<a href="http://www.flickr.com/photos/amylovesyah/51059">anylovesyah</a>/Flickr

Three Girl Scout troops in Louisiana won’t be hawking Thin Mints this year. They’ve disbanded in protest after the Girl Scouts of Colorado accepted seven-year-old transgender child Bobby Montoya as a member. Montoya was born a boy but has considered herself a girl since she was two years old, says her mom Felisha Archuleta. In October, Archuleta took her daughter to speak with a Denver troop leader about signing up, and took her daughter away crying after the Scout leader referred to the child as “it” and said “Everyone will know he’s a boy.” Three weeks later, the statewide Girl Scouts body issued a statement saying, “If a child identifies as a girl and the child’s family presents her as a girl, Girl Scouts of Colorado welcomes her as a Girl Scout.” When they heard about this reversal, three moms and troop leaders in St. Tammany Parish, Louisiana decided to dissolve their troops and leave Girl Scouts.

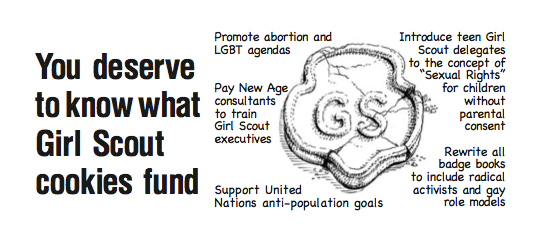

Now, 95 years after the organization first starting selling cookies, its signature product has once again become a political pawn. Right-wing groups and some conservative parents and scouts have posted to a site called Honest Girl Scouts, YouTube, and Facebook pages—including one called “Make Girl Scouts Clean Again“—urging Girl Scouts everywhere to go on strike from selling cookies, and their parents to stop buying them. They want Girl Scouts USA to officially bans transgender children from membership, and kick out any known transgender scouts “hiding” in the troops.

One of the former Louisiana troop leaders, a mother at Northland Christian School in Lacombe, told the Baptist Press that by letting Bobby Montoya join, the organization had created an “almost dangerous situation” for other children. Girl Scouts Louisiana East put up a new policy on its website saying transgender children wouldn’t be allowed to join if they tried to apply there—as far as they know, none ever have. A video by a 14-year-old Girl Scout from Ventura, California, identified only as Taylor, was uploaded to YouTube Honest Girl Scouts, with Taylor reading off a script urging fellow Scouts to go on strike, claiming the Girl Scouts was putting girls in physical danger during sleepovers and field trips by allowing “transgender boys” to be there, and not letting the other girls know. “Unfortunately, I think it is because GSUSA cares more about promoting the desires of a small handful of people than it does for my safety and the safety of my friends and sister Girl Scouts, and they are doing it with money we earned for them from Girl Scout cookies.” The video received 387,000 hits before the poster marked the video “private,” blocking it from the general public.

From a flier on the website HonestGirlScouts.com

At this stage, the proposed boycotts are unlikely to have much effect on the organization’s bottom line. Last year, Girl Scouts USA sold 198 million boxes for a record $714 million in profits, and despite what some urging the boycott seem to think, the national governing body doesn’t actually pull revenue from local cookie drives; it makes money through membership dues, which are $12 a year per girl, and from contributions from foundations, corporations, and private individuals. Thirty percent of cookie profits go back to the two bakers that GSUSA has contracted with, and the rest are shared between local troops and 100 regional councils across the country—there’s about two per state—so revenue from the cookie drives more or less stays in local communities. The national body charges the bakers a licensing fee for use of its brand on the cookie boxes, and says the proceeds go back to local scouts by way of materials and support.

So what badge are they earning here, exactly? Source: rich701/flickr

So what badge are they earning here, exactly? Source: rich701/flickr

Beyond organizing cookie sales, local troop leaders and regional directors exert a surprising amount of autonomy over troop activities and membership decisions. While a Scout leader somewhere in upstate New York might decide to sponsor a sex-ed forum hosted by the local Planned Parenthood branch, a local leader in Chatanooga might sponsor abstinence-oriented activities instead. The national organization provides very little in the way of agenda-setting or cultural cues, beyond its ideologically flexible messaging about “empowerment, “paths to success,” and reaching one’s full potential.

So far, the national Girl Scouts USA has made no official statement about Bobby Montoya’s case or what happened in Louisiana. Spokeswoman Michelle Tompkins made it clear to me that the Colorado council’s decision to let Montoya join doesn’t equate to a nationwide policy of including transgender children. The organization’s troop-wide “Inclusion and Nondiscrimination Policy” calls for adapting activities to serve “??girls who have special needs, including those who have physical or development disabilities,” but also goes on to say that “sexual orientation is a private matter for girls and their families to address…Girl Scouts has established standards that do not permit the advocacy or promotion of a personal lifestyle or sexual orientation.”

Hungry? Source: Library of Congress

Hungry? Source: Library of Congress

So what does all this mean for the next Bobby Montoya who wants to be a Girl Scout? Andrea Bastiani Archibald, a development psychologist with Girl Scouts USA, says it’s a case-by-case decision. “It depends on the age of the child and other questions: Are they being recognized everywhere (as girls)? Are there policies in place at that child’s school? Are they attending a girl’s bathroom?” She reiterated that acceptance of transgender girls is not formal Girl Scouts policy, and that the organization takes a position of nondiscrimination rather than radical inclusion. So for all intents and purposes, decisions on who gets included or excluded play out at a local level.

