<a href="http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ji_hZetz6fw">La Revista Magazine</a>/YouTube

This story first appeared on the New America Media website.

On a Sunday, in the Phoenix suburb of Surprise, state legislator Steve Montenegro stands behind the pulpit and preaches with confidence.

“Hermano, hermana, en su vida él no va dejar que se burlen de usted,” he says in Spanish before transitioning into English. “Brother, sister, in your life he won’t let anyone put you to shame.”

An audience of about 40 people, mostly Latino, listens to him attentively as he punctuates every sentence with a wide smile.

In his second term in the Arizona state Legislature, the 29-year-old immigrant from El Salvador is the only elected Latino Republican in the Arizona House, and politicos on both sides of the aisle view him as a rising Republican star. Montenegro, who is running for reelection in 2012, is the product of a national effort by Republicans to recruit and train more Hispanic candidates for office—including Florida Sen. Marco Rubio and New Mexico Gov. Susana Martinez—because they say Latino voters are shifting to the right.

Conservative Latinos praise him for immigrating legally, “the right way,” as others called him a vendido, or sell-out, for supporting legislation like SB 1070, which makes it a state crime for unauthorized immigrants to be in Arizona. (Federal courts have stayed key parts of the law, pending a final decision on its constitutionality.)

Montenegro said he never mixes politics with his role in the church and vice-versa. But his family’s church, the name of which he asked not to be mentioned in this article, has been an integral part of his life. He grew up looking up to his father, a Pentecostal pastor, speaking Spanish, and watching immigrant families like his struggle to make ends meet. “That’s where my values come from,” he says. “It’s who I am.”

This is precisely why he thinks he doesn’t need to try hard to understand the mindset of Latinos. In an interview at a local coffee shop, Montenegro says he gives voice to conservative Latinos with strong family values and prudent economic views who are tired of the hypocrisy of politicians from both parties. He says he is on a mission to fight stereotypes held by many, including some fellow Republicans. “(Latinos) would rather be in the sun on top of a roof in Arizona, 120 degrees, working hard, than showing up to the welfare office,” he said.

Montenegro, a brown-skinned man with short dark hair, has the demeanor of a meticulous businessman: calm, soft-spoken, and extremely measured when talking to reporters. He says he is satisfied with his current political career and doesn’t have his eye on a specific political post. Where his career goes “is going to be up to the voters and up to God,” he said.

“My calling is to serve. I’m a minister and I’m called to serve in that,” he said. “But I’m also…I believe with all my heart, that I’ve been called to serve the conservative, the cause of freedom.”

By “freedom,” he means less big government. And by “being free,” he means taking responsibility and working hard. “People love the fact that when I tell them, ‘I really stand against government oppression and big government,’ they believe me,” he said. “Because I was born in El Salvador, my parents have seen what a big oppressive government would do to you.”

Montenegro’s family arrived in Los Angeles when he was four years old. He is uncomfortable discussing his immigration history, which has long drawn the curiosity of many Phoenix Latinos. El Salvador was in the middle of a civil war when Montenegro and his family immigrated. His family did not seek political asylum or a church sponsorship, he said. Instead, he said, his father applied for legal residency through a family member who already lived in the United States.

At the time the family immigrated to the United States, Montenegro’s father was a pastor in the Iglesia Apostólica de El Salvador, a growing denomination of Pentecostals in Latin America. “My father said, ‘If it’s meant for us to be, if God wants us to go, we are going to get the paperwork,'” Montenegro said. “‘If not, we are not going. I’m not going to put my family through the heartache that it is to try to come to this country undocumented or illegally.'”

His family lived in Colorado, Michigan, and Canada throughout his childhood, until they settled in Arizona and his dad began preaching in a church in Surprise.

Montenegro remembers learning English in kindergarten, but Spanish was the main language spoken at home. That didn’t prevent his family from wanting him to assimilate with non-Latino cultures, he said. “Being an American to them, it wasn’t about segregating,” he said. “They didn’t embed in me, ‘You are brown, you have to be this way.’ No, they embedded, ‘You’re a child of God, you are a student, you have to be the best. El mejor hijo de Dios’ (the best son of God).”

