The really desperate come early. George Bishop, 61, a lanky, gray-haired cabinet builder in a tropical shirt, has a red, swollen nose from a boil caused by his third sinus infection in the past five months. Diana Rios, 54, cheerful despite the arthritis pain in her back and knees, holds on tight to her purse and to her seven-year-old granddaughter and translator, Sofia. Lindsay Oliver, 28, is here because of hypothyroidism, Sjögren’s syndrome (an autoimmune disorder), anemia, chronic hives—and no insurance.

By 4 p.m. on a rainy winter afternoon, they are part of a small crowd assembled on a grassy field behind a chain-link fence outside the Palmer Feed Store in Orlando, Florida. Across the street is the county medical building, where volunteer doctors affiliated with the nonprofit group Shepherd’s Hope see uninsured patients on weekday nights. The clinic doesn’t start until 6, but it’s a first-come, first-served operation, and demand is high.

At 4:30, a security guard opens the doors to let the patients in out of the drizzle. Dozens of them soon fill rows of metal chairs in the lobby. They are anxious and ailing, but also chatty as they munch on the cookies offered up by the volunteer clinic manager. Many have multiple medical issues going wholly or partly untreated. Rios is here for “private” problems as well as back pain, arthritis in her knees, and bursitis in her shoulder that forced her to quit working in September when she could no longer lift the trays she helped prepare for an airline food company. As Sofia translates, Rios explains that she has been in Florida for 16 years but has never had health insurance. She ended up in the emergency room recently after she fell on her arm and was so immobilized that she couldn’t brush her teeth.

The raven-haired Oliver lost her job as a bank teller supervisor in July, leaving her and her three-year-old son uninsured. After months of unsuccessful job hunting, she finally signed on as a housekeeper at a Disney hotel. She’s gone without some of her expensive medications since August and is hoping the clinic can help.

Oliver, Bishop, and Rios are among the nearly 4 million Floridians who lack health insurance—more than 1 in 5 in a state with the second-highest rate of uninsured in the country. Obamacare is supposed to help fix that through a combination of new federal subsidies for private insurance as well as a generous expansion of Medicaid, the government insurance program for the poor and disabled.

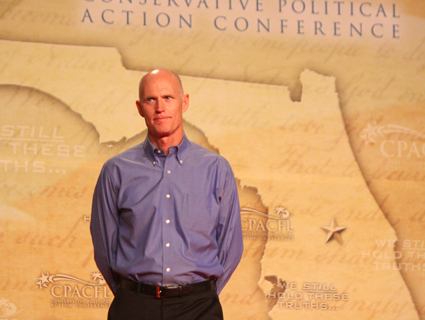

But the people at this clinic may not see many of these benefits, because Gov. Rick Scott and a tea-party-dominated state government have been at the forefront of the revolt against the law—and virtually every other form of government spending.

Even before he was elected in 2010, Scott spent $5 million of his own money—earned leading a health care company that derives much of its revenue from government payments—to fight Obamacare. Florida was the lead plaintiff in the Supreme Court case challenging Obamacare, and even after the court upheld the law, Scott refused to take steps to implement it. His fellow tea partiers are urging lawmakers to do the same: At a hearing in December, activist John Knapp told state legislators, “The American Constitution which you just swore an oath to uphold and defend has been contorted, hijacked, and reduced.”

Obamacare is a particular target of tea party wrath in Florida, but it’s hardly the only one in a state where the movement’s ideology has permeated every layer of government. In just one year, Scott and his conservative allies slashed state spending by $4 billion even as they cut corporate taxes. They’ve rejected billions in federal funds in one of the states hardest hit by the recession. They’ve axed everything from health care and public transportation initiatives to mosquito control and water supply programs. “Florida is where the rhetoric becomes the reality. It’s kind of the tea party on steroids,” says state Rep. Mark Pafford, a Democrat. “We’ve lost all navigation in terms of finding that middle ground.”

Similar shifts have occurred in other states where the tea party has amassed political power, including Michigan, New Jersey, Ohio, Texas, and Wisconsin. But no state has gone as far as Florida, where small-government advocates have seized the economic crisis and fiscal downturn to reshape the state, often sacrificing benefits for residents to make a broader political point.

