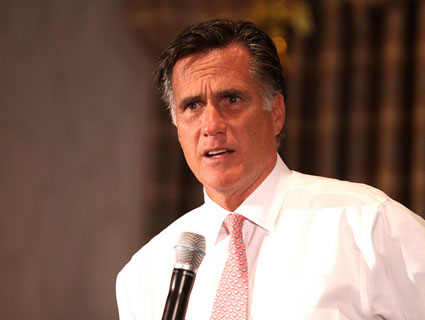

Mitt Romney speaks during the VFW convention in Reno, Nevada.Jose Luis Villegas/Sacramento Bee/ZUMAPRESS.com

When Mitt Romney was governor of Massachusetts he kept his distance from gambling. He turned down donations from the gaming industry for his privately underwritten inaugural gala. And though he initially supported allowing the establishment of slot parlors in order to close a $3 billion state deficit, he later announced he would not consider an expansion of gambling and decried the “social costs associated with gaming.” On the presidential campaign trail this year, Romney similarly declared that he opposed online poker because “of the social costs and people’s addictive gambling habits.” He explained, “I don’t want to increase access to gaming. I feel that we have plenty of access to gaming right now through the various casinos and establishments that exist.”

As a onetime bishop of the Mormon church—which opposes gambling, including state-sponsored lotteries—Romney’s lack of enthusiasm about legalized gambling is hardly surprising. Yet such reservations did not hinder him when he was a mega-financier. While Romney ran Bain Capital, the private equity firm he founded, he owned a Bain-affiliated investment fund that bet heavy on betting.

In March 1999, shortly after Romney departed Bain to run the 2002 Winter Olympics, Brookside Capital Investors Inc., a Bain-related entity wholly owned by Romney, filed a document with the Securities and Exchange Commission detailing the investments held the past quarter in its $559 million portfolio. On this roster were 1.2 million shares of GTECH Holdings Corp., then valued at $29 million. The company billed itself in its 1999 annual report as “a leading global supplier of systems and services to the lottery and gaming/entertaining industries.” This description put it mildly; Gtech was the world’s largest supplier of computer equipment for lotteries. It operated about 30 of 37 state lotteries in the United States, along with lotteries in England, Israel, Turkey, Australia, and other countries. It also was teaming up with big gaming firms to buy or revamp casinos and race tracks, adding and upgrading gambling equipment at these venues.

In 1998, Gtech had pulled in nearly $1 billion in revenue from its various gaming ventures. At the time Romney was investing in the firm, it was seeking to become a pioneer in Internet gambling.

The SEC filing reporting the Gtech investment doesn’t state when Romney’s Brookside Capital fund first purchased shares in the firm, but in the mid- and late-1990s the gaming company had a controversial reputation. In 1998, Guy Snowden resigned as head of the company a day after losing a bitter libel battle against billionaire Richard Branson, who had accused Snowden of trying to bribe him into withdrawing from a competition to run England’s national lottery. Reporting on Snowden’s departure, Fortune noted that “Snowden’s often sleazy, win-at-all-costs tactics…have helped make Gtech the dominant force in the computerized lottery business.” Snowden’s exit followed a run of Gtech scandals. In 1996, a top executive of the Providence, Rhode Island-based firm was convicted in New Jersey of fraud, bribery, money laundering, and conspiracy. (The exec had hired lobbyists to push for expanding the New Jersey lottery and had received kickbacks.) In Texas, where Gtech paid a well-connected lobbyist $3.2 million, there were also allegations of kickbacks and shady wheeling-and-dealing.

After Snowden lost his case against Branson, Gtech stock hit a low, and it might well have looked like a bargain to investors bullish on the long-term prospects of gambling, particularly online lotteries and Internet-based gaming.

Neither the Romney campaign nor Gtech responded to a request for comment.

These days, Romney takes a dark view of gambling. “Gaming has a social effect on a lot of people,” he told Las Vegas journalist Jon Ralston earlier this year. It could be that Romney’s view has been shaped by Mormon doctrine. After Romney offered to bet Texas Governor Rick Perry $10,000 during a debate last December to settle a dispute—and there’s no telling how serious Romney was—bloggers and reporters noted that gambling violated the precepts of the Mormon Church, which contends, “Gambling is motivated by a desire to get something for nothing. This desire is spiritually destructive.” But politics, too, might influence Romney’s position on gambling. From the mid-2000s on, as a potential or declared presidential candidate, Romney had an interest in courting conservative Christian voters who tend to oppose gambling.

Yet it’s complicated. During the 2012 campaign, even as Romney has declared his opposition to expanding online gambling, he has welcomed the hearty support of well-heeled casino magnates Donald Trump and Sheldon Adelson. And at Bain, he apparently was not opposed to investing millions of dollars in a prominent gambling multinational, despite its spotty reputation. If he had any concern about “the social effect,” it apparently was trumped by the profit motive.