A Labor Ready outlet in Sioux Falls, South Dakota, July 2006.oddsandwich/Flickr

This story was produced with support from the Economic Hardship Reporting Project.

It is still dark when I show up at the Labor Ready storefront in downtown Oakland, California, just a few blocks from the plaza where the Occupy crowd threw up its tents against the one percent. From the sidewalk, the place looks vaguely illicit, with minimal signage and floor-to-ceiling shades that remain drawn 24/7. Later, I will come to think of this as the company “look”—unwelcoming and easy to miss—often tucked alongside a check-cashing business or payday lender.

The office opens at 5:30 a.m., but job seekers start appearing an hour early, hoping to snag a top spot on the sign-in sheet. By the time I arrive, 20 people, all but one of them men, are already inside—the space is essentially a waiting room with a long counter—standing or slouching in white plastic chairs. Behind the counter sits an African American woman with short hair and a bearing that suggests a low tolerance for bullshit. “I can’t remember the last time I got eight hours sleep,” a bleary-eyed man behind me announces to no one in particular.

After signing in, I grab a chair from a stack in the corner and take a seat, studying a sign that implores me to be “true” and “passionate” and “creative.” In reality, passion and creativity have nothing to do with it. Labor Ready provides warm bodies for grunt work that pays minimum wage or thereabouts. “Here’s a sledgehammer, there’s the wall,” is how Stacey Burke, the company’s vice-president of communications, characterized the work to Businessweek back in 2006.

It’s not a pretty formula, but it works. With 600 offices and a workforce of 400,000—more employees than Target or Home Depot—Labor Ready is the undisputed king of the blue-collar temp industry. Specializing in “tough-to-fill, high-turnover positions,” the company dispatches people to dig ditches, demolish buildings, remove debris, stock giant fulfillment warehouses—jobs that take their toll on a body. (See “I Was a Warehouse Wage Slave.”) And business is booming. Labor Ready’s parent company, TrueBlue, saw its profits soar 55 percent last year, to $31 million, on $1.3 billion in sales. The Bureau of Labor Statistics predicts that “employment services,” which includes temporary labor, will remain among the fastest growing sectors through 2020. TrueBlue CEO Steve Cooper, who took home nearly $2 million last year, predicts “a bright future ahead.”

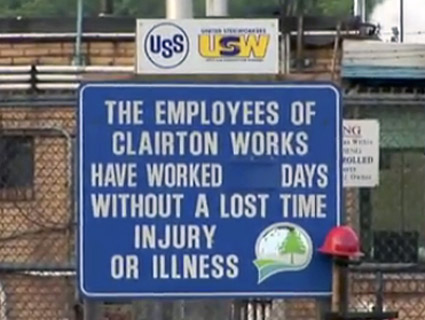

The woman behind the counter, whom I’ll call Natalie, turns on a television and pops in a video that job-seekers must tolerate every morning no matter how many times they’ve seen it. On the screen, a man who lost his arm in a workplace accident reminds us to be safe. A sign on the wall to my left states the number of consecutive days the branch has remained accident-free—330, which, given the physical nature of the work, almost seems too good to be true.

At one end of the room, a slender black man with a shaved head is leading an animated discussion of current events. “If it was a brother coming across the border, they would have sealed that shit up,” he says. The people around him nod. Someone comments that Latino immigrants have it easy.

“No, I wouldn’t say that,” the man responds. “Don’t forget: They have no recourse if they get hurt.” And “they get 10 bucks an hour, but the men picking them up on the corner are going to get 30 or 40 bucks an hour out of them.”

Labor Ready’s business customers are billed for the temp workers’ wages, plus fees that cover things like workers compensation insurance, payroll taxes, and, of course, a significant markup. The clients save cash on HR and training, and they save even more by eliminating the need for health insurance, paid sick leave, vacation time, and other standard employee benefits.

But for Labor Ready clients, perhaps the biggest advantage is that they get workers who are “flexible”—that is, dispensable. If you are unhappy with a Labor Ready worker “for any reason,” the company will replace that worker free of charge. And temps quickly learn to neither expect, nor ask for, raises, health care, or job security of any sort.

This low-cost arrangement, which leaves workers largely powerless, helps explain why more industries are turning to perma-temp workforces. According to the Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS), for instance, more than 15 percent of pickers, packers, movers, and unloaders—the warehouse workers who jump into action every time you order an item online—are temps. On average, they are paid $3 an hour less than their full-time counterparts.

