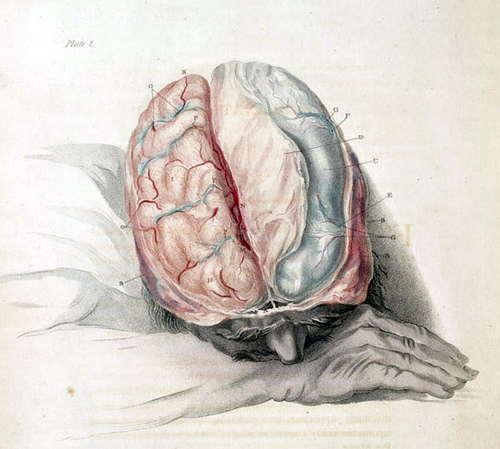

Brain_Blogger/<a href="http://www.flickr.com/photos/brainblogger/3138247450/sizes/m/in/photostream/">Flickr</a>

In a study trial lawyers are sure to find of interest, Israeli scientist Micah Edelson has found that people’s recollections of recent events can be altered by peer pressure. The study (published in Science this week) asked participants to view a movie in small groups. Directly after the movie, participants were questioned individually about it. Some participants were very sure their answers to interviewers’ questions about the movie were correct.

Four days later, the interviewers asked participants about the movie again (especially on the items the participant felt strongly they had answered correctly). However, this time, the interviewers presented the participants with false information about the film, allegedly provided by the other people in the participant’s viewing group. Edelson found that in nearly 70% of cases, the participant changed his or her correct memory about the movie to match the group’s incorrect memory. And in nearly half of these cases, the participant’s memory switch was long-lasting, meaning they might no longer remember their own, individual, correct version of the movie: instead, it had been replaced with the group’s inaccurate memory.

There has been research before showing people’s willingness to change their stories (even if they knew they were true) under social pressure. What makes Edelson’s research unique is he used an MRI scanner while people were answering interviewer’s questions. Edelson found that participants’ hippocampi and amygdalas showed activity only when people changed their answers to match their viewing groups. If they changed their answer because a computer told them they were wrong, the hippocampus and amygdala didn’t light up. The hippocampus is linked with memory and the amygdala with emotion.

“Our memory is surprisingly susceptible to social influences,” Edelson said during a recent podcast. This can be a source of concern to some, he noted, since “studies have show that… [witnesses] often discuss crime details with each other before testifying, and this can definitely have an influence on court cases.” As Edelson’s recent paper shows, a crime witness who’s had his or her true recollection of an event altered by some one else’s faulty recollection may lose their initial memory of the event forever. It’s neurologically possible for a witness’s (or a juror’s) memory of an event to truly change under social pressure.

Makes you wonder what effect the hippocampus and amygdala have on people who continue to believe crazy things (cough! Obama’s a Muslim!) even in the face of conflicting facts. Maybe their communities have actually changed their memories of events and they actually remember a different reality than others. Or maybe it doesn’t so much matter what you believe, as long as you think someone else believes it too.