Now, the Sunshine State may be a harbinger of another realignment: Support for Scott and the GOP is plummeting as Floridians see anti-government governance at work. But it may be too late for buyer’s remorse. After two years at the helm, the tea party’s legacy is likely to far outlast the movement.

WHEN HE RAN FOR governor as a political neophyte in 2010, Rick Scott’s main credential was his vast wealth, much of which he accumulated running Hospital Corporation of America. During Scott’s tenure, HCA was caught systematically defrauding federal health programs of millions of dollars through elaborate schemes to overbill the government for various services, including care it never provided. In 2000, the company pleaded guilty to 14 federal felony charges and paid $1.7 billion in fines in what was the largest government fraud settlement in history. A few months after the federal investigation was announced, Scott was forced to resign, but not before snagging a $310 million golden parachute.

Scott was not the choice of the state’s GOP establishment, but tea partiers loved him for his opposition to Obamacare and devotion to fiscal austerity, and he won the governorship by a single percentage point in 2010. Conservative Republicans also picked up seats in the Legislature, giving the GOP a supermajority at a time when Florida was facing a $3.6 billion budget shortfall.

Florida has never been known as a big-government state. An economy driven by tourism and real estate speculation has at times made it a haven for the less-than-scrupulous rich—Florida law helped O.J. Simpson shelter his assets in a mansion near Miami and avoid paying a civil judgment he owes Nicole Brown’s family. With no personal income tax, Florida collects some of the lowest taxes in the nation, leaving the government chronically starved for cash.

Even so, Scott rode into office with a promise to slash spending further. He unveiled his first budget in February 2011, at a private meeting with tea party activists, and publicly released it at a tea party rally.

The “jobs budget,” as Scott dubbed it, called for $4.6 billion in spending cuts, with education taking the biggest hit ($3 billion). It included a 17 percent cut to the agency that serves the disabled and proposed dropping virtually everyone but children and pregnant women from a state health program for the medically needy. The savings would be used to slash the corporate income tax from 5.5 to 3 percent, with the goal of eliminating it entirely by 2018. The budget also called for reducing property taxes by $1.4 billion, and cutting unemployment insurance taxes by $300 million, even though Florida’s unemployment trust fund was bankrupt. US News columnist Peter Roff dubbed Scott’s budget a “tea party dream” and speculated, somewhat prematurely, that it “almost assuredly gets him on the short list for vice president in 2012 or, depending on the outcome of that election, for president in 2016.”

Scott didn’t get everything he wanted, but the final budget approved by the Legislature was $4.6 billion smaller than it had been in 2006, even though the state’s population had grown by more than 700,000. And Scott vetoed a record $615 million worth of spending for, among other things: homeless veterans, meals for seniors, whooping-cough vaccines for low-income mothers, an independent living center for the developmentally disabled, and, of course, public radio.

The effects were felt almost immediately, from the state level—nearly 4,500 state jobs were eliminated—to local governments. In Broward County, the school system laid off 2,400 employees, mostly teachers. The Polk County school district sacked all of its college advisers, a move that prompted the wife of a tea party congressman, Rep. Dennis Ross (R-Fla.), to spearhead a fundraising effort to try to save them. (In the end, Cindy Ross, a member of a local high school’s booster club, wasn’t able to preserve the jobs, which had previously been protected by the 2009 stimulus—a measure her husband ran against.)

Florida already had a 10.6 percent unemployment rate and one of the stingiest unemployment benefits in the country—recipients max out at $275 a week. After Scott’s cuts, the percentage of unemployed people who received benefits fell from 17 to 15 percent—far below the national average of 27 percent. One reason: Florida now requires the jobless to take a 45-minute online math and reading test before even applying for benefits, a move the National Employment Law Project calls an “unnecessary burden” that may violate federal law. “Nowhere in the country is it this hard to get help when you lose a job,” said Valory Greenfield, a staff attorney at Florida Legal Services.

