Protesters throw rocks at the US Embassy in Cairo, September 2012.Amanda Mustard/ZUMAPress

To hear Republicans explain it, the protests at US embassies around the world and the attack on a US consulate in Benghazi, Libya, that left four Americans dead are a result of the Obama administration “projecting weakness.”

“When we project weakness abroad, our enemies are more willing to test us, they are more brazen and our allies are less willing to trust us,” said vice presidential nominee Paul Ryan at an event in Colorado last week. “[T]hat will not happen under a Mitt Romney administration because we believe in peace through strength.” Ryan was referring to potential defense cuts, so if Al Qaeda pays enough attention to American budget politics to base its strikes on funding cuts then they probably know Ryan projected weakness by voting for them in the first place. Romney adviser Richard Williamson went so far as to suggest to the Washington Post last month that under a President Romney, no protesters would dare defile an American embassy. “In Egypt and Libya and Yemen, again demonstrations—the respect for America has gone down, there’s not a sense of American resolve and we can’t even protect sovereign American property,” he said.

As the details behind the Benghazi attack come to light, it’s becoming increasingly clear that the White House’s initial assessment of the attack as spontaneous rather than preplanned was inaccurate. But behind the comparisons to Jimmy Carter and the references to “peace through strength” is a dubious policy critique: not just that Obama is Carter and Romney is Reagan, but that somehow sufficient man-musk from an American president can dissuade any potential terrorist from laying his finger on an American diplomat.

It’s true that during Carter’s term, several major attacks occurred at US embassies. The most famous is the 1979 takeover of the US embassy in Tehran, but rumors that the United States was involved in the seizure of the Grand Mosque in Mecca, Saudi Arabia, led to attacks on embassies in Pakistan and Libya as well—in late November, after Reagan was elected president.

Wendy Chamberlin, a career foreign-service officer who was serving as the US Ambassador to Pakistan when Al Qaeda struck the World Trade Center on 9/11, says being a target is part of the job for diplomats serving in risky areas.

“High-profile targets like ambassadors have always been in danger because they’re the symbol of the United States,” Chamberlin says. “What you don’t want to represent is that you distrust the people, that you don’t want to engage with the people, that you hate being there. It’s an important part of your mission and get out and mix with the population.” Moreover, under the 1961 Vienna Convention on Diplomatic Relations it is actually the host country that is responsible for the security of diplomatic facilities, not the Marines. The primary responsibility of the Marine Corps’ Embassy Security Group states that its “primary mission” is “to prevent the compromise of classified material vital to the national security of the United States,” while their “secondary mission” is to “provide protection for US citizens and US government property” during “exigent circumstances.” Their first responsibility is to guard secrets, not diplomats.

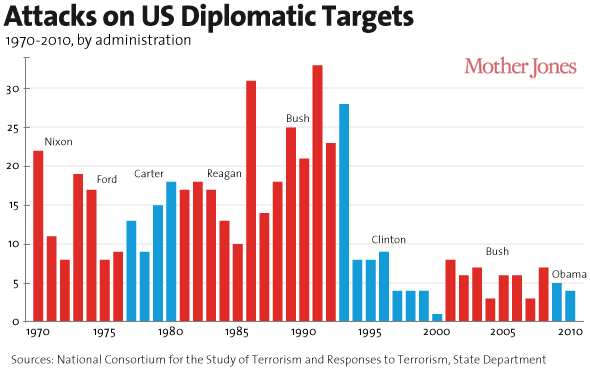

Having Ronald Reagan in office didn’t mean an end to attacks on US diplomatic targets. Despite Reagan’s refrain of “peace through strength,” several high-profile attacks on US diplomatic facilities occurred on his watch, including the bombing of the US embassy in Beirut, Lebanon, by Islamic militants. Twice. According to the Global Terrorism Database compiled by the University of Maryland National Consortium for the Study of Terrorism and Responses to Terrorism (START), attacks on American diplomatic targets actually rose during Reagan’s term—before beginning to subside in the mid-1990s.

“That follows the trend of terrorism generally,” says Erin Miller, a research assistant at START who manages the Global Terrorism Database. “In the early 1990s there’s a drop-off worldwide in terrorism against pretty much all target types.” Miller cites the collapse of the Soviet Union, and a subsequent wane in leftist terrorism as one possible explanation for the downturn beginning in the mid-1990s.

The decline is probably not because terrorists were intimidated by Bill Clinton more than they were by George H.W. Bush. Two of the worst terrorist attacks on American diplomatic targets, Al Qaeda’s bombing of US embassies in Kenya and Tanzania in 1998, happened on Clinton’s watch. It does however, make the Romney campaign’s claim that having a Republican in office will frighten terrorists out of striking at American diplomats or staging violent protests at American embassies extremely dubious. The UMd. database lists 64 attacks on American diplomatic targets during the George W. Bush administration, including car bombs at the US embassy in Yemen and armed attackers assaulting a US consulate in Saudi Arabia.

It’s currently unclear to what degree mismanagement, security lapses, or intelligence failures meant the United States failed to anticipate the attack on the consulate in Benghazi. But no matter which party is in office, no matter who is president, terrorism and violence are always going to be a potential risk for foreign-service officers serving in troubled areas. The important thing, Chamberlain says, is to stay engaged.

“Every ambassador and [foreign-service officer] understands the risks we take in being abroad,” Chamberlin says. “I don’t know any ambassador who hides in his embassy. Getting out with the public and speaking is our job, it’s why we’re there. If you don’t want to do that you shouldn’t go.”