Portraits

Project Credits

Kate Sheppard, reporter; Matt Eich, photographer; Ben Breedlove, Brett Brownell, Jaeah Lee, Tasneem Raja, producers. Thanks to NPR Apps for producing and open-sourcing In Memoriam, which made this project possible.

Jackson Women's Health Organization holds the dubious distinction of being Mississippi's only remaining abortion clinic. In 1981, there were 14, but thanks in part to increasingly repressive legislation, the others have closed.

Last April, Republican Gov. Phil Bryant signed a new law requiring any doctor performing abortions in the state to have permission to admit patients at a local hospital. That's a problem for Jackson Women's Health, since neither of its two doctors—both of whom fly into Mississippi to provide abortions—has admitting privileges. Bryant called the law "the first step in a movement, I believe, to do what we campaigned on...to try to end abortion in Mississippi."

Abortions in Mississippi are now only legal in clinics until 16 weeks of pregnancy—many other states permit the procedure up to 24 weeks. The state requires abortion clinics to abide by many of the same building codes as hospitals, even though other medical offices don't have to follow these rules. Doctors must perform a sonogram and offer the patient an opportunity to see the image and listen to the fetal heartbeat. All women must attend counseling with a doctor and then wait at least 24 hours before undergoing the procedure. Minors must have the consent of both of their parents. A few other states have passed some of these restrictions, but Mississippi has them all.

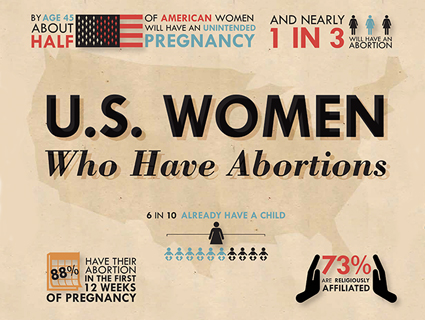

Mississippi already has one of the lowest abortion rates in the United States, with just 5 percent of women electing to end their pregnancies—compared to 19 percent nationally. It is one of just three states—along with North and South Dakota—that have only one clinic and zero providers who live in-state.

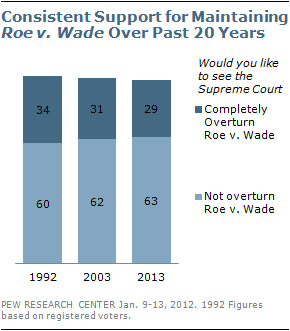

The Center for Reproductive Rights has challenged the new law, and the state department of health has given the clinic until January to comply. If it fails, Michelle Movahed, an attorney at the center, worries that the closure could set off a domino effect, with more and more legislatures using red tape to close clinics—in effect nullifying Roe v. Wade one state at a time. "Mississippi is the dream for what anti-abortion groups are trying to have happen."

Parker, 50, lives in Washington, DC, and flies to Jackson once a month. "Growing up in the South, I had a traditional religious upbringing," he says. "There were certainly lots of unwed pregnancies, but it was just sort of implied that if a woman became pregnant it was her obligation to continue the pregnancy."

But when he began practicing as an ob-gyn, Parker says, "I was faced with seeing women all the time who had unplanned pregnancies. So that started a 12-year path of wrestling with the morality of providing abortion care. [In the end,] I felt obligated ethically, morally, and spiritually. So I did."

In 2011, a colleague asked Parker if he'd be willing to travel to a clinic in Mississippi that had no local providers. "I had reservations. All I heard about it growing up was Mississippi Burning. But the majority of the women who were going to be affected by the closure of the clinic are black women. If I can't make those women a priority as a black person and as someone from that region of the country, then who else will? Given that nobody in Mississippi will, because they've been harassed or they've left the state, this is what we're left with."

"I'm not so much for abortion," says Keba, 30, who asked that we use only her first name. "I feel like if you could go with another measure, go another route. It's something that I will probably think about and allow to haunt me for years to come."

"Really just the timing is not a good thing. I have two 11-year-olds, nine months apart. I have a seven-month-old. You see the difference [between] two kids and three. My older two are having to go without. It's unfair to them. That's the reason I can't have another baby right now."

"I've been sick. I just got back to working after having the latest baby. I can't financially afford to just sit back and be caught up with this sickness for the next nine months, be out of work for six more weeks, doctors' appointments. I just can't afford not to come in. This is just the best decision for my household right now."

SHANNON BREWER-ANDERSON, Clinic Director

"I have six kids," says Brewer-Anderson. "I've been through not having any money, don't know how I'm going to pay the light bill, daddy's not there, don't know how I'm going to get another bag of Pampers. So I understand what these women are going through. I was one of those young, dumb girls. That's what I always tell people. I didn't know anything about abortion. We never spoke about abortion. I didn't know abortion clinics even existed here."

"Some people will come from two, three hours away. They don't even have a car. Somebody brought them. They paid someone to bring them here two different times. That shows you how desperate a woman would be to get this taken care of. She rode the Greyhound bus from wherever she came from, got a taxi here, then had to call a taxi to take her back."

"When you work here, it's not just like a job. The fact that this is the only clinic here in town, it's like you're part of something that is pretty big."

But she worries. Not long ago, state inspectors showed up for a surprise visit. "There is nothing that makes me more nervous than dealing with the department of health. The protesters can stand out there all day and do whatever they want to do and scream. There is nothing that can close it down except the department of health."

"I was found in a shoebox," says McMillan. "Abandoned at birth, naked, in the middle of the night in Alexandria, Louisiana." A young couple adopted him.

McMillan, 69, is known at the clinic as the guy who throws the plastic babies into your car window. He's clad in bright yellow rain pants not because of the weather, but because the owner of the house behind him turns the sprinkler on him each morning.

"I call myself a peacemaker. What did Jesus say in the Beatitudes? He said, 'Blessed are the peacemakers.' Who are we trying to make peace between? A mother and a child. The No. 1 instinct is that between a mother and child. If you don't believe me, go to the zoo."

Four years ago, McMillan, who says he has been arrested 69 times at abortion clinics, threatened one of the clinic's doctors. Since then, a court order has kept him 50 feet away from the clinic door. "I said, 'Your days are numbered, just like mine,'" McMillan says. "They said it was a threat. I said that was a religious liberty, a point of view I had." Still, some clinic staffers are worried about harassment from protesters; one of the clinic's doctors dons an alien mask each time he comes in.

"We're telling government this has got to end and we're willing to suffer to change it," McMillan says. "We're not going to shoot anybody."

"I was intended to be here," says Thompson, a 15-year veteran of the clinic known to all as Miss Betty. "I had a baby when I was 16. I could certainly relate to what was happening here."

"Most women who come in here, they have made up their mind," she says. "Those that are ambivalent, you can recognize them when they walk in the door."

"I don't think [women] understand the gravity of all the things that are thrown in their way. They're so absorbed with their own personal crisis, they don't care what the rule is. 'You tell me what I need to do so I can do it.' It doesn't dawn on them that they have the right to be here. They feel like they're sneaking. You don't have to feel that way. And I tell them that."

This article has been revised.