Supplying cheap workers was Labor Ready’s mission from the day it launched in 1989. “We don’t encourage them to stay here,” company cofounder Glenn Welstad once admitted to a reporter. “If we paid them more money or if we provided them with benefits, they would have a tendency to stick around.”

Welstad was a farm boy from North Dakota who amassed a small fortune running a string of Hardee’s restaurants. When another of his numerous franchise efforts failed, he paid $50 for a name change—Dick’s Hamburgers became Labor Ready—and set about applying the principles of fast food to the temp market. He quickly opened a slew of cookie-cutter offices around the country, serving up cheap labor instead of burgers. The goal, in his words, was to become “the McDonalds of the temp industry.”

Welstad’s timing was ideal. During the 1990s, employers were developing an insatiable appetite for short-term labor to cut costs and respond to fluctuating demand. In the early 1980s, employment in the “temporary help services” industry—which covers both temp workers and employees of the firms that supply them—stood in the several hundreds of thousands. Now it’s 2.5 million, a seven-fold increase in less than four decades. By 2020, the BLS foresees more than 440,000 new jobs in the sector.

In the meantime, the temp craze has expanded from air-conditioned offices to warehouses and construction sites. In 1990, a year after Labor Ready was founded, clerical workers made up 42 percent of the temp workforce, with blue-collar workers comprising about 25 percent. By 2000, the numbers were flipped, a phenomenon driven by the outsourcing of American manufacturing jobs. In 1989, according to a forthcoming article in the Industrial and Labor Relations Review, only 1 in 43 manufacturing jobs were temporary. By 2006, 1 in 11 were.

As the prospects for stable blue-collar employment soured, Labor Ready’s sales soared. In 1991, it had eight stores and booked a modest $6 million in revenue. The company went public in 1998, and by 2000 it had nearly $1 billion in revenue and 852 offices, covering every state in the nation, plus outlets in Canada, Puerto Rico, and the United Kingdom.

Labor Ready had other trends on its side as well. Welstad credited welfare reform with dumping more cheap workers at his door: Depending on the state, somewhere between 15 and 40 percent of former welfare recipients found work as temps. It certainly didn’t hurt that people who’d gotten tangled up in the drug war were finding regular employment was hard to come by.

Soon after Labor Ready went public, it became a target of the AFL-CIO’s Building and Construction Trades Department, which was seeking to unionize temporary workers. “From a corporate campaign perspective it was like a dream come true,” remembers Will Collette, the lead researcher in the endeavor. In the end, the union gave up on Labor Ready. While high injury rates were documented in the company’s SEC filings, “workers were almost impossible to organize,” Collette says. “They were angry, but didn’t stick around. I’ve never seen a multinational company whose workforce turns over every 21 days.”

In 2000, CEO Welstad resigned abruptly after taking out an “unauthorized loan” of $3.5 million. While the loan was quickly repaid, the fallout left Labor Ready reeling, and it took a few years to regain its footing. In 2007, the company changed its name to TrueBlue, but it retained Labor Ready as its primary brand, which today accounts for nearly two-thirds of overall revenue.

Rather than continue Welstad’s aggressive expansion, which required severe cutbacks during recessions, current CEO Steve Cooper has instead focused on managing costs and diversifying: TrueBlue now owns four other small staffing companies specializing in industries like aviation and trucking, and is focused on landing big national accounts such as Walmart, which has utilized Labor Ready’s services. There’s also been a marked shift in public relations. At times, Welstad seemed hardly able to contain his disdain for temp workers—”The segment we deal with lacks discipline,” he told the Chicago Tribune. But Cooper now characterizes TrueBlue as a socially conscious firm dedicated to “changing the world by putting people to work.” Labor Ready, its website boasts, is the place for companies who need people that will put in “an honest day’s work for an honest day’s pay.”

After an hour spent cooling my heels at the Oakland storefront, I step outside to stretch my legs, and strike up a conversation with Darryl, who looks to be in his 40s and is wearing a Raiders sweatshirt and black beanie. (I’ve changed most names to respect the workers’ privacy, as I hadn’t yet revealed myself as a reporter.) Darryl tells me he’s struggled to find regular employment since he got out of jail. “I keep hoping and praying that something hits,” he says. “But people hear about being in jail and that’s the end of the conversation.” I don’t pry, but from other workers I will ascertain that their past crimes typically involve drug possession. Some mornings, half of the names on the sign-in sheet are from a nearby prisoner re-entry program.

