Sea otter nursing pup: Mike Baird via Wikimedia Commons.

A new paper in MEPS reports on the strong lingering effects of oil on sea otters in western Prince William Sound from the Exxon Valdez disaster that killed hundreds of thousands of birds and thousands of marine mammals 23 years ago.

The researchers report that exposure to oil has hardly ended—and the likelihood of exposure is highest for mothers with pups than any other members of the otter population.

Although initial assessments found the Exxon Valdez oil decayed quickly and therefore was of little consequence long-term to wildlife, these assessments have not held up in the long term. From the paper:

[C]ontrary to claims of rapid recovery and limited long-term effects, ample evidence accumulated in the decades since the spill has demonstrated that not all injured species and ecosystems recovered quickly, with protracted recovery particularly evident in nearshore food webs… Sea otter population recovery rates in heavily oiled western [Prince William Sound] were about half those expected, and in areas where oiling and sea otter mortality were greatest, there was no evidence of recovery through 2000.

James L. Bodkin, et al. MEPS. DOI:10.3354/meps09523

James L. Bodkin, et al. MEPS. DOI:10.3354/meps09523

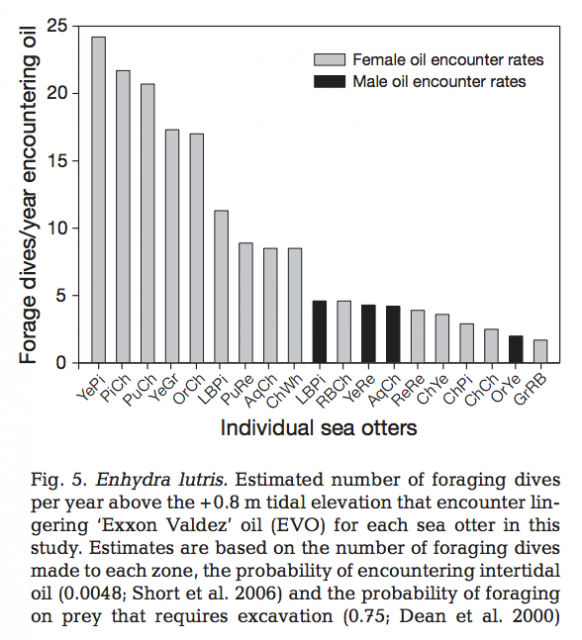

To get a better sense of why this might be, the researchers recorded the foraging behavior of 19 sea otters in waters where lingering oil and delayed ecosystem recovery have been well documented. They found that while otters can forage up to 302 feet (92 meters) deep, much foraging takes place in the more heavily-oiled waters of the intertidal zone. Here’s how that breaks down:

- Between 5 and 38% of all foraging was in the intertidal zone.

- On average female sea otters made 16,050 intertidal dives per year.

- 18% of the females’ dives were at depths above the 262-foot-deep (0.80-meter-deep) tidal elevation.

- Males made 4,100 intertidal dives per year.

- 26% of male intertidal foraging took place at depths above the 262-foot-deep (80-meter-deep) tidal elevation.

Joe Robertson via Wikimedia Commons

Joe Robertson via Wikimedia Commons

Overall, estimated annual oil encounter rates ranged from up to 24 times a year, with a conservative average of 10 times a year for females and 4 times for males.

Worrisomely, exposure rates increased in spring when intertidal foraging rates doubled and when females were nursing small pups. The problem apparently arises most from the otters’ habitat of digging in intertidal and subtidal sediment for clams:

Exposure levels [to oil] cannot be quantified, and the biological and ecological consequences of the exposure that results from the identified [clam-eating] path are difficult to assess and largely remain unknown. However, we now know that variation in individual and seasonal dive patterns means that some sea otters are much more likely to be exposed to oil than others. We also know that most exposure comes at a time of year when most adult females are giving birth, and that pups have few mechanisms to avoid or mitigate exposure to oil.

The open-access paper:

- Bodkin JL, Ballachey BE, Coletti HA, Esslinger GG and others (2012) Long-term effects of the ‘Exxon Valdez’ oil spill: sea otter foraging in the intertidal as a pathway of exposure to lingering oil. MEPS. DOI:10.3354/meps09523