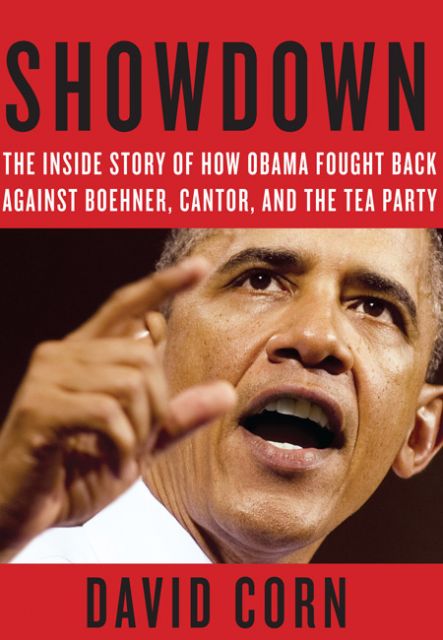

As some readers may already know, my new book, Showdown: The Inside Story of How Obama Fought Back Against Boehner, Cantor, and the Tea Party (William Morrow) comes out soon. The book is a behind-the-scenes narrative covering the White House from the disastrous 2010 midterm elections until the promising start of 2012. It is a reporting-driven tale of how President Barack Obama got his groove back in time for the reelection campaign. The book chronicles the president’s lame-duck session victories (a second stimulus, repealing Don’t Ask/Don’t Tell) and the subsequent agonizing budget and debt-ceiling battles, while providing fly-on-the-wall coverage of Obama’s handling of the uprisings in Egypt and Libya and the Osama bin Laden mission. It depicts what was happening within the Oval Office as Obama, following the debt-ceiling debacle, moved toward a more populist and confrontational stance against the tea party GOPers to set up the titanic 2012 contest. The book—based on interviews with White House officials, members of Obama’s inner circle, and Republicans and Democrats on Capitol Hill—is a probing examination (and explanation) of the man at the center of the national political vortex. You can, of course, preorder Showdown and find out more on Facebook. [UPDATE: Showdown has been released. It can be found in bookstores and ordered here.]

As some readers may already know, my new book, Showdown: The Inside Story of How Obama Fought Back Against Boehner, Cantor, and the Tea Party (William Morrow) comes out soon. The book is a behind-the-scenes narrative covering the White House from the disastrous 2010 midterm elections until the promising start of 2012. It is a reporting-driven tale of how President Barack Obama got his groove back in time for the reelection campaign. The book chronicles the president’s lame-duck session victories (a second stimulus, repealing Don’t Ask/Don’t Tell) and the subsequent agonizing budget and debt-ceiling battles, while providing fly-on-the-wall coverage of Obama’s handling of the uprisings in Egypt and Libya and the Osama bin Laden mission. It depicts what was happening within the Oval Office as Obama, following the debt-ceiling debacle, moved toward a more populist and confrontational stance against the tea party GOPers to set up the titanic 2012 contest. The book—based on interviews with White House officials, members of Obama’s inner circle, and Republicans and Democrats on Capitol Hill—is a probing examination (and explanation) of the man at the center of the national political vortex. You can, of course, preorder Showdown and find out more on Facebook. [UPDATE: Showdown has been released. It can be found in bookstores and ordered here.]

Below is an excerpt from the book, released by the publisher. Other excerpts will be out in the coming days. Look for details about those on Twitter and Facebook. (A more booklike version of this excerpt can be found here.)

Chapter Ten: Mission Accomplished

Everyone was laughing.

President Obama was standing at the podium in the main ballroom of the Washington Hilton, addressing the tuxedo-and-gown crowd at the White House Correspondents’ Association dinner on the last Saturday night of April 2011.

The annual event is mockingly referred to as Washington’s prom, and each year thousands of journalists, government officials, politicos, and a smattering of Hollywood celebrities gather to drink, eat, schmooze, observe, and be observed. Most years, the president attends and is compelled to perform like a stand-up comic. Obama had the assembled in stitches.

The president was targeting his best jabs at Donald Trump, the celebrity billionaire then flirting with joining the race for the Republican presidential nomination. Trump had leaped into the fray waving the banner of the birthers—those conservative Obama foes who claimed the president had actually been born in Kenya, rather than in Hawaii, thus making him ineligible to be president.

This outlandish charge had dogged the president since the campaign—even though the state of Hawaii had issued a routine certification of birth proving that Obama had been born there. (Birth notices in two local newspapers from the time also confirmed this.) The birthers’ conspiracy theory reflected a predominant theme within the conservative opposition: Obama was the other—somehow not quite a real American who truly understood and treasured the nation.