Bobby Montoya’s case isn’t the first time local troopers and families have clashed with the parent organization over issues of feminism and inclusion. In May of 2011 the Christian Post reported that sisters Sydney and Tess Volanski quit their troop after eight years because they believed the organization was “promoting Planned Parenthood, promiscuity and abortion to their members.” Tensions between local communities and the national body go way back. In 1984, local troops in Detroit cancelled hundreds of cookie sales over a proposed sex-education program that included discussions on birth control and abortion. In 1947—seven years before Brown vs. Board of Education—Southern troops were “absolutely outraged” when Girl Scouts USA sent all of its troops new handbooks that included images of African-American girls, and some even sent the books back, according to Mary Rothschild, a historian who’s been studying the Girl Scouts for 25 years. “I was a Brownie in the early ’50s, and I remember all of these sketches and illustrations—they were all integrated,” she recalls.

The cookie strike over Bobby Montoya isn’t even the only one underway right now. Austin and Cathy Ruse of the Catholic Family and Human Rights Institute told the Christian Post yesterday that they’re calling for another public boycott over the organization’s ties to Planned Parenthood, asking people to “forgo the Thin Mints this year because of the far-left sociopolitical agenda pushed by Girl Scouts HQ.”

Still, the Girls Scouts marks its 100th anniversary this year, with 2.3 million troopers and 880,000 adult, mostly volunteer mentors across all 50 states. It’s a remarkably cohesive organization, and Girl Scouts have often been ahead of the curve, if just by a hair, on hot-button cultural issues. “They’re consistently and quietly moving the great moderate American middle in progressive ways,” says Rothschild. “They were trashed for internationalism in the McCarthy period. The American Legion tried to get parents to take their children out of Girl Scouts because they were a ‘proto-Communist organization’ for being in favor of the United Nations, and advocating that girls learn about Latin America to earn World Citizen badges.” In 1975, a Catholic archdiocese in Philadelphia cut off most of its support for the Girl Scouts over its “To Be a Woman” badge program, which had scouts discussing pregnancy, birth control, and abortion.

Think they cooked that over the campfire? Source: Library of Congress

Think they cooked that over the campfire? Source: Library of Congress

Despite this history, Girl Scouts’ leadership is quick to distance the organization from claims of radicalism. “We can’t be radical, we take no political position,” says Bastiani Archibald, the GSUSA developmental psychologist. “We are really so moderate. To many just the concept of girls or women in leadership is a radical notion.”

Focus on the Family, Family Research Council, and Concerned Women for America couldn’t disagree more. In the past decade, these conservative groups have ramped up their vitriol against the Girl Scouts, making GSUSA a regular target on their websites, Fox News appearances, and right-wing radio broadcasts. They rail against Girl Scouts’ participation in sex-education programs, religious tolerance, and for allowing gays and lesbians to serve as troop leaders. Commenting on the news of Montoya’s inclusion, Tony Perkins, president of the Family Research Council said, “I’m guessing most parents didn’t enlist their daughters in the Girl Scouts to spark conversations about gender identity. I know these are Brownies, but exposing them to these issues is a little nuts.”

Source: Library of Congress

Source: Library of Congress

To provide an alternative, in 1995 a former Girl Scout founded a rival faith-based organization called American Heritage Girls, billing itself as “the premier national character development organization for young women that embraces Christian values and encourages family involvement.” The organization also earned a “memorandum of mutual support” from Boy Scouts of America (which famously bans openly gay adults and teenagers from jobs and volunteer positions with BSA), the first time Boy Scouts have partnered on the national level with an all-girls’ organization. According to its website, the organization has 20,000 members in 44 states and four countries. “Over 90 percent of the people who come to us have left the Girl Scouts—we’re like the best kept secret,” says founder Patti Garibay. The former troop leaders who disbanded Girl Scouts in Louisiana say they’re now looking to bring their flock to the American Heritage Girls.

So could the campaign against Montoya actually hurt cookie sales? The transgender community and others outraged by the issue have taken to social media, urging people to buy up Caramel deLites by the caseload this year in support of transgender girl scouts. “I’m a vegan but this makes me want to buy a box of girl scout cookies or twenty boxes,” tweeted @Stella_Zine, and a Twitter search for “Girl Scout cookies” turns up hundreds of similar messages. As The Atlantic reported, Gothamist instructed its readers to “start buying ALL THE GIRL SCOUT COOKIES EVER,” and transgender adult film performer Buck Angel, who says he’s a former Girl Scout, put out a YouTube video about his happy memories as a Girl Scout. “They accepted me into the Girl Scout troop and everyone was loving and giving. It was never an issue. It’s not about anything other than showing love and respect and learning how to be a good person.”

As of earlier this week, Montoya still hadn’t joined her local Denver troop. After the statement from Girl Scouts of Colorado in October, Montoya’s mother told ABC that she wants an official apology from the organization, and for Montoya to have a different troop leader than the one who referred to the girl as “it” when she first tried to apply. Still, Archuleta said, Montoya came out of the experience stronger. Before, she had dressed as a boy in school. Now, she dresses as a girl. “‘Mom, you are right,” Montoya told her mother. “They can’t be mean to me. I am a human being like everyone else.”