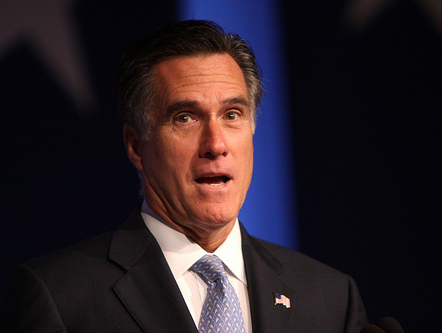

Presumptive GOP presidential nominee Mitt Romney<a href="http://www.flickr.com/photos/22007612@N05/6468740405/">Gage Skidmore</a>/Flickr

As governor of Massachusetts, Mitt Romney championed what he called a “no regrets” policy on climate change. He came into office vowing to eliminate the state’s SUV fleet and to close its dirtiest power plant. In 2004, his administration outlined a sweeping long-term vision for cutting the state’s emissions, improving efficiency, and promoting sustainable development that was considered among the most aggressive in the country.

That was then. As with his positions on other hot-button issues, Romney’s stance on global warming shifted after he started making plans to enter the 2008 presidential race. He went from stating that global warming is real and “human activity is a contributing factor” to declaring “we don’t know what’s causing climate change.” So what does the presumptive GOP nominee really believe? And how would he address climate change if elected president? One person who may well know is Gina McCarthy, who Romney tapped for top environmental posts in Massachusetts. But these days she’s not talking—presumably because she’s working for President Barack Obama as a top-ranking political appointee at the Environmental Protection Agency. Yes, Romney once handed his state’s environmental portfolio to a woman who now handles climate change matters for Obama.

As the assistant administrator for the Office of Air and Radiation, McCarthy is the top air quality regulator in the Obama EPA. In that post, she has been behind some of the administration’s toughest policies to cut greenhouse gas emissions, smog, and mercury pollution.

A Boston native, McCarthy worked under four previous Massachusetts governors before Romney. Shortly after taking office, he elevated her role, promoting her to undersecretary for policy at the Executive Office for Environmental Affairs. When Romney combined that agency and others into a superagency known as the Office for Commonwealth Development, he chose McCarthy to serve as its deputy secretary of operations.

In that role, McCarthy excelled, according to environmentalists in the state. “She was terrific—plainspoken, smart, and very aggressive,” says Jack Clarke, the director of public policy and government relations at Massachusetts Audubon and a member of several advisory panels to the Romney administration.

To head the new Office of Commonwealth Development, Romney appointed the respected environmental lawyer Douglas Foy, who had headed the Conservation Law Foundation. This office was responsible for many of Romney’s most progressive policies as governor, championing smart growth planning, mass transportation initiatives, and sustainable development. The office channeled state funds to towns and cities that promoted high-density housing and transit-oriented development, and it crafted a 20-year “Strategic Transportation Plan” that focused on public transit.

But the office’s highest profile work was on the state’s Climate Protection Plan, which Foy has touted as among the “most comprehensive” in the nation. Released in May 2004, it included dozens of policies, proposed laws, and incentive programs to bring the state’s emissions down to 1990 levels by 2010. It proposed to reduce emissions enough to “eliminate any dangerous threat to the climate” in the long term. When he unveiled the plan, Romney extolled the environmental and economic benefits for the state.

The Office of Commonwealth Development also played a key role in efforts to develop a pact between Northeastern states to cap and cut the emissions, known as the Regional Greenhouse Gas Initiative (RGGI). But in December 2005, Romney abruptly bailed on the pact, announcing his change of heart the same day he declared he was not seeking reelection as Massachusetts governor, a clue that he was prepping for a presidential run. Foy resigned two months later, and the governor’s office eventually released an alternative plan for cutting power plant emissions that was far more favorable to polluters. By the time Romney left office, the state actually had more SUVs in its fleet than when he took office.

By that point, McCarthy had left the Massachusetts government for a higher post. In 2004, she was appointed to serve as the head of Connecticut’s Department of Environmental Protection, under another Republican governor, Jodi Rell. There, she was vital in getting Connecticut to sign on to RGGI and earned high praise from both the governor and environmentalists. Given her background, it was not surprising that Obama appointed her to serve as a top-ranking EPA official in 2009.

McCarthy has been behind some of the Obama administration’s most aggressive air quality policies. In July 2011, the office finalized a new Cross-State Air Pollution Rule, which requires drastic reductions in sulfur and nitrogen oxide emissions from power plants. In December, the agency issued new national standards for mercury and other air toxins from coal-fired power plants that the EPA believes will prevent as many as 11,000 deaths each year. Her office was also introduced the tough new rules on smog-causing ozone pollution that Obama put on hold last year. Many of these tough new rules riled Obama critics in the oil and coal industry.

In March, McCarthy’s office announced the first national limits on greenhouse gas pollution, requiring all new power plants to emit less than half of what the average facility currently churns out. The new rules likely mean that no new coal-fired power plants will be built in the United States any time soon. The move has been blasted as a “war on coal” by the industry and its supporters, and the Romney campaign also joined in on criticism not only of the new policy, but of Obama’s advisors.

Enviros have been pleased by her work at the EPA. “She is a total bulldog for getting the best policies we can, not only out of the administration, but out of Congress,” says Margie Alt, a Massachusetts resident and the executive director of Environment America.

Through an EPA spokesman, McCarthy declined to be interviewed about her stint in Massachusetts as a key Romney official. Her background in the Romney administration has inspired some EPA-loathing conservatives to worry that Romney’s agenda on environmental matters might not be all that different from Obama’s if he’s elected to the presidency. But Massachusetts enviros say that despite making some strong environmental appointments early in his administration, Romney’s interest in the issue petered out about halfway through his term—around the time he began eyeing a White House bid. In the end, Romney’s tenure was mostly a disappointment to environmentalists. “All policies end in the governor’s office,” says James McCaffrey, director of the Massachusetts Sierra Club. “Why were those people appointed if they couldn’t actually make any progress under the governor?”

Romney’s post-2005 disinterest in climate change and other environmental issues has morphed into outright disdain in the 2012 campaign. “I exhale carbon dioxide,” Romney said last year, knocking the EPA’s efforts to regulate emissions—that is, his former aide McCarthy’s efforts. “I don’t want those guys following me around with a meter to see if I’m breathing too hard.” With hot air like that, Romney’s not likely to tack back to his earlier support for climate change action—or to ask McCarthy to stay on and serve him once again.