ON THE DAY I WENT to visit Abdel Rahman Gasser, a half-dozen elderly people, some attached to oxygen tanks and other medical equipment, were parked in wheelchairs outside Lakeshore Villas in Tampa, looking out across a parking lot and a small lake. Inside the lobby, a young girl plinked out Christmas carols on a piano while other kids sang to a group of residents, none of whom looked much younger than 80.

Abdel was also in a wheelchair, but when I met him in a conference room and asked his age, he smiled broadly and declared, “Sixteen years old!” Actually, Abdel is 17, but his brain no longer works the way it used to.

One rainy night in 2011, he and his brother were driving home from the beach when their car slid off the road and hit a concrete pole, which fell over and smashed the vehicle. Doctors eventually removed part of Abdel’s skull to relieve life-threatening swelling in his brain. He survived, but with the cognitive ability of an infant. He had to relearn how to breathe on his own and only recently began speaking in full sentences again. He can’t walk and has to be fed through a tube in his stomach. He gets confused about his name, though he recognizes his family and seems especially fond of his brother Tarik, who joked with him and held his hand while we visited.

Since June 2011, when he was released from Tampa General Hospital, Abdel has been here at Lakeshore Villas, a geriatric nursing home that also houses medically fragile children. He goes to a public high school for part of the week for a change of scenery and spends the rest of his time watching TV. Before his accident, Abdel, who was born in Egypt, was still becoming fluent in English. But his caretakers at Lakeshore don’t speak Arabic, making his isolation profound. (Nursing home administrators, who told me to leave when I came to visit with Abdel’s family, did not respond to a request to comment for this story.)

Abdel’s father, Gamal, is a compact, dignified man with gray-flecked hair who works as an engineer. He’d like to bring his son home. “Every time I walk in to see him, it’s like he’s doing nothing,” he says. “When he hears my voice or hears his brother’s voice, he’s like screaming and shouting. I’m sure it’d be much better if he comes to my house.” But Gamal, 58, and his wife cannot care for Abdel without help. They can’t lift the 160-pound teen, and they certainly can’t leave him home alone while they go to work.

The state would also like to send Abdel home. His caseworker from the Children’s Medical Services agency told Gamal, “As far as the state is concerned, your son is not sick.” But Gamal says the caseworker couldn’t give him any assurances that Abdel would get health services at home and, when Gamal pressed, merely offered to let Abdel stay at Lakeshore for three more months. “It’s like a car dealer throwing in a radio,” Gamal says with a rueful laugh.

Before Tarik had to wheel Abdel back past the fake painted submarine portholes that marked the entrance to the nursing home’s 15-bed children’s ward, I asked whether he liked living at Lakeshore Villas. Knitting his brows, he struggled for a minute to form the word, but then smiled and said, “No.”

Gamal is right to be concerned about getting home services for his son. Florida’s Medicaid program will pay for a nursing home bed for kids like Abdel, but not necessarily for home nursing services, even though they are often much cheaper than an institution. Seeking to control the cost of home care, the state contracted with a private company in February 2011 to review services for medically fragile children. Many of these kids are on ventilators and feeding tubes; they have hourly seizures and can die if their tracheostomy tubes aren’t suctioned every five minutes.

Yet parents suddenly found their private nursing hours slashed, the contractor arguing that the care was merely a convenience, not a medical necessity. “The parents are supposed to spend every second of their spare time with their kids” so as to eliminate the need for outside care, says Matthew Dietz, a lawyer who advocates for disabled kids. “I’ve had the state ask why the 16-year-old daughter can’t help. These are kids who need to be aspirated at night.”

Meanwhile, the state increased the reimbursement rates for kids in nursing homes and said parents were free to send their children there—even though the Miami Herald recently found that 130 children have died in geriatric nursing homes since 2006, a higher rate than among children cared for at home.

Between July 2011 and June 2012, the “utilization review” contractor reported saving the state nearly $45 million by cutting home health services. That’s one reason why Abdel is now part of a class-action lawsuit alleging that Florida has systematically discriminated against disabled children by refusing to provide them with needed services at home. Lawyers for the plaintiffs estimate that Abdel is one of about 250 kids, many of them foster children, who don’t belong in geriatric nursing homes but are stuck there, and that there are as many as 5,000 kids in Florida at high risk of ending up institutionalized because the state refuses to pay for home care.