Growing up, Montenegro took jobs to help the family. When he was 14, he worked for a few weeks helping with yard work with some people from the church but said he had to quit because he couldn’t take the extreme heat of Arizona. At another point he got a job as a busboy. He became an assistant youth pastor to his father. He spent five years as president of Arizona Messengers of Peace, a group within the Apostolic Assembly that provides counseling and guidance for youth.

But he had his heart set on becoming an attorney. He graduated from Arizona State University with a degree in political science and took an internship with Republican Rep. Trent Franks, thinking he could get a letter of recommendation from him to go to law school.

His eyes grow teary as he remembers his father’s advice when he was studying to take the LSAT. “Hijo, ocúpate de lo posible. Y déjale a Dios lo imposible. Él es especialista en lo imposible,” his father told him in Spanish. (“Son, take care of the possible. Leave the impossible to God. He specializes in the impossible.”)

He did well on the test, but politics found him before he started law school. He was recruited by a Republican political consultant during a luncheon in February 2008, where his boss Franks was a keynote speaker. The consultant, Constantin Querard, president of the political consulting company Discessio, LLC, says he immediately saw something in Montenegro. “I try to recruit more minority candidates in the Republican Party—it’s the right thing to do, particularly with Latino voters; their natural tendencies in so many issues line up so well with Republicans,” he said. “The problem is that we don’t have a very good messenger…and we have almost no one who can deliver the message in Spanish.”

Querard said that people like Montenegro help fight against negative and incorrect stereotypes about the GOP, especially when it comes to immigration issues. “Steve hopefully is the face of the future of the party,” Querard said, “and when other aspiring Latino candidates look at Steve, it will inspire them to recognize it’s very possible.”

Montenegro has risen quickly through the ranks in the state Legislature and is currently the speaker pro tempore. He is the candidate that Latino Republicans like Haydee Dawson were looking for. “His story is the epitome of the American dream,” said Dawson, a 33-year-old financial consultant in Mesa who also migrated from El Salvador when she was young. “He is part of a new generation of Republicans.”

Alice Lara, a spokesperson for the Arizona Latino Republican Association (ALRA) and host of the talk show Radio ALRA on KKNT 960 AM, agrees. She said Montenegro also offers Latino Democrats who are pro-life and conservative someone who aligns better with their values.

But not everyone is buying into the new, browner image of the Republican Party. “They’re using folks like Montenegro to try to give themselves a different image,” Democratic state Sen. Steve Gallardo said about the GOP. “Unfortunately, the vast majority of Latinos are going to look right through that disguise.”

Gallardo points out that Montenegro wouldn’t win in a district like his, where the majority of voters are Latino. He said it is mostly white conservative voters who have given Montenegro support. Latinos represent nearly one-third of Montenegro’s district. With a total population of 378,298, Montenegro’s is the largest district in the state, according to the 2010 Census. “I don’t care what his last name is; he is not representing Latinos,” Gallardo said.

Querard said people on the left wish politicians like Montenegro would go away because they destroy their argument that state immigration policies are driven by an anti-Latino sentiment. “They can’t fight that rising tide,” said Querard. “He is the first but there’ll be very many like him.”

Eye of the Storm

Before SB 1070, Montenegro supported a number of other controversial initiatives that put him in the eye of the storm. He was the sponsor of HB 2281 to ban ethnic studies classes, arguing that they promoted the overthrow of the American government. The bill, signed into law by Gov. Jan Brewer, is being used to try to dismantle a specific program in the Tucson Unified School District that focuses on Chicano studies.

Montenegro was also the major force behind a ballot initiative in Arizona to end affirmative action, which resulted in a decrease in funding for women’s education programs.

He said he gets frustrated with the argument that all Latinos’ views are monolithic or are pro-illegal immigration. “I think it’s wrong to attribute illegal immigration to the Latino community,” he said, “when the fact is that the majority of Latinos in this country and in this state are people that have followed the laws and are here legally.”

At his office at the State Capitol, he reads aloud an email in Spanish that was sent to him by a woman who identified herself as a legal immigrant in the border town of Nogales. She writes that she supports SB 1070 and goes on to say that she sees with sadness that the underage gang members in her son’s school are the children of “illegal immigrants.” A letter read by Republican Sen. Lori Klein on the Senate floor sparked controversy earlier this year by drawing a similar comparison.