Birtherism had long lost steam, but Trump had revived the cause. He spent weeks repeatedly raising questions about Obama’s birth and called on the president to make public his original long-form birth certificate. Sarah Palin endorsed his effort. Recent polling indicated that 45 percent of Republicans believed Obama had been born in another country.

Then on April 27, Obama strode into the White House press briefing room to announce he was releasing his long-form birth certificate, which showed—surprise, surprise—that he was Hawaiian born.

“We do not have time for this kind of silliness,” Obama remarked. “We’ve got better stuff to do. I’ve got better stuff to do.” And he took a sharp poke at Trump: “We’re not going to be able to solve our problems if we get distracted by sideshows and carnival barkers.”

Pundits immediately questioned whether Obama had finally relented to the birthers’ call because the White House was worried that the issue, thanks to Trump, was gaining traction. White House officials’ simpler explanation was that Obama had just had enough.

The week Obama gave his speech at George Washington University, challenging the Republicans on economic policy, he had been disheartened to see Trump and his birther claims draw so much attention. That’s it, he thought. He instructed his attorney to contact Hawaii and request a copy of the long-form certificate. And Obama decided that he would make the official announcement before the television cameras.

“He wanted to deliver the overall message to the media and the public that we ought to focus on the real stuff,” a White House aide said.

Trump declared he was “very proud of himself” for having compelled Obama to produce that document. (Some birthers would insist the certificate had been forged.) But Obama would literally have the last laugh.

At the dinner, three days later, the president was pummeling Trump—with gags.

“No one is happier, no one is prouder to put this birth certificate matter to rest than The Donald,” Obama quipped. “And that’s because he can finally get back to focusing on the issues that matter—like, did we fake the moon landing?”

Referring to an episode of Trump’s reality television show, Obama cracked, “The men’s cooking team did not impress the judges from Omaha Steaks, and there was a lot of blame to go around. But you, Mr. Trump, recognized that the real problem was a lack of leadership. And so ultimately, you didn’t blame Lil’ Jon or Meat Loaf. You fired Gary Busey. And these are the kind of decisions that would keep me up at night. Well handled, sir.”

The audience roared with laughter. Trump was at the dinner, a guest of the Washington Post, and practically everyone in the room was looking to see his reaction. He didn’t crack a smile. He appeared to be seething. There was a charge in the ballroom. It was as if a school bully were being called out in the middle of an assembly. In this instant, Obama was vanquishing Trump, birtherism, the silliness that often infects American politics, and the far Right’s ridiculous assaults on him.

In a day, though, this moment would seem sharper and deeper than the audience at the dinner realized, for as Obama was mocking Trump, he was anxiously awaiting the outcome of one of the most weighty decisions of his presidency—his order to send a team of US special forces into Pakistan to get Osama bin Laden.

Obama had made the final decision to launch this dangerous and daring mission the day before. And as he joked that Saturday night, the president and several aides—only a small number had been informed about the raid—realized the next day could mark the virtual end of Obama’s presidency if the operation went badly.

That Saturday morning, Denis McDonough brought an extra suit to work, just in case he’d be stuck at the White House for a few days. Valerie Jarrett learned of the possible raid only that day. She was nervous. She had wanted to stay home all day, but she forced herself to go to the correspondents’ dinner and the various parties and receptions before and after.

She remembered that a few days earlier she had been with the president in New York City for a fund-raiser. He was working the rope line, and a woman introduced herself, noting in a near whisper that she had lost a relative in the 9/11 attacks.

“Are we going to get bin Laden?” the woman asked.

Holding her hand, Obama replied, “We’re working on it.”

At the dinner, Bill Daley was sitting at the ABC News table. Next to him was Eric Stonestreet, a star on the network’s hit sitcom Modern Family. Stonestreet was excited because he was booked on a White House tour the following day.

At one point, Stonestreet checked his e-mail, and his face registered dejection.

“Oh shit,” he muttered. The tour was canceled. He looked to Daley for an explanation. Daley didn’t tell the actor that he was the one who had called off the tours for the day. He didn’t want tourists in the White House at a time of potential crisis.

“Maybe a pipe burst,” Daley said.

During the 2008 campaign, Obama had bluntly vowed,”We will kill bin Laden.” In the spring of 2009, the president wondered if the hunt had slipped off the front burner.

Consequently, in June 2009, he sent a memo to Leon Panetta, the new CIA chief, stating that he considered finding bin Laden a high-priority task. He requested a detailed operation plan for locating and “bringing to justice” the al-Qaeda leader.

In the months that followed, Obama would receive an occasional briefing on the search for bin Laden. But there was never any information of consequence—until the summer of 2010. The president was told about a compound of interest in Abbottabad, Pakistan, about 35 miles north of Islamabad, a suburban and affluent area that was home to a Pakistani military academy. OBL might be there.