The US Department of Justice has also taken notice. Threatening to sue, the Justice Department warned the state last September that it had “planned, structured, and administered a system of care that has led to the unnecessary segregation and isolation of children, often for many years, in nursing facilities.”

The DOJ said that by placing medically fragile kids, including infants, in nursing homes, Florida was depriving them of education, socialization, and stimulation they desperately needed. “They’re not given any toys or games in their room,” Dietz, who accompanied DOJ investigators on one of their visits to Florida nursing homes, told me. “All they do is watch TV day in and day out. It’s horrible. There’s no other word for it. It keeps me up at night.”

It didn’t have to be like this. In early 2011, the federal government awarded Florida a $37.5 million grant to help get patients out of nursing home care. The grant was part of a Bush-era program, but the latest round of funding ended up in a rider attached to Obamacare. And so, in June 2011, the state Legislature voted to reject the money.

Republicans said they were making a political point: “The legislature didn’t feel it was appropriate to take money from a bill that is unconstitutional,” then-state Rep. Mike Horner told the Orlando Sentinel. “It seemed that we were being inconsistent.”

The nursing home transition funding was just a portion of the millions in federal money that Florida has refused because it’s perceived as part of Obamacare. In 2011, Florida declined about $2 million for a Medicaid pilot project to give hospice care to very sick kids. It sought to prevent the Osceola County health department from accessing an $8.3 million federal grant to help expand two health clinics and build a new one and rejected $50 million worth of disease prevention funding. (The state did accept a $2.6 million abstinence-only sex ed grant provided through Obamacare.)

“Everything they thought was remotely connected to the Affordable Care Act was rejected,” says former state Senate Minority Leader Nan Rich, who is planning a run against Scott in 2014. “Somehow this governor had in his mind that if we reject the money, it reduces the deficit. Nothing could be further from the truth. It just goes to other states.”

Patti Nagel heads the Pinellas County Parents as Teachers Plus program, which uses home visits to prevent child abuse and premature births in an area that’s seen a dramatic increase in babies born addicted to prescription drugs. Obamacare provided a $31 million, five-year grant for programs like Nagel’s, but Florida sent back that money too. The program hung on for a few months until the Obama administration agreed to let local nonprofits apply for grants directly to the federal Department of Health and Human Services and circumvent hostile state governments. “We’ve lost a year of funding because of Scott’s shenanigans,” Nagel says testily. “I hope we’ll recover.”

But of all the big pots of federal money that Florida has rejected, none quite compares with Scott’s moves to block Obamacare’s expansion of Medicaid to the working poor. Today, a single parent with two children can’t qualify for Medicaid in Florida if she makes more than $3,200 a year—one of the nation’s lowest eligibility levels. Obamacare provides funding to raise that ceiling to $25,390 for a family of three. The federal government would pick up 100 percent of the cost of the expansion for the first three years, and 90 percent in later years—sending about $73 billion in new funding to the state in the next decade, with Florida’s share of the bill totaling just $9 billion. “At the most, the state would have to spend 10 cents for every dollar” it gets back, explains Laura Goodhue, the executive director of Florida Community Health Action Information Network, a nonprofit group that advocates for the uninsured. But Scott has said even that is too much.

If Florida rejects the Medicaid expansion, state hospitals stand to lose about $654 million a year in federal payments for care to the uninsured—payments that were reduced in Obamacare on the assumption that hospitals would gain revenue by caring for the newly insured. The hospitals, particularly public ones that have already lost $1.5 billion to state budget cuts over the past eight years, have been lobbying hard for the expansion, but tea partiers have been equally vocal, and in June, Scott announced that he would be rejecting the Medicaid expansion. “We don’t need to expand a big-government program to provide for everyone’s needs,” he said. “What we need is to shrink the cost of health care and expand opportunities for people to get a job so more people can afford it.”*

THE I-4 CORRIDOR BETWEEN Tampa and Orlando is one of the most congested highways in Florida, dominated by semis and the occasional billboard advertising emergency room wait times at local hospitals, most of which are owned by the governor’s former company, HCA.