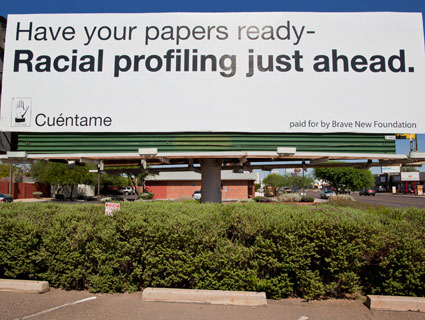

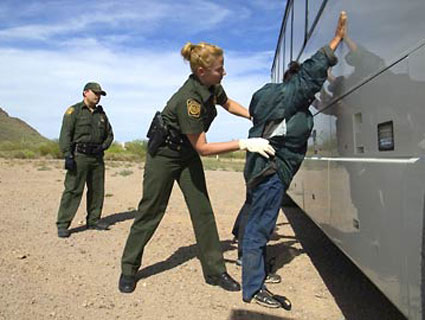

Montenegro’s perfect Spanish has made him a virtual spokesperson for SB 1070 on the Latino airwaves, fielding questions that it would lead to the use of racial profiling against dark-skinned people. “This is an issue that every country deals with,” he said. “For people to automatically say this is a racist issue, I feel that is wrong.”

Montenegro says SB 1070 has been widely misunderstood. It didn’t create a new immigration standard, but would have made police enforce the federal immigration laws already on the books by bringing uniformity to police enforcement, he said.

Several federal judges disagreed with Montenegro’s assertion by enjoining most key provisions of SB 1070, saying the state law intrudes into federal immigration enforcement. Still, Montenegro doesn’t think the immigration system is broken. “The process is there and there are millions of people that can attest to it working,” he said. “Can we make it better? Absolutely. Let’s do that. That’s out of my hands; that’s in Washington.”

He says he would be open to increasing the number of visas available for people to come to this country legally, and review the costs and expedite the process for those who have been waiting for many years to migrate. But he says he doesn’t support any form of amnesty. “This country has a big heart,” he said. “The problem is when the rest of the world wants to take advantage of that.”

Montenegro doesn’t see a solution in legislation like the DREAM Act, a bill currently in Congress that would create a path to legalization for young people who came into the country before the age of 16 and have enrolled in higher education or the military. He said enrolling in the military and giving their lives for the country is a noble cause, and no one would argue that someone should not get legal status because of that, but “you can’t equate that with other things like a student going to school.”

“I think it’s biased to be thinking of one group of people only, when 20 years from now you’re going to have the same problem,” he said.

He said Latinos should be outraged at Obama for not fulfilling his campaign promise of tackling immigration reform and then trying to blame the failure on Republicans. “Well, Mr. President, you have two years of all Democrats, both House and Senate. You promise something, you had the power to do it then,” he said. “I’m not advocating for what he promised, but I’m just holding his feet to the fire. And what did he do? Nothing.”

Montenegro says he wants it to be clear that as a politician he doesn’t speak for the church. No matter how much he has tried to keep the two separate, his connection to the church came under fire last year.

Carlos Galindo, a political commentator for the Christian station Radio KAZA 1290 AM, said he has gotten several calls from upset people who claimed they were undocumented members of his church and said they had helped pay for Montenegro’s education. “He says he doesn’t know if they’re undocumented or not, but he allows it because they’re flock and they go to his church—but he has a problem with them on the streets,” said Galindo. “There’s hypocrisy.”

Montenegro categorically denied those allegations, saying he got funding for his education through scholarships, loans, and help from his family. “At church we never ask people what their status is,” he said, adding that politics are not part of the conversation either.

An undocumented immigrant who claims to be a former member of the church spoke on condition of anonymity.

“It hurts me that he knows what are these people’s needs and he continues to try to oppress them,” said the source, who left the church a year and a half ago in protest of Montenegro’s political stance against undocumented immigrants. “He has forgotten that undocumented immigrants have family members that are not undocumented and can vote.”

Montenegro said when he took a stance in support of SB 1070, he didn’t do it as a minister or a pastor. “I did it as a legislator,” he said. “You can’t unite the two things. At church is not about politics. It’s about salvation.”

On this Sunday morning, he preaches about finding joy in the midst of oppression and finding strength through faith. On the church walls hang cardboard signs with the messages of the service: “Oppressed Go Free,” “Undo Heavy Burdens,” and “Break Every Yoke.”

“The reason why we are, the reason we live, is to serve him,” he says from the pulpit, as people burst into applause.