In the years after the 9/11 attacks, US military and intelligence officials interrogating suspected terrorist detainees continuously sought information on individuals who might be assisting bin Laden. As a result, they learned of a courier who was said to be trusted by bin Laden and who had been a protégé of Khalid Sheikh Mohammed. But all they had was the man’s nom de guerre.

For years, the CIA tried—and failed—to determine his true identity and location. Then in 2007, the CIA discovered his name—Abu Ahmed al-Kuwaiti. Two years later they identified areas in Pakistan where he and his brother operated. But both men utilized extensive security measures to cloak their actions and whereabouts; this intensified the CIA’s interest in them but made it harder to find either of the two.

In the summer of 2010, US intelligence intercepted a telephone call between al-Kuwaiti and another operative being watched by the CIA. They located al-Kuwaiti and his brother and tracked them to the Abbottabad compound.

Intelligence analysts were stunned when they received details of the residence. It was much larger than nearby homes, and there were extensive security features. The main building had few windows facing outside, and it was ringed by 12- to 18-foot security walls topped with barbed wire. Residents of the compound burned their trash rather than placing it outside for collection. It seemed to have no phone or Internet service. The two brothers, who were living there, had no source of wealth. The place appeared custom-made for a “high-value target.”

And a family matching a description of the bin Ladens was living within the compound. The analysts concluded there was a good chance this was bin Laden’s home.

In a meeting so secret that White House aides did not e-mail about its subject, Panetta informed Obama, Joe Biden, Robert Gates, and Hillary Clinton about the compound, and he showed the president an image of the residence. The atmosphere was electric. Finally, after all these years, they had a bead on bin Laden.

At this point, Obama couldn’t do much more than wait for the spies to do their jobs and gather more intelligence. But the president did start thinking about options. During the presidential campaign, he had repeatedly pledged that he would move unilaterally, if necessary, against “high-value terrorist targets like bin Laden” in Pakistan.

Hillary Clinton had chastised him for talking recklessly. John McCain had derided Obama for announcing that “he’s going to attack Pakistan.” Now, Obama was close to being able to make good on his promise.

The CIA continued to pursue more intelligence, looking for incontrovertible evidence. Satellites snapped high-resolution photographs of the compound; eavesdropping equipment was trained on it in an attempt to record voices inside.

From the start, a paramount concern for the White House and the CIA was security. No one wanted the slightest word of this to leak. Just a handful of Obama’s national security aides were informed about the lead on bin Laden.

Obama and his top national security advisers feared that if even the most vague reference reached the media—say, a newspaper reported that the CIA had stepped up the hunt for bin Laden—a for sale sign would immediately appear outside the Abbottabad compound. Obama would not even discuss the operation at his biweekly counterterrorism meetings with cabinet officials.

The CIA, working with other intelligence agencies (including the National Security Agency and the National Geospatial-Intelligence Agency), continued to gather intelligence on the compound, and even as the agency’s analysts became increasingly convinced that bin Laden was there, they always had doubts. Perhaps it was the home of a Dubai prince lying low—or Afghan Taliban chief Mullah Omar, or al-Qaeda No. 2 Ayman al-Zawahiri.

The president and a few of his aides tracked the CIA’s work, and by mid-February 2011, they concluded the intelligence was strong enough to start planning a mission.

Panetta brought Vice Admiral William McRaven, the commander of the military’s Joint Special Operations Command, to CIA headquarters to tell him about the compound. McRaven was the military’s top expert in covert warfare. He and his senior aides at JSOC immediately began cooking up various options for a secret assault.

Over the course of several weeks, McRaven developed three basic COAs—courses of action. A massive bombing strike in which B-2 stealth bombers would drop several dozen 2,000-pound, GPS-guided bombs and obliterate the entire compound; a helicopter raid mounted by US commandos; or a joint assault with Pakistani forces, who would be informed of the operation only shortly before its launch.

It was getting real. As Obama contended with the challenges of the Arab Spring, the frustrations of budget negotiations with the Republicans, and the barely improving economy, he was thinking about achieving the biggest victory in the so-called war on terrorism (a phrase his administration rarely used). He could be the president to take down the nation’s number one enemy.

In mid-March 2011, Obama convened a series of National Security Council meetings on the bin Laden operation. At the first, on March 14, Panetta presented Obama with the three COAs. According to a participant, the president had “a visceral reaction” against this bombing strike because collateral damage would likely extend beyond the compound into the surrounding neighborhood. The CIA had already determined that the compound contained a number of women and children.