Before working for Labor Ready, job seekers must complete a 73-question behavioral test to assess trustworthiness. I passed this test a long time ago when I worked briefly for the company in New York, so I’m already listed in its system as being behaved. Among other things, Labor Ready had asked me to list which drugs I’d recently consumed, to rate my proficiency at fighting with my fists, and to estimate the value of goods I’d stolen from previous employers during the last six months. I was half inclined to request a calculator.

By 9:30, I find myself alone in the Labor Ready office. The others have either been sent off to work, left to attend a class for parolees, or given up. I’m about to call it a day myself when Natalie motions for me. “You’ve got a car, right?” she asks. (I do, unlike many of the others.) She needs someone to get to a warehouse quickly to replace another Labor Ready worker. She hands me a pair of gloves and a work ticket. “It’s easy, doing cleanup.”

I make my way to an industrial stretch near the Oakland Coliseum and meet Chris, who manages a large warehouse along with several empty lots across the street. “I sent the other guy home,” he tells me. “I don’t know what happened, but his hand was all swollen.”

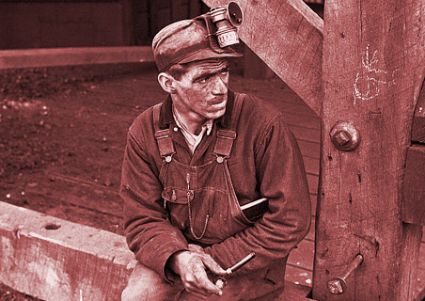

Chris hands me off to Hank, his 70-year-old assistant. It’s instantly clear who does the work around here. Chris is portly and soft, wearing a Hawaiian shirt and khakis. Hank is from Montana and looks it, or so it seems to a city boy: His angular face has deep creases from the sun and he wears a trucker’s cap, flannel shirt, and stained jeans. In a diner during election season, politicians would shove babies out of their way to score a photo-op with Hank.

Hank passes me to Leonard, another Labor Ready employee, who takes a break from shoveling to explain that we are moving a bunch of dirt from one lot to another. I pick up a shovel and start digging, soon falling behind the pace set by Leonard, who at 65 is more than three decades my senior. A retired handyman, he takes temp jobs to help cover the bills.

Several hours later, I’m standing atop an uneven mound of earth, perhaps seven feet high, struggling to anchor a tarp with large rocks. The wind whips dust into my face, but after a short struggle I secure the plastic. “This is nothing,” Leonard says. A black man with a stocky build and deep voice that frequently gathers steam into a rumbling laugh, he grew up in the California farming town of Tracy and started working the fields at 13. He’s harvested just about every crop the state has to offer, from lettuce to strawberries. “Now it’s all Mexicans doing the work,” Leonard says.

We shovel for a bit. “You ever heard of the ‘West Coast shorty’?” he asks presently. I shake my head. “Some people called it the short-handled hoe.”

The short-handled hoe, which California outlawed in 1975, was Leonard’s companion for years. The implement was infamous for destroying the backs of farmworkers, who were forced to stoop over the crops with their noses to the ground. Eventually, Leonard got a better job cutting sheet metal. The shearing machine didn’t have a safety guard, though, and when one day his knee bumped the button, the blade sliced off four of his fingers. No wonder he finds Labor Ready an easy gig: The man is a walking embodiment of the war on workers. “At least I got a settlement,” he tells me, “and the company had to put safeties on all their machines.”

By the end of the work day I’m exhausted and dirty; Leonard seems unaffected.

Back at the Labor Ready office, I have to wait nearly 30 minutes to receive my check. The job paid $8 an hour—minimum wage. For five hours of labor, I get $37.34 after taxes. I am not paid, however, for the four hours on call, or the time spent in transit to and from the job site, or waiting to get paid. None of this meets the legal definition of wage theft, but it sure feels like it. A large banner inside the office boasts, “Temporary Workers on Demand,” possibly the key selling point for Labor Ready clients. But for the workers, “on demand” is simply shorthand for lots of unpaid hours. For that matter, Labor Ready has been hit with a string of class-action suits over the years—including one filed last summer in New Jersey—alleging that it forced people to work off-the-clock, and failed to give them minimum wage and overtime pay.

Leonard, at least, avoids the waiting game on the front end, as the warehouse calls in a few days a week to request him. But he’s still only making half of his old handyman wage, and he tells me he rarely gets paid rest breaks—if true, a violation of California labor law. The company insists that it works with clients to ensure they comply with the law, and that a toll-free “care line” is available 24/7 for workers with concerns. Not that Leonard is complaining. “I get by,” he says. “I know I’m a cheap worker, but I’ve seen a lot worse.”