The state has long proposed a high-speed rail line for the 84-mile stretch—the project, for which land had already been purchased and construction permits issued, was considered the most shovel-ready in the country when the US Department of Transportation awarded Florida $2.4 billion in stimulus funding in 2010. The state transportation department estimated that the rail line, envisioned as the first major segment of a high-speed corridor between Orlando and Miami, would have created nearly 50,000 new jobs at a time when the state’s unemployment rate was hovering around 12 percent.

Tea party groups, however, saw a Trojan horse for creeping socialism, and with the help of the conservative Reason and Heritage foundations, they set to work killing it. Conservative activists had already beaten back an unrelated Tampa-area ballot initiative that would have raised a penny-per-dollar sales tax for light rail, saying it was laying the groundwork for Agenda 21, a United Nations sustainable-development plan that they believed would “transfer American sovereignty to various tentacles” of the UN.

Tea partiers lobbied Scott to reject the Tampa-Orlando high-speed rail line on much the same grounds, and the governor obliged, arguing that the jobs it would create were “short-term” and the state would be on the hook for much more spending down the road. (Private companies had promised to pick up the tab for any cost overruns or operating losses—and the Tampa Tribune discovered that Scott’s own transportation department had projected that the train would turn a profit.) Scott sent $2.4 billion back to Washington, a decision that one of Florida’s Republican members of Congress, John Mica, said “defies logic.” The Obama administration turned around and gave $1 billion of the money to California.

Over the past three years, Florida tea partiers, often invoking Agenda 21, have also fought bike lanes, regulations to save endangered manatees, climate change initiatives, and pretty much anything that would protect the state’s environment. Scott himself, while on the campaign trail in 2010, joined in a protest against the South Florida Water Management District, which is charged with protecting the area’s water supply, combating flooding, and restoring the Everglades. The protest targeted a deal negotiated by then-Republican Gov. Charlie Crist to buy 187,000 acres of farmland owned by United States Sugar Corp. to use for Everglades restoration. The $1.75 billion deal was derailed by dwindling state revenues, but the water district went ahead and purchased about 27,000 acres of the sugar land for $197 million.

The water district still has the option of buying the rest, but once Scott took office he made sure that wouldn’t happen. He stacked the district board with new appointees, including one of the protest organizers and the former operator of a garbage incinerator that has been a leading source of mercury pollution in the Everglades. Then, Scott pushed a bill that whacked $128 million out of the district’s budget, prompting the layoffs of 134 workers. Those laid off included scientists with decades of expertise on the Everglades—just at a time when climate models show that sea level rise will soon threaten some of Florida’s drinking water supplies, making Everglades restoration critical. “We have to get this done or we’re going to have a complete disaster,” says Jonathan Ullman, the Everglades organizer at the South Florida chapter of the Sierra Club.

In Scott’s first year, the number of environmental enforcement actions in the state fell nearly 30 percent, as did the pollution penalties, and the Department of Environmental Protection laid off key staff. The agency “was pretty close to bare bones at the beginning of Scott’s tenure,” says Jerry Phillips, the Florida director of Public Employees for Environmental Responsibility, who used to work in the agency. “Now you’re cutting into bone.”

Tea partiers have also risen up to oppose the tyranny of septic-tank inspections. In 2011, activists persuaded the Legislature to overturn a 2010 law that required old and potentially leaky septic systems to get inspected every five years to prevent human waste from seeping into the water supply. “They don’t realize the damage done when you remove revenue from the budget,” says Pafford, the Democratic legislator from Palm Beach, whose district has seen record flooding in the past year. “We defecate in the water we drink because we don’t want government control. At the same time we offer 18 bills on whether a woman can have an abortion. There are a lot of people who miss Gov. [Jeb] Bush—that’s where we are.”

