He looks delicious.<a href="http://www.flickr.com/photos/camil_t/71527798/sizes/z/in/photostream/">camil tulcan</a>/Flickr

To help solve the debt crisis, the best thing I can do is die. Maybe not right now, but certainly before I put too much strain on the public purse—and since I’m 74, that means pretty soon. If I should be lucky enough to contract a fatal disease, I can do the right thing by eschewing expensive medical care that might extend my life. If that doesn’t happen, and I enter a slow and costly decline, then in the interests of the greater good I should take the Hemingway solution.

That’s pretty much the message of David Brooks’ column in today’s New York Times. “This fiscal crisis is about many things,” he writes, “but one of them is our inability to face death—our willingness to spend our nation into bankruptcy to extend life for a few more sickly months.”

Here’s how Brooks comes by his position: To begin with, he says: “The fiscal crisis is driven largely by health care costs.” Never mind two futile wars and 10 years of tax relief for millionaires.

Furthermore, he argues, the reason for these soaring costs is that very old and very sick people insist on clinging on to their miserable lives, when they ought to be civic-minded enough to kick off. It’s not the insurance companies, which reap huge profits by serving as useless, greed-driven middlemen. It’s not the drug companies, which are making out like bandits with virtually no government regulation. It’s not the whole corrupt, overpriced system of medicine for profit, which delivers the 37th best health care in the world, according to the WHO, at more than twice the cost of the best (France). No. It’s all about us greedy geezers. We’re the ones who are placing an untenable burden on the younger, heartier citizenry, with our selfish desire to live a little longer.

Brooks cites the usual figures: “A large share of our health care spending is devoted to ill patients in the last phases of life,” he writes, and Alzheimer’s patients will soon cost us hundreds of billions. He continues: “Obviously, we are never going to cut off Alzheimer’s patients and leave them out on a hillside.” (Thanks, Dave.) “We are never coercively going to give up on the old and ailing.” Nonetheless, Brooks hopes than many “old and ailing” people will make the choice made by Dudley Clendinen, a man suffering from ALS, who wrote a moving essay in the Times about his decision to end his life before the disease takes its full course and renders him “a conscious but motionless, mute, withered, incontinent mummy of my former self.”

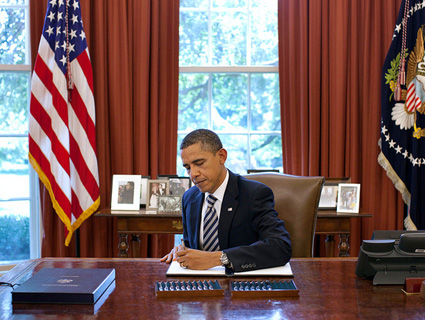

I have great respect for Clendinen’s decision. As I’ve written before in Mother Jones, I am a big supporter of what these days is called “choice in dying” or “death with dignity”—each person’s right to decide when and where and in what circumstances they will die. But I dont want anyone else making those decisions for me, or telling me when the time is right—not an insurance company or a Medicare bureaucrat, not Barack Obama or John Boehner, and certainly not David Brooks. I have every intention of being my own one-man death panel. But I won’t be persuaded to die a moment sooner than I want to just because it might save some money—money that could easily be saved by far more equitable and less draconian means.

Brooks writes that “it is hard to see us reducing health care inflation seriously unless people and their families are willing to and their families are willing to do what Clendinen is doing—confront death and their obligations to the living.” And why is this so hard to see? Because conservatives like Brooks don’t believe in challenging the profit-driven health care system, and the people who pass these days for liberals lack the moxie to stand up to them.

Based on models from countries like France and Canada, we could bring about whopping savings in health care expenditures through a single payer system without rationing or compromising the quality of care. Short of this, we could opt for much more regulation and still save more money than we could by pulling the plug on every geezer in the land.

If I have any obligation to the living, it’s to leave them with a better system than we have now—one that values all human life above profits. But I know that’s not likely to happen before my death—which, if I listen to Brooks, could be right around the corner.