In the two weeks that I spend working out of Oakland’s Labor Ready branch, my “honest pay” tops out at $8.75 an hour. I’ll clean a yard for a trucking firm, scrape industrial glue from cement floors for a construction company, and screw on the caps of bottles at an massage oil company whose “Making Love” line is a bestseller. I’ll also move heavy tools for a multinational corporation that repairs boilers on ships and be asked to serve food at Oakland A’s games for Aramark, a $13 billion powerhouse. I wasn’t able to take that one, but if I had, I would have been earning $8 an hour next to unionized workers making $14.30.

Labor Ready’s Oakland workforce is nearly entirely black, excepting the branch manager, who is white. Most of the workers I talk to are searching for stability but finding it elusive. They include homeowners in foreclosure, apartment-dwellers who are being evicted, and residents of motels negotiating for a few more days. And many express hope they can parlay a temp gig into something permanent. “I’ve been with Labor Ready for over a year now and still haven’t had any luck,” says Stanley, who resembles a young Eddie Murphy. We’re standing in a dusty lot in Hayward, 15 miles south of Oakland, surrounded by 300 cars that have seen better days. “Most jobs are like this one, not looking to hire anyone full time.”

We’ve landed one of the more interesting Labor Ready assignments, a weekly charity auto auction. Six of us were hired to drive donated cars across the lot and idle under a canopy where used-car dealers make frantic bids and ask us questions like, “How’s the transmission feel?” After the bidding, we’re supposed to park the car and grab another. Several times, a vehicle I’m driving gives out as I attempt to pull away, at which point a forklift arrives and carries the carcass out of sight. I’ll drive cars that overheat, that refuse to shift into park or reverse, and that compel you to jump through the window Dukes of Hazard-style because the doors don’t open. “It’s a big risk,” a full-time auction employee tells me. “Buyers don’t know what they’re getting.” One buyer is excited that a car I’m driving has a full tank of gas.

I’ll meet a number of people who, like Stanley, have churned through a seemingly endless line of minimum-wage jobs. “They get stuck and then adjust to it,” says David Van Arsdale, a professor of sociology at Onondaga Community College in Syracuse, New York, who studies industrial temp agencies. As part of his research, Van Arsdale worked for three summers at Labor Ready, and rarely saw anyone land a permanent position. “Their whole lives get structured around the ephemeral nature of the work,” he says. “Companies use temps precisely to rid themselves of all the obligations of employment.”

The potential to convert a temp job into full-time employment is one of the benefits promoted by Labor Ready, but the company doesn’t actually know at what rate this happens. “I’d love to think future technology will track that,” says Stacey Burke, who is now VP of communications for parent company TrueBlue. Burke insists that Labor Ready helps workers along the path to permanent employment by giving them job connections and an employment history, thus making them more marketable. And if a company wants to make a temp worker permanent, they are not obliged to compensate Labor Ready. “We assist in the whole experience,” Burke says.

Yet there’s little evidence to support the claim that temp agencies help impoverished workers. In fact, a 2010 study by economists David Autor of the Massachusetts Institute of Technology and Susan Houseman of the Upjohn Institute for Employment Research found that temp jobs play a negligible—and if anything, negative—role in boosting people’s earnings. Looking at welfare-to-work participants in Detroit, the authors found that after a short spike in earnings, temp workers eventually saw a net decrease in income and employment, even when compared to workers who’d had no help securing work. Providing low-skill workers with a temp job, they wrote, “is no more effective than providing no job placements at all.”

From Oakland, I travel south to the Labor Ready branch in downtown San Jose, where I fill out another round of employment papers. As before, it’s a lengthy process. Labor Ready asks its laborers dozens of questions, including some that may help it qualify for tax breaks: Have you received food stamps? Are you a military veteran? Buried in the stack is a document I must sign that waives my right to sue over wage violations.

As I wait at the counter to hand over my papers, two men return from a job and turn in their time sheets. “You worked from 8:00 to 12:30, right?” asks the dispatcher.

“No, we were there at 7:30,” says one of the men, a muscular Latino who looks capable of knocking down a building in a single shift all by himself.

“But you started at 8:00, right?”

“Yeah, we started at 8:00, but they told us to be there at 7:30.” He’s growing agitated. “So we were there at 7:30.”

