<a href="http://www.shutterstock.com/cat.mhtml?lang=en&search_source=search_form&search_tracking_id=B568F3AC-9261-11E2-861A-4BBFACE6966E&version=llv1&anyorall=all&safesearch=1&searchterm=battered+woman&search_group=&orient=&search_cat=&searchtermx=&photographer_name=&people_gender=&people_age=&people_ethnicity=&people_number=&commercial_ok=&color=&show_color_wheel=1#id=67756033&src=F2D5AAAA-9261-11E2-8F99-E6F69DA4A24C-1-16">Warren Goldswain</a>/Shutterstock

This story first appeared on the TomDispatch website.

Picture this. A man, armored in tattoos, bursts into a living room not his own. He confronts an enemy. He barks orders. He throws that enemy into a chair. Then against a wall. He plants himself in the middle of the room, feet widespread, fists clenched, muscles straining, face contorted in a scream of rage. The tendons in his neck are taut with the intensity of his terrifying performance. He chases the enemy to the next room, stopping escape with a quick grab and thrust and body block that pins the enemy, bent back, against a counter. He shouts more orders: his enemy can go with him to the basement for a “private talk,” or be beaten to a pulp right here. Then he wraps his fingers around the neck of his enemy and begins to choke her.

No, that invader isn’t an American soldier leading a night raid on an Afghan village, nor is the enemy an anonymous Afghan householder. This combat warrior is just a guy in Ohio named Shane. He’s doing what so many men find exhilarating: disciplining his girlfriend with a heavy dose of the violence we render harmless by calling it “domestic.”

It’s easy to figure out from a few basic facts that Shane is a skilled predator. Why else does a 31-year-old man lavish attention on a pretty 19-year-old with two children (ages four and two, the latter an equally pretty and potentially targeted little female)? And what more vulnerable girlfriend could he find than this one, named Maggie: a neglected young woman, still a teenager, who for two years had been raising her kids on her own while her husband fought a war in Afghanistan? That war had broken the family apart, leaving Maggie with no financial support and more alone than ever.

But the way Shane assaulted Maggie, he might just as well have been a night-raiding soldier terrorizing an Afghan civilian family in pursuit of some dangerous Talib, real or imagined. For all we know, Maggie’s estranged husband/soldier might have acted in the same way in some Afghan living room and not only been paid but also honored for it. The basic behavior is quite alike: an overwhelming display of superior force. The tactics: shock and awe. The goal: to control the behavior, the very life, of the designated target. The mind set: a sense of entitlement when it comes to determining the fate of a subhuman creature. The dark side: the fear and brutal rage of a scared loser who inflicts his miserable self on others.

As for that designated enemy, just as American exceptionalism asserts the superiority of the United States over all other countries and cultures on Earth, and even over the laws that govern international relations, misogyny—which seems to inform so much in the United States these days, from military boot camp to the Oscars to full frontal political assaults on a woman’s right to control her own body—assures even the most pathetic guys like Shane of their innate superiority over some “thing” usually addressed with multiple obscenities.

Since 9/11, the further militarization of our already militarized culture has reached new levels. Official America, as embodied in our political system and national security state, now seems to be thoroughly masculine, paranoid, quarrelsome, secretive, greedy, aggressive, and violent. Readers familiar with “domestic violence” will recognize those traits as equally descriptive of the average American wife beater: scared but angry and aggressive, and feeling absolutely entitled to control something, whether it’s just a woman, or a small wretched country like Afghanistan.

Connecting the Dots

It was John Stuart Mill, writing in the nineteenth century, who connected the dots between “domestic” and international violence. But he didn’t use our absurdly gender-neutral, pale gray term “domestic violence.” He called it “wife torture” or “atrocity,” and he recognized that torture and atrocity are much the same, no matter where they take place—whether today in Guantanamo Bay, Cuba, Wardak Province, Afghanistan, or a bedroom or basement in Ohio. Arguing in 1869 against the subjection of women, Mill wrote that the Englishman’s habit of household tyranny and “wife torture” established the pattern and practice for his foreign policy. The tyrant at home becomes the tyrant at war. Home is the training ground for the big games played overseas.

Mill believed that, in early times, strong men had used force to enslave women and the majority of their fellow men. By the nineteenth century, however, the “law of the strongest” seemed to him to have been “abandoned”—in England at least—”as the regulating principle of the world’s affairs.” Slavery had been renounced. Only in the household did it continue to be practiced, though wives were no longer openly enslaved but merely “subjected” to their husbands. This subjection, Mill said, was the last vestige of the archaic “law of the strongest,” and must inevitably fade away as reasonable men recognized its barbarity and injustice. Of his own time, he wrote that “nobody professes” the law of the strongest, and “as regards most of the relations between human beings, nobody is permitted to practice it.”

Well, even a feminist may not be right about everything. Times often change for the worse, and rarely has the law