Another drawback of such an attack was that it would leave behind only rubble—and the remains of 20 or so people mixed in with the concrete and steel. In all that wreckage, could they find a piece of bin Laden—hair or flesh—for DNA analysis?

“The question was, would you accrue the strategic benefits of getting bin Laden if you couldn’t prove it?” Ben Rhodes recalled.

It could take several months for the intelligence community—by monitoring chatter in the al-Qaeda network or other means—to confirm bin Laden’s demise.

“And what could be worse,” Nicholas Rasmussen, the White House senior director for counterterrorism, later noted, “than OBL survives and comes out and says, ‘The United States failed to kill me’?”

Obama all but scratched this option off the list. He did ask the military to consider a surgical strike targeting the specific person living within the compound whom intelligence analysts suspected was the al-Qaeda leader. The analysts had dubbed him “the pacer,” for he would stride around the compound as if for exercise.

The CIA had not been able to obtain physical evidence that confirmed the man was bin Laden. But the National Geospatial-Intelligence Agency, which analyzes overhead imagery, had determined this fellow was between five-foot-eight and six-foot-eight. Far from definitive. And he might be a decoy.

But if they targeted him with a drone missile strike, would they really know it was bin Laden?

The president appeared to be leaning toward a man-on-man assault. He pressed McRaven on the details. How much training time would a squad need? How could the commandos make a positive identification of bin Laden?

Gates and others, though, were skeptical—or, as one participant later recalled, “keenly focused on the risks associated with a helicopter raid.” Gates had been at the CIA during Desert One (the failed mission President Jimmy Carter had approved to rescue American hostages held in Tehran in 1980) and Black Hawk Down (the 1993 operation in Somalia that fell apart and resulted in the deaths of 18 US troops). Another high-risk helicopter raid—this time flying undetected 100 miles into another country—was worrisome to him.

Obama and his aides dismissed a joint raid with the Pakistanis. They simply could not trust them. US officials had long suspected Pakistan’s Inter-Services Intelligence of routinely tipping off the targets of US actions, including drone strikes.

If bin Laden was indeed in the Abbottabad compound, it was hard to believe that no Pakistani military or intelligence officials knew he was there. Perhaps there was a way to work with the Pakistanis: If Washington on the morning of a planned attack contacted Pakistan’s top military chief, General Ashfaq Parvez Kayani, and essentially forced him to join the raid on a moment’s notice. Still, Obama did not believe any other nation, let alone Pakistan, could be trusted with advance information of an assault.

Soon afterward, officials reported back to the president that a surgical strike would require a large amount of ordnance. That is, it wouldn’t be all that surgical. A helicopter raid appeared the only viable choice.

As the planning meetings proceeded—the president and his aides often had a model of the compound before them—a critical point about a unilateral US assault caught Obama’s attention: How would these covert warriors return safely from the compound, especially if they were to encounter hostile Pakistani military forces? He noticed that in the initial planning the assault force was small. He asked McRaven if such a force could fight its way out if necessary.

McRaven had based the planning on an assumption that if his commandos were confronted by the Pakistanis, they would protect themselves without attempting to defeat the Pakistani forces, while waiting for the politicians in Washington and Islamabad to sort things out. He calculated that his team could hold off any Pakistani assault for one or two hours.

Obama nixed the idea of commandos hunkering down to await diplomatic rescue. He worried that the Navy SEALs conducting the mission could end up as hostages of the Pakistanis, and he told McRaven to ensure that the US forces could escape the compound and return to safety, whether or not they encountered Pakistani resistance.

“Don’t worry about keeping things calm with Pakistan,” Obama said to McRaven. “Worry about getting out.”

McRaven added additional forces; a second group of SEALs would be prepared to take on any Pakistani forces that might try to intervene.

The pace of the meetings in the White House—still involving merely a few aides—and at the CIA and JSOC picked up.

Throughout April a team of Navy SEALs from the elite and supersecret Team 6 unit (which was developed in response to the Desert One debacle) practiced for the assault, using a site built to resemble the compound. From a safe house it had set up earlier in Abbottabad, the CIA continued to watch the compound.

On the evening of Thursday, April 28, shortly after announcing that Panetta would succeed Gates as defense secretary, the president convened what would be the last NSC planning meeting on the bin Laden operation. McRaven was already in Afghanistan, ready to launch the raid if so ordered. Security concerns prevented him from being looped into the meeting via video.

Mike Mullen described the latest plans. In response to Obama’s demand for a fight-your- way-out plan, McRaven had added two Chinook helicopters to complement the pair of MH-60 Black Hawk stealth copters. And the SEALs had been instructed to be prepared to engage if they were met by the Pakistani military.