This story was produced in partnership with Tumblr Storyboard.

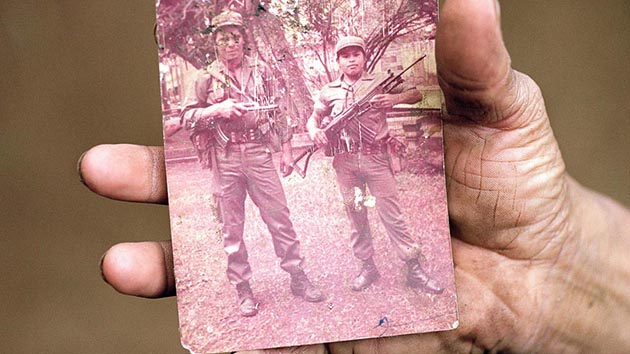

It began with a trip back home, to a small town in the country’s western valley, to visit his dying grandmother. More than a decade after El Salvador’s bloody civil war had ended, Juan Carlos, a 38-year-old photojournalist, wanted to see how life had changed. Was his country, one of the most violent in the Western Hemisphere, better off after 12 years of war? Sure, there were shiny new roads and malls, but was the country any safer?

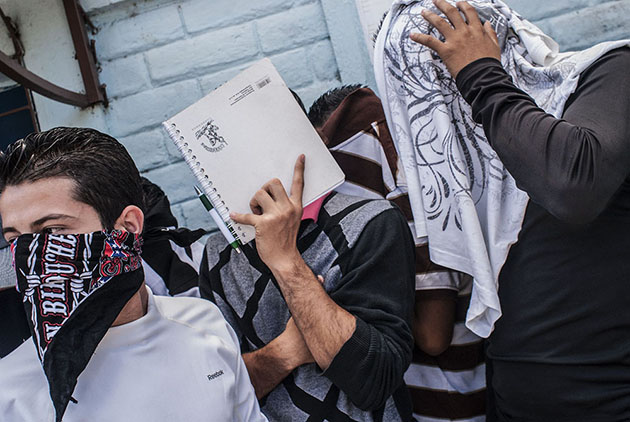

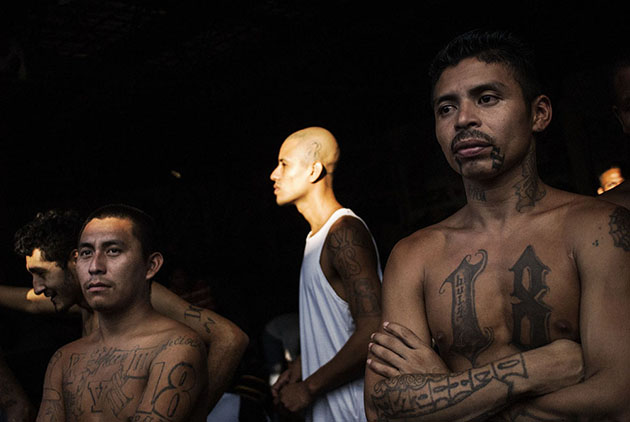

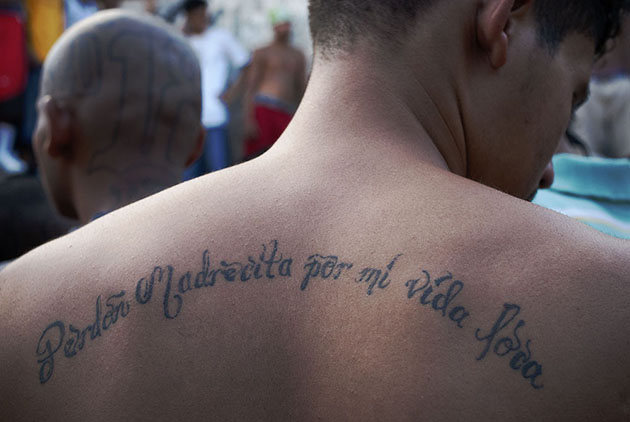

Juan Carlos began by documenting infrastructure and families, education and health systems, traveling for long stretches between El Salvador, where he was born, and San Francisco, where he now lives. But it didn’t take long for a new focus to emerge: the gang culture, and accompanying terror, that had seeped into the fabric of everyday Salvadoran life. With an estimated 64,000 identified gang members, El Salvador’s street gangs—or maras, as they’re known to locals—operate like armies. They control neighborhoods, and can stop buses from running. They hold press conferences. They are incestuously intertwined with the police. In other words, they call the shots—as well as fire them. At its peak, in 2009, the gangs were responsible for a homicide rate that reached 14 deaths per day.

Last March, however, the country’s two most violent gangs—Mara Salvatrucha (MS-13) and Barrio 18—suddenly declared a truce. In exchange for better prison conditions—and the transfer of gang leaders to a less-restrictive facility—the two armies agreed to halt the violence. Since then, El Salvador’s official homicide rate has plummeted by more than 60 percent; in April, the country of 6 million saw its first day without a single murder in years. “This is an opening,” a former gang member said at the time, “part of a peace process that we have been pushing for years.”

