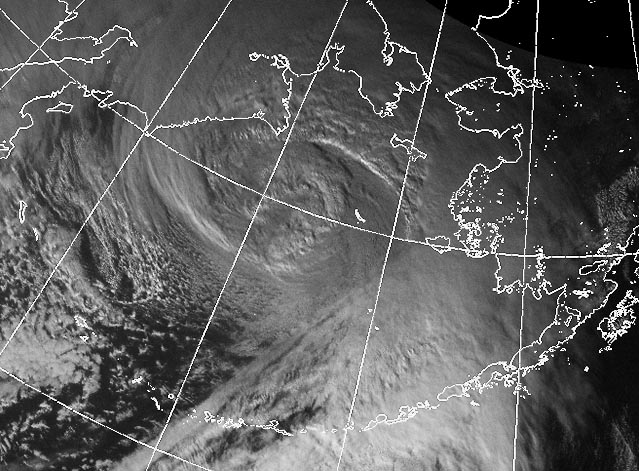

Bering Sea superstorm on 8 November 2011. : Credit: NWS, NOAAThe superstorm that howled out of the Bering Sea and slammed coastal Alaska yesterday didn’t get named, even though its lowest pressure of 945 millibars was as low as some Category 4 hurricanes. We haven’t yet begun to name high-latitude monsters—though that may change. Jeff Masters, in today’s WunderBlog, writes:

Bering Sea superstorm on 8 November 2011. : Credit: NWS, NOAAThe superstorm that howled out of the Bering Sea and slammed coastal Alaska yesterday didn’t get named, even though its lowest pressure of 945 millibars was as low as some Category 4 hurricanes. We haven’t yet begun to name high-latitude monsters—though that may change. Jeff Masters, in today’s WunderBlog, writes:

[M]ultiple studies have documented a significant increase in the number of intense extratropical cyclones with central pressures below 970 or 980 mb over the North Pacific and Arctic in recent decades. Computer climate models predict predict a future with fewer total winter storms, but a greater number of intense storms; up to twelve additional intense Northern Hemisphere cold-season extratropical storms per year are expected by the end of the century if we continue to follow our current path of emissions of greenhouse gases.

Shishmaref village, Alaska, inhabited for 400 years, battered by storm waves. Credit: NOAA.I wrote in An Arctic Sea Change, a 2007 MoJo photo essay by photographer Robert Knoth, how the Alaskan coastal village of Shishmaref was falling into the sea. Now we know the dynamics affecting Arctic coast villages are more complex than just rising sea levels. Dwindling sea ice allows for more evaporation from the ocean, which fuels larger Arctic storms and their accompanying monster storm surges. The battered land disappears even in advance of significant sea level rise.

Shishmaref village, Alaska, inhabited for 400 years, battered by storm waves. Credit: NOAA.I wrote in An Arctic Sea Change, a 2007 MoJo photo essay by photographer Robert Knoth, how the Alaskan coastal village of Shishmaref was falling into the sea. Now we know the dynamics affecting Arctic coast villages are more complex than just rising sea levels. Dwindling sea ice allows for more evaporation from the ocean, which fuels larger Arctic storms and their accompanying monster storm surges. The battered land disappears even in advance of significant sea level rise.

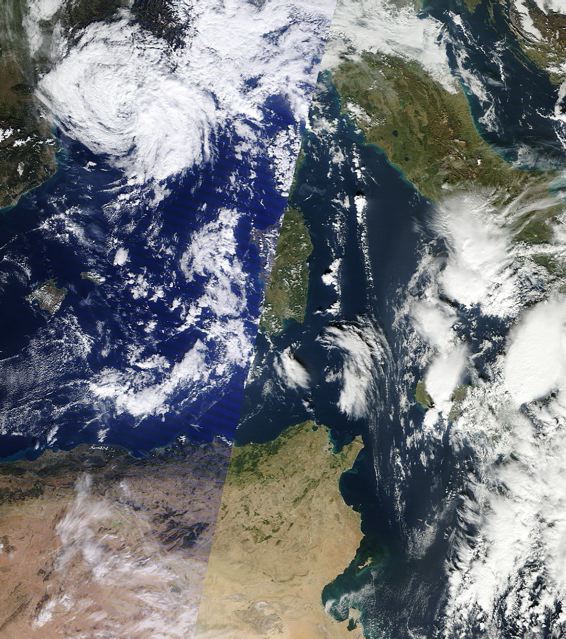

Hybrid tropical-extratropical storm Rolf in the Mediterranean Sea 9 Nov 2011. Credit: MODIS/NASA.

Hybrid tropical-extratropical storm Rolf in the Mediterranean Sea 9 Nov 2011. Credit: MODIS/NASA.

In another interesting weather development reported by Jeff Masters, a rare hybrid extratropical/tropical storm named Rolf developed in the Mediterranean Sea this week. Generally the waters of the Med are too cold for tropical storm development, though an occasional ‘Medicane’ forms. Rolf has delivered more than 15 inches/400 millimeters of rain to parts of France and wind gusts of 95 mph/153 kph. One study forecasts the Med will warm by 5.4°F/3°C by 2100—plenty warm enough for hurricane formation.