches and bark. It hurled cars and boats high and far. It killed 151 people.

I follow a procession of dump trucks headed east of Main Street into what is left of a modest, leafy neighborhood. There, a handful of houses still stand, windows ripped out, roofs shredded, lawns filled with the detritus of disaster. Walking the neighborhood, I find a Bible, a pencil sketch of Frodo and Sam from the Lord of the Rings, a stuffed horse, old VHS tapes. Relief workers have marked most houses with a spray-painted red X—condemned. A bulldozer will raze them within days. Some houses bear the names of the people who lived there, with spray-painted messages: “All OK” or “safe.” A few others show tallies of the dead. In some cases, there’s no house to speak of, just cement slabs where it once rested.

The wreckage stretches as far as the eye can see. “I’d say it goes ’bout two, two-and-a-half miles to the east, and maybe seven or eight to the west,” David, a government disaster-relief expert dispatched by the Army Corps of Engineers, tells me. He’s leading a crew of the clean-up workers who have descended on Joplin from far-flung states including California, Vermont, and Colorado. Using skip loaders and dump trucks and scrap grabs they are clearing the “right-of-way,” a 10-foot space between the street and the property. This lets residents access what’s left of their homes and salvage what they can before the bulldozers come.

Looking eastward at the tornado’s path.

Looking eastward at the tornado’s path.

About 7,000 properties were damaged in Joplin, David says, and a “majority” will be demolished. He told me he’d previously worked in Iraq, Afghanistan, and post-Katrina New Orleans. I ask how Joplin ranks. “I’d say number two,” David says. “Katrina’s number one, because it was a hurricane and a flood, and because so many people died. Thousands of ’em. But this is horrific…It’s like a war zone out here. Like a war zone.”

A half-mile away, a woman who looks to be in her sixties, with sandy hair, deeply tanned skin, and a mild southern accent, takes photos of a ruined house. It was her rental property, she tells me. She needs to get photos for the insurance company before the bulldozers arrive—tomorrow. She’s sad about the place, she says, but feels grateful to be alive. The death toll could’ve been much worse, she adds—like if Joplin High’s graduation, on the day of the storm, had been held at the high school itself, instead of Missouri Southern College. “Can you imagine that?” she asks. “I sure can’t.”

The city’s primary medical center, Saint John’s, suffered the same fate as now-crumbling Joplin High. The force of the twister shattered its windows, spraying patients with shards of flying glass and sucking people out the windows of the first-floor emergency room, the New York Times reported. Now the medical center stands empty and abandoned. A large American flag hangs on the east side of the building. Nearby, a nursing home has been wiped off the map.

North of Saint John’s, residents comb through the wreckage, sifting through mountains of plywood and siding. The tornado ripped the street signs from the earth, so people have put street names on tiny yard signs or spray-painted them onto the asphalt. Some streets aren’t marked at all.

Residents spray-painted their homes with news of the living and deceased.

Residents spray-painted their homes with news of the living and deceased.

The tornado, three-quarters of a mile wide, cut an unnervingly precise path. On some streets, houses at one end of the block are untouched while houses on the opposite end have been leveled. In some cases, the difference between destruction and safety is mere yards.

On South Bird Avenue, I meet Charles and Joyce Testerman, both in their 60s, who are sitting out on their front porch. Other than some damage to the roof and to a garage out back, the Testermans’ well-kept one-story home was spared.

Charles says he was at church when the tornado hit, but Joyce was at home. It was her sister who called Charles frantically to warn that the twister was headed their way. By that point Joyce, a small, fine-featured woman with wavy silver hair, had taken cover inside. All she could think to do, she says, was pray. “I just kept yelling, ‘Jesus, you are my fortress. You are my refuge. Pick that storm up and carry it away from me!'”

Charles listens, nodding. “I do believe that storm did rise up. Just like she said.”

The neighbors weren’t so lucky. Charles points to a house across the street. It looks undamaged, but Charles says the tornado lifted it off its foundation and set it back down again. When that happens, he explains, the insurance company usually declares it unsafe and tells the residents to move out.

But the Testermans really wanted tell me about the angels. “Angels just everywhere,” Joyce says with a sweep of her arm. “It was awesome.” Those angels, Charles adds, arrived from Texas, Washington State, Oklahoma, and other places—volunteers descending on Joplin to rebuild. “The entire street was filled with ’em,” he says.

Charles remembers a group of wisecracking Texans with a knack for cutting wood. They’d shown up with a massive 42-inch chainsaw and an even bigger two-man saw, offering to cut up a felled tree in the Testermans’ backyard for free. “Those fellas would cut some, then they’d stop and the funny guy would tell ’em a joke. Then they’d cut some more,” Charles recalls. “Didn’t leave till they finished. That tree must’ve been 140 years old.” The stump still sits in the Testermans’ backyard, eight feet tall—bigger than a Ford truck.

By this time it is late evening. I wish Charles and Joyce all the best. “It makes ya think that something this country lost, something great, well maybe it’s not lost after all,” Charles reflects. “People still help people.”