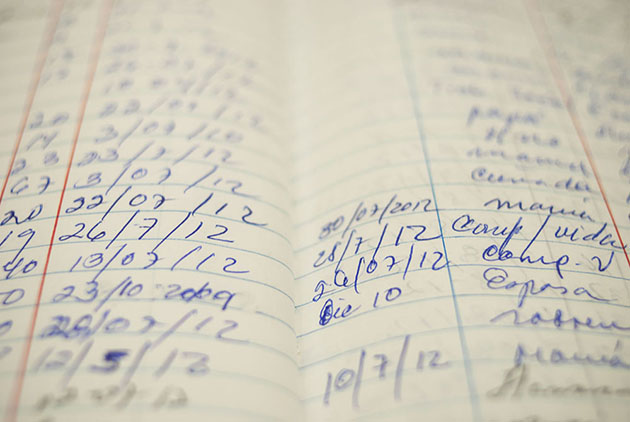

And yet, one year into the truce, the reality of life in El Salvador isn’t quite so simple. Sure, the killings have abated, but extortion, theft, and drugs remain rampant. Reports of missing persons have skyrocketed since the truce began, and mass graves have cropped up all over the countryside. On Tuesday, a prominent social worker, a former gang member who had helped broker the truce, was shot point blank in front of the social-service center where he worked. For locals who’ve grown used to gang warfare as part of daily life, the reality is clear. “We leave our home and don’t know if we are going to come back,” as one put it.

In partnership with Mother Jones, Tumblr commissioned a series of portraits from Juan Carlos to show what life is like in his home country. The images offer a comprehensive view of life in El Salvador after the truce, from inside overcrowded prisons to the plight of residents haunted by memories disappeared. Tumblr’s Jessica Bennett spoke with the photographer about the project—called Truce In and Out—as well his newly launched blog and website.

Jessica Bennett: You’ve documented the war in Iraq, the earthquake in Haiti, and New Orleans post-Katrina. Why go back to your home?

Juan Carlos: In my opinion, photography is a responsibility. There are so many stories here that aren’t told by mainstream media: gangs, violence, an area contaminated by lead by a factory that manufactured car batteries. I wanted to document my country and see what postwar El Salvador was about. Were we better off? What did the war accomplish? Did we become a better country?

JB: I take it the gangs were impossible to ignore in that equation.

JC: It got to a point where it was just everywhere, all around you. So I decided to take a deeper step into documenting the violence. I’m from a small town in the western part of El Salvador, and in 2008, there were about eight killings in a single day—just in that town. In other places, when photographers document crime, they go on patrols with ambulances or police. But I would just walk down the street. I walked into a crime scene where a kid had just been shot in the head, right outside a bakery where I was buying bread. Another time, a cousin told me, “Hey, a guy just got shot in the park.” I went, and there was a bench full of blood. This kind of thing was happening all the time. I would be walking down the street and just: boom.

JB: You were a child during the first years of El Salvador’s civil war. Is the experience of gang life similar?

JC: You know, I was a small child during the war, but you’d wake up to the sound of gunshots. And the bodies. You’d wake up and there would be bodies on the road or the street—somebody killed the night before. It’s the same thing here: You still find bodies on the side of the road, mass graves, and disappeared. History is repeating itself—but for very different reasons.

JB: What’s it like being around all that death?

JC: It’s troubling, because you are always in that mode that something could happen to you. And sadly enough, that’s how Salvadorans would wake up, thinking “I could die today,” just like saying, “I’ve got to brush my teeth.” Psychologically, it’s stressful. Because normal things like taking a walk in a park become difficult. The violence is all around you. Salvadorans will tell you, that’s always in their mind. They never know what’s going to happen. That’s the thing—this isn’t just physical violence, this is psychological violence. It’s this feeling that something is going to happen to you, or that you can’t defend yourself, because you’re going to end up dead.

JB: What about the police?

JC: It became popular—gang members even write it on the wall—the saying: “See, Hear, Shut Up.” The culture has become that people don’t speak up, because they feel there’s no protection. You can’t even call the police, because there are informants in the police department. So there’s no trust. There’s nobody to turn to.

JB: But has the truce helped?

JC: The numbers have dropped. But in my opinion, a society that still has five or six murders per day is not a healthy society. Now you find more bodies on the side of the road in plastic bags; you find people just disappeared, or in mass graves. So what’s happening—or, at least, what many people believe is happening—is that the government is manipulating the numbers. They just found two girls who’d been missing since October, chopped into pieces. Yeah, we have fewer murders. But you still have extortion, and gang leaders—every time they have a press conference—can’t give a straight answer about when they’re going to stop. The crime may be down, but the fear is still there.

JB: It’s crazy to hear you say that gangs hold press conferences. For people who don’t know, how much power do gangs have?

JC: They have more power than the authorities. If you want to have a business, you pay them. They infiltrate the police: Gang members become policemen, and policemen become gang members. They have the power to stop people from doing the simplest things—like going to work—to make demands on the government. Pretty much they’re in charge.

JB: What do you think it would take solve the problem?

JC: People say, you know, just burn down the prisons—because that’s where all the gang leaders are housed. But that is not the answer. It’s more complicated. We’ve got to educate both sides. We’ve got to focus on prevention. The problem will never just go away. It’s like saying, “Let’s get rid of gangs in LA.” We’re not going to do that. But we can bring the numbers down. We can focus on prevention, and outreach to the new generations. Because all these young generations are growing up with all this violence, and what’s going to happen? Boom, they’re going to fall into that. That happens in any place where this is a problem, and it’s no different here.