“Oh,” says the dispatcher, flashing an understanding smile. “They just wanted you to check in early. That’s all.”

The man grumbles but accepts the diminished paycheck and leaves. Dispatchers, after all, decide who works and who sits, so why make trouble over a few dollars?

Still, William Sokol, an employment attorney with law firm Weinberg, Roger, and Rosenfield, told me that what I witnessed is wage theft. “The law mandates that an employer is obligated to pay an employee when the employee is engaged to wait,” he says. “If the employer says, ‘Be at a certain place at a certain time so that you will be ready to work,’ the employer has to pay him.”

While it may only have been a half hour, those half hours can add up. The next morning, I show up for my first workday at the bustling San Jose office, where the phone rings off the hook and the staff hustles to fill available jobs. At 8 o’clock, I’m enlisted as part of a six-man team for a Friday-Saturday assignment, setting up exhibits for a beauty expo at a nearby convention center. This time, a different Labor Ready dispatcher tells us the score. “I don’t care if you get hit by a bus, you must be there—and be a half-hour early.”

The branch manager, a tanned middle-aged woman, nods her assent. “This is a very important account,” she says, sizing up the group for potential misfits.

We are but a small part of what will be a sizable Labor Ready contingent. Between the lot of us, the unpaid half-hours could easily exceed 16 hours over the two days. But in the end, I never make it to the jobsite: Riding my bike the next day, I get hit by a car and break my collarbone.

When I tell spokeswoman Burke what I saw, she initially sounds eager to investigate. “When we are wrong, we refresh people on the policy,” she says. “Our workers are owed money for every minute that they are asked to be on the jobsite. What you experienced is not prevalent because it’s not acceptable. Enough said.”

But when we speak again a few days later, Burke is less curious. “I don’t want to speculate,” she says, adding that I could have misinterpreted the situation. “The point is that we pay our workers for the work done. We train. We review. We reinforce. We train again. It’s a cycle of making sure we get it right.”

When I attempt to clarify—because what I saw seemed mighty hard to misinterpret—she interrupts. “Do you think that’s really the best use of this time?” she asks, and so we move on. She’s excited to talk about the ways the company “empowers” its workers, which includes a hotline that people can call to anonymously report problems. “It’s all about compliance,” she says.

The final Labor Ready office I visit is in Hayward, which is where I meet Joseph, a redheaded Brooklyn native who is wearing a fluorescent orange safety vest over a UCLA sweatshirt. At 51, Joseph has the solid build that comes from a lifetime spent putting buildings up and knocking them down. “I’m a jack-of-all-trades,” he says, with more than a hint of pride. “Demolition, framework, carpentry—you put me on any construction site and I know what to do.”

Joseph spent 16 years as a union laborer, pulling in $25 an hour plus benefits. When times were good he purchased a three-bedroom house for his wife and two sons. But when the economy tanked, his work through the union hall slowed to a trickle. He was finally forced to go on unemployment, and then that ran out. All the while he filled out countless job applications and fine-tuned his resume, but no one was hiring. Now, with a credit union preparing to foreclose on his house, he’s out of options. “They want $8,000,” he says. “Where can I get that kind of money?”

The two men standing next to Joseph share similar predicaments. One lost his union job in 2010 when the Toyota plant in nearby Fremont closed; another worked at a lumber yard that shed 15 people in 2009.

After waiting around for six hours, Joseph is finally dispatched to a warehouse where he’ll unload boxes of noodles. “If people see how I work, they might hire me,” he tells me hopefully. He’s feeling less optimistic the next morning, though. At the warehouse, he met another Labor Ready employee who had worked full-time at the site for more than a year and was still a temp. He shakes his head. “Companies know they can use Labor Ready to cut a buck.”

It’s a slow morning, so Joseph takes me to his house. Located at the end of a quiet cul-de-sac, it looks peaceful enough from the outside, a spacious and well-maintained two-story home with flowers in the front yard. But inside, where his 14-year-old son is preparing for school, the living room is empty and the kitchen shelves are bare. The credit union sent a notice threatening to evict the family within 72 hours, so Joseph moved all the furniture to in-laws. Boxes of Ritz crackers and Sprite are piled on the kitchen floor. “We’ve got enough food in the fridge for a few days,” he says.

Joseph grows quiet on the drive back to Labor Ready. “All I need is a real job,” he eventually says. “But now it seems everyone only wants temps.”

This story was produced with support from the Economic Hardship Reporting Project.