It used to be that a few government expenditures were immune from partisan disagreement—cops, potholes, mosquito control. But not anymore. Most of Florida’s mosquito abatement work is done at the local level, where independent taxing districts are responsible for the bulk of the eradication efforts. These districts have become targets of tea party wrath. Last year, a trio of conservative activists dubbing themselves the “Mosquitoteers” challenged several members on the Anastasia Mosquito Control Board in St. Augustine. They campaigned on a plan to cut mosquito control taxes and the district’s budget and bought a billboard reading: “Smash mosquitoes and the friends of Obama.” Never mind, notes board member Vivian Browning, that the seats are nonpartisan: “Mosquitoes, they don’t care if you’re Republican, Democrat, or independent. They can eat you, infect you, kill you, regardless of party.” One of the Mosquitoteers, a reserve sheriff’s deputy, defeated a University of Florida biology professor who is an expert in mosquito-borne diseases—a concern in a state that has regular outbreaks of West Nile virus and has seen an uptick in dengue fever.

The state Legislature has also done its part to liberate mosquitoes from the shackles of big government. In 2011, the Republican-dominated Legislature slashed the state’s contribution to mosquito control by 40 percent. Florida A&M University closed one of two major mosquito research labs in the state after the Legislature axed $500,000 in research funds. Public health officials succeeded in restoring money to keep the lab open, only to see Scott kill it with a stroke of his veto pen. Along with other budget cuts, the closure halved the number of Florida scientists working on mosquito control.

“There’s maybe a perfect storm of sorts,” says Joseph Conlon, a technical adviser to the American Mosquito Control Association in Florida. “You’ve got the government rightfully trying to cut budgets across the board, but down here in Florida, the place would be uninhabitable without mosquito control.”

For all of his tax cutting and Obamacare bashing, Rick Scott did not end up on the vice presidential short list. Nor is he considered a presidential contender in 2016. Instead he has become so unpopular that Mitt Romney’s campaign largely steered clear of him in a critical swing state; just after his first budget, his approval rating dropped to 29 percent, the lowest of any governor in the nation. This past November, the GOP lost its supermajority in the Florida Legislature, and voters ditched tea party icon Rep. Allen West. “The oxygen of the tea party is escaping,” says Christian Ulvert, a Democratic political consultant in Miami.

Not coincidentally, Scott has softened a bit, reversing course on some of his most radical budget cuts and restoring $1 billion in education funding. He is even negotiating with the Obama administration over the Medicaid expansion (but only, apparently, in an effort to turn the whole program over to private managed-care plans). He remains under fire for myriad other decisions—from shuttering a state hospital in the midst of the nation’s largest tuberculosis outbreak to cutting funding for rape crisis centers during Sexual Assault Awareness Month. Polls have been showing Scott losing handily to a generic Democrat—and more than half of the state’s Republicans would like to see him face a primary challenge in 2014, according to a Quinnipiac University poll in December.

But even if Scott ends up a one-term governor, his legacy won’t easily be reversed. When he rejected the high-speed rail money, the state passed up an opportunity to upgrade its underfunded transit system that it may not soon see again. Florida’s internationally renowned mosquito control system took a half century to build, but only three years to decimate. Likewise with public health, says Nan Rich, who fought the cuts in the state Senate: “The infrastructure is being destroyed and responding to public health crises becomes more difficult,” she says. “I shudder to think if what happened with Hurricane Sandy had happened here.”

The tea party’s influence may be waning, but that might not matter in the end. “I don’t think it’s insurmountable to recover from dismantling 50 years’ worth of great government structures that made society in Florida better,” says Rep. Pafford. “But it could be a decade before we really begin to address some of these issues. It’s gonna take dollars.” Pafford thinks the biggest task ahead is “rebuilding the confidence of the average Floridian that an elected person like the governor can actually do good things.” What’s happened here, he says, “is really an incredible example of how government should not work. Hopefully people can learn from Florida’s tea party experiment.”

UPDATE, Thursday, February 21: On Wednesday, Scott announced that he had changed his mind about the Medicaid expansion and would support extending Medicaid to people up to 138 percent of the poverty line for three years, after which the program would have to be reevaluated. The state Legislature, however, still has to approve such a move, and it’s unclear whether there is enough support for it among the GOP majority, despite Scott’s change of heart.