Harold Ickes. Photo by Andrew CouncillHAROLD ICKES STEPPED OUT OF the car into the warm, salty Florida air and laid his eyes on a tableau of pure opulence. Surrounded by royal palm trees and hemmed in by the Atlantic on one side and the Intracoastal Waterway on the other, the 34,000-square-foot, $18 million estate, named Eastover, spanned three oceanfront lots. The coquina-stone Manalapan manse was built in 1929 for an heir to the Vanderbilt fortune; previous owners include Randolph Hearst and the onetime co-owner of the Indiana Pacers. Ickes ambled up the driveway and greeted the current owners, real estate magnate Franklin Haney and his wife, Emeline. Inside, Ickes noted the gold-painted ceiling in the foyer. “Twenty-two karat gold,” Haney said. “Came that way.” Later, over dinner, Ickes complimented the chandelier hanging over the dining room table—a gift, Haney said, from Winston Churchill, who stayed with the Vanderbilts on visits to the United States.

Harold Ickes. Photo by Andrew CouncillHAROLD ICKES STEPPED OUT OF the car into the warm, salty Florida air and laid his eyes on a tableau of pure opulence. Surrounded by royal palm trees and hemmed in by the Atlantic on one side and the Intracoastal Waterway on the other, the 34,000-square-foot, $18 million estate, named Eastover, spanned three oceanfront lots. The coquina-stone Manalapan manse was built in 1929 for an heir to the Vanderbilt fortune; previous owners include Randolph Hearst and the onetime co-owner of the Indiana Pacers. Ickes ambled up the driveway and greeted the current owners, real estate magnate Franklin Haney and his wife, Emeline. Inside, Ickes noted the gold-painted ceiling in the foyer. “Twenty-two karat gold,” Haney said. “Came that way.” Later, over dinner, Ickes complimented the chandelier hanging over the dining room table—a gift, Haney said, from Winston Churchill, who stayed with the Vanderbilts on visits to the United States.

Haney grew up dirt poor in McMinn County, Tennessee. He told Ickes how in the early 1930s the Tennessee Valley Authority, one of Franklin Delano Roosevelt’s lasting creations, had brought electricity to his tiny town. The first thing the Haneys did was dash out to buy a refrigerator to keep their ice cream cold. A dyed-in-the-wool Democrat who paid his way through college selling Bibles and once worked for Sen. Al Gore Sr. in Washington, Haney believed in the good government could do.

Haney also believed in the cause that had led Ickes to his doorstep: Priorities USA Action, the super-PAC backing President Obama and counterpunching the Republican attack ad blitzkrieg. Ickes says he didn’t get far into his usual pitch—that the ideal conditions for Obama’s 2008 victory aren’t present in 2012, that a handful of battleground states will decide the election, and that Republicans will spend every dime they can muster to beat Obama. “I get it, Harold,” Haney said. “This is a tight election.” Haney said he was in for a million, and maybe more down the road. His donation was among the super-PAC’s largest since it launched in 2011.

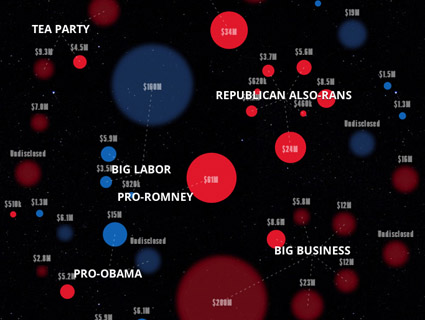

As Ickes jets around the country drumming up dollars to bolster Obama, he hasn’t had many meetings like that. Nor have his colleagues at Priorities USA Action or any of the other operatives raising money for Democratic super-PACs or other outside-spending groups. For the first time in modern history, an incumbent president may be outspent by his challenger, a fact Obama himself conceded in June. Republican and conservative super-PACs and nonprofits have pledged to spend as much as $1 billion to oust Obama and take full control of Congress. Mitt Romney’s campaign is projected to amass as much as $800 million on its own.

The Obama campaign, meanwhile, is on pace to raise $750 million or more, but when it comes to super-PACs and secretive nonprofit groups—which bankroll the sharpest attack ads—the Democrats are vastly outgunned. By late July, Priorities USA Action, the biggest super-PAC in Democratic politics, had taken in just under $21 million. Two related Democratic super-PACs, one focusing on the House and the other on the Senate, have banked even less. Around the same time, the pro-Romney super-PAC Restore Our Future announced it had raised more than $80 million. Karl Rove’s American Crossroads and Crossroads GPS boasted they had so far raised a combined $100 million—and that was back in April. In the outside-money chase, it’s not even close.

In early 2011, Sean Sweeney and Bill Burton, the former Obama White House aides who cofounded Priorities USA Action (a painfully bland name they settled on, as Burton told the New York Times Magazine, because their first 60 choices were already taken), enlisted Ickes to help close that gap. A fiery and highly respected Democratic operative who’s worked on more than a dozen presidential campaigns and inside the White House, Ickes is a savvy and dogged fundraiser with a reputation for pulling in big money—the kind of seven- and eight-figure checks needed to compete with Rove’s Crossroads groups and Charles and David Koch’s extensive donor network. His connections run deep in Washington and in the insular, prickly world of Democratic donors, especially Clinton supporters. Ickes served as deputy chief of staff in the Clinton White House and advised Hillary during her Senate and presidential campaigns; indeed, Ickes was tapped to plan her first Senate campaign on the same day in 1998 that the Senate dismissed the articles of impeachment against Bill. Clinton donors trust Ickes with their millions, and those millions are crucial to any outside Democratic effort.

Ickes, who turns 73 in September, works out of a sleek office near Dupont Circle that he and his longtime aide-de-camp, Janice Enright, share with a handful of lobbying and consulting shops. (Ickes and Enright have worked in the same room since their days in the Clinton White House.) His purple hounds-tooth shirt is open to the third button, and he occasionally pulls a comb through his thinning auburn hair. He closes his steel blue eyes when beginning a story, then opens them and stares into yours to make a point. He digresses easily and peppers his sentences with “fuck” and “bullshit.”

“He is a brilliant, take-no-prisoners, consummate political operative who has seen everything, done almost everything, and is still standing,” says Rob Stein, founder of the Democracy Alliance donor network. “There’s nobody like him in the Democratic ranks.”

Burton and Sweeney certainly seem to think so, having brought Ickes on to hunt for big donations. It’s a tall order, even for an experienced fundraiser. Loyal Democratic donors loathe the Citizens United decision and the Wild West campaign finance landscape it helped usher in, and they recoil from super-PACs. Some feel Obama hasn’t courted his donors sufficiently. Others simply aren’t yet fired up enough to write checks. Yet without that outside ammunition, Obama and congressional Democrats face the prospect of drowning in a deluge of Republican money. GOP super-PACs and nonprofits could wrest control of the Senate from the Democrats—and they could make the difference between a second Obama term and a Romney presidency.

Ickes grew up a political scion who hated politics. Born in Washington and raised on a 250-acre farm in Maryland, he is the son of Harold LeClair Ickes (“Old Curmudgeon” to his friends), FDR’s interior secretary, an architect of the New Deal’s Public Works Administration, and the longest-serving cabinet member in American history. Harold Sr. died when his son was 12. Harold Jr. barely graduated from the elite Sidwell Friends high school and then fled to the West. “I was running away from my father for years,” he told an interviewer in 1999. He put in a few years working on a dude ranch before earning an economics degree from Stanford. In 1963, he went south to join the civil rights movement. One day, while registering voters in Tallulah, Louisiana, a gang of shotgun-toting segregationists attacked him. The beating cost him a kidney.

It wasn’t until 1967, in the midst of the anti-Vietnam War movement, that Ickes entered the political fray by teaming with liberal activist Allard Lowenstein on a national “Dump Johnson” campaign. Ickes’ now-infamous temper flared early on: John Podesta, who would also go on to be a key Democratic strategist, recalls first meeting an irate Ickes at Eugene McCarthy’s Manhattan campaign headquarters in 1968. Podesta watched as Ickes, spewing profanities, hurled a chair against a wall, narrowly missing an open window looking out on Midtown. “I got in the habit of looking up for flying objects every time I’m in a room with Harold,” Podesta told me, chuckling.

Ickes worked on a slew of presidential campaigns—Jimmy Carter in 1976, Ted Kennedy in 1980, Walter Mondale in 1984, Jesse Jackson in 1988. “Harold has a Zelig-like way of being in all these fights,” says Democratic strategist Laura Quinn, who runs Catalist, the political data firm that Ickes helped found. Friends and foes alike describe Ickes as fiercely loyal—”Harold is the guy you want in the foxhole with you,” says former Democratic National Committee chairman Terry McAuliffe—and a tireless schemer always clawing for the slightest edge. “Harold can go longer and sleep less and just kill you,” says Anthony Corrado, a political scientist at Colby College who worked with Ickes on several campaigns going back to Mondale’s run.

Running Clinton’s New York operation in ’92 led to a position as deputy White House chief of staff. Ickes relished the chance to work on meaty policy fights, including health care reform. But before long Ickes, along with loyal aide Enright, was tasked with making headaches like the Whitewater scandal go away. Ickes described his role inside the Clinton White House as “director of the sanitation department.”

After Democrats got drubbed in the 1994 midterms, Ickes huddled with McAuliffe, then the Democratic National Committee’s finance chairman, and several other White House and DNC officials to hatch a plan to scare off any potential primary challengers to Clinton. A January 1995 fundraiser in Boston did just that, banking more than $1 million in one night. “[Clinton] blew the roof off the joint,” Ickes told me. “He was starting to get his stride back.”

The Boston bonanza previewed what was to come. Dick Morris, the longtime Clinton aide whom the president had brought in to plot his reelection effort, wanted to launch an advertising blitz beginning in the summer of 1995. No presidential campaign had ever run ads so early. Ickes backed the plan, but he flew into a rage after learning that Morris planned to pay for the ads with Clinton-Gore campaign money, which topped out at $45 million under the presidential public financing system. “My fucking ass you’re gonna use the campaign account,” he recalls telling Morris. “We’re gonna run out of money!”

So Ickes appealed to the Clinton-Gore campaign’s general counsel, Lyn Utrecht, who devised a novel solution: Drawing on an obscure Federal Election Commission opinion, she concluded that Democrats could craft their campaign spots as thinly veiled issue ads (that is, ones that never quite came out and said “vote for Bill Clinton”) and fund them with so-called soft money—unregulated, undisclosed, unlimited donations to the party from unions, corporations, and individuals that until then had only been used for general “party-building” operations. The Democrats went on to run so many issue ads paid for with soft money that they all but locked up the ’96 election by August.

It wasn’t long before Ickes and the DNC’s soft money strategy had exploded into a full-blown scandal over the White House coffee klatches, rides on Air Force One, and other perks used to ply Democratic donors. (The DNC would later return nearly $3 million in illegal donations, some from overseas sources.) Three days after Clinton’s victory, Ickes picked up the Wall Street Journal on the doorstep of his Georgetown home to find that he’d been fired for his role in the 1996 fundraising push. Congressional investigators probing the White House’s role in Clinton’s reelection effort, as well as other matters, would ultimately subpoena Ickes 34 times. He testified under oath 32 times, before six federal grand juries, and paid upward of $500,000 in legal fees. Such was the price of loyalty.

ONE EVENING SOON AFTER THE 2002 midterm elections, Ickes and a group of Democratic political honchos gathered at BeDuCi, a posh Mediterranean restaurant near his office. Seated around the table were EMILY’s List founder Ellen Malcolm, Service Employees International Union (SEIU) president Andy Stern, Stern’s adviser Gina Glantz, AFL-CIO political director Steve Rosenthal, Sierra Club director Carl Pope, Ickes, and Enright. The group discussed the upcoming election, and how best to marshal their manpower and money to defeat President George W. Bush. The newly enacted McCain-Feingold law had banned soft money, Ickes’ weapon of choice in 1996. The BeDuCi crowd drafted up a new strategy: They would train their firepower on a handful of battleground states, and they would raise money using an obscure type of tax-exempt organization, the 527 committee.

So goes the origin story of America Coming Together (ACT), one of the most sophisticated get-out-the-vote operations in the history of Democratic politics. Ickes also created another 527 dubbed the Media Fund to hammer Bush with TV and radio ads between the end of the Democratic primary fight and the Democratic convention, a vulnerable period for a presidential challenger. When it came to fundraising, the groups acted in unison; Ickes and Malcolm were the rainmakers. Ickes told me, “We traveled all over hell’s half acre…It was Ellen and I running around with our PowerPoint and our fucking tin cups.”

Their tin cups filled up fast. Ickes says he’d never heard of billionaire financier George Soros—until Soros pledged an initial $10 million to ACT. He didn’t know a thing about Progressive Insurance chairman Peter Lewis, who matched Soros’ $10 million. Then Andy Stern’s SEIU kicked in $32 million in manpower and cash. Republicans howled that Soros’ donation “had purchased the Democratic Party” and—in stark contrast to the deregulatory approach to campaign finance currently favored by many GOPers—urged the Federal Election Commission to outlaw 527s. “We were in pig heaven,” Ickes recalls. “We never had this kind of money to deal with.”

ACT and the Media Fund trounced the competition when it came to fundraising. All told, Democratic-leaning 527s outspent conservative ones by a 3-1 margin, $320 million to $109 million. ACT and the Media Fund together hauled in $202 million. Nearly half of that sum came from just five donors—Soros, Lewis, Hollywood producer Steve Bing, the SEIU, and the AFL-CIO. Democrats had never raised that much money for an independent effort, and never so much from such a small cadre of donors. (The Federal Election Commission later slapped ACT and the Media Fund with a combined $1.4 million in fines for illegal campaign spending.)

Democrats, of course, still failed to knock Bush out of office. But from the ashes of ACT emerged Catalist, a cutting-edge national voter database akin to the one Republicans had put in place more than a decade before. The final decision of ACT’s board was to create Catalist. Ickes agreed to raise the initial $5 million to make it a reality.

Then, on a bright, clear October day in 2005, a car swerved in front of Ickes as he guided his Vespa scooter down Pennsylvania Avenue. The collision threw him into the air before he came down on his right hip, shattering the socket. Without his helmet, Ickes says today, “I’d be six feet under.”

Ickes spent 16 days bedridden at George Washington University Hospital. One orthopedic surgeon said he might never walk again. As Ickes recovered, Enright set up a mobile office in his hospital room. He wanted to get back to work on Catalist: “There was money to be raised!”

NOT LONG AFTER LEAVING THE Obama White House in February 2011, Sean Sweeney paid a visit to his old friend Ickes. He wanted Ickes’ advice about raising big money. Seated around the wooden conference room table, the two men talked for an hour and a half as Ickes detailed the dance needed to woo the biggest donors in Democratic politics. Fundraising, he stressed, is no cakewalk: You build a list of carefully selected donors to court, research their giving histories and personal interests, pitch their advisers or “gatekeepers,” and travel all over the country asking for money. Presidential-level fundraising is nothing like how people imagine it, Ickes says; rarely do you meet donors like Franklin Haney who buy in right away.

Six weeks after their meeting, Sweeney asked Ickes to join Priorities’ board. “You might want to go back and check with your overlords, whoever they happen to be,” Ickes told him. The optics weren’t good: Ickes was a registered lobbyist who’d represented unions, public utilities, and trade groups. He also suspected that Obamaland blamed him for advising Hillary Clinton to stay in the 2008 race until Puerto Rico’s June primary. Ickes denies doing this, but he did scratch and claw to recruit superdelegates for Hillary well after her campaign had been written off; the bitter primary fight had left some lasting enmity between the Clinton and Obama camps. Two days later, Sweeney rang again. Now they wanted to make him Priorities’ president.

Ickes says his work with Priorities has been “sobering”—nothing like 1996 and 2004, when the money poured in. He, Sweeney, Burton, and others have crisscrossed the country, hitting up every major donor who’ll sit for their PowerPoint spiel. Priorities’ fundraising pace has gathered speed in recent months, snagging big donations like Haney’s $1 million and $2 million from Qualcomm cofounder Irwin Jacobs and his wife, Joan. (Burton also says Priorities has $20 million in commitments from donors.) Yet even with the uptick, Priorities will be hard-pressed to meet its $100 million target; in July, Ickes told me he’d revised that goal down to $75 million. That pales in comparison to the hundreds of millions Rove- and Koch-linked groups plan to spend.

Priorities and the other Democratic super-PACs have struggled for a number of reasons, say Ickes and other fundraisers. There’s the disgust with outside spending, which Obama himself helped fuel. In 2008, his campaign urged outside groups, like strategist Paul Begala’s Progressive Media USA PAC, to wind down so the campaign could better control its message. (Ironically, it was Burton who was tasked with conveying the directive.) Obama 2008’s message to donors was: If you want to support the campaign, donate to and bundle for the campaign itself. In 2010, the president called super-PACs a “threat to democracy.” But after realizing he’d be seriously outspent without outside help, Obama grudgingly blessed Priorities USA Action and dispatched top aides—including David Plouffe, who masterminded the 2008 win—to help pitch donors. Yet many big Obama backers have yet to pony up: By late July, just 15 of his 638 bundlers had given to the Obama super-PAC.

That has made Ickes’ job even harder. While the vast majority of major Clinton donors signed on with Obama for the 2008 general election, Ickes told me some are reluctant to fund Priorities when so few of Obama’s core backers are giving big. They take his long-standing supporters’ hesitance as a cue that either Obama isn’t really in trouble or the super-PAC isn’t a smart investment. “Why should we put money in if they’re not?” these donors tell Ickes.

Ickes faults the Democrats who anonymously suggested to reporters in 2010 that Obama, who beat all presidential fundraising records in 2008, could raise $1 billion for his reelection. Donors are wondering, “What do you need my paltry million for?” he says. “You fucking guys are gonna raise a billion!” He also suspects that some donors shy away from big-check super-PACs because they bought into the Obama campaign’s small-donor emphasis and are disenchanted with the post-Citizens United playing field.

Then there’s the lack of a nemesis: In 2004, donor anger ran so high, Ickes recalls, that an unknown Philadelphia financier had mailed ACT a million-dollar check—unsolicited. “We had the best fundraiser in 2004 that Democrats had stumbled across since Lyndon Johnson,” he says. “It was George W. Bush.”

Today a similar dynamic exists—only it’s Republicans relying on outrage at Obama to reel in millions. “You can walk into certain rooms and say, ‘We’ve got to get rid of Obama,’ and out come the big checks,” says Colby College’s Anthony Corrado.

Obama’s lukewarm rapport with donors hasn’t made Ickes’ job easier. Unlike Clinton, who mastered connecting with his supporters and stroking their egos, Obama tends to keep his backers at a remove. It shows up in the small things, says one wealthy Democrat’s adviser, like asking for $30,000-plus to attend a dinner and then making attendees pay for their picture with the president. “The White House has been too late in reaching out to their donors and making them feel appreciated,” this adviser told me. “You can’t go and ask for a million dollars from someone who can’t get a White House tour for his daughter.”

Yet all those factors still don’t fully explain the Democratic donor malaise. “You still sort of have to scratch your head and say, ‘This is the president of the United States, and he could lose,'” Ickes says. But he’s not giving up. “Hope springs eternal, and now Romney’s on a roll, he’s raising money, and the Republicans really think they can win the White House,” Ickes says. “Will things pick up? I think they will.”

Enough to reach Priorities’ $75 million goal? Enough to swat back the attacks headed Obama’s way this fall? Enough to land a few good punches on Romney?

Ickes closes his eyes and shrugs. “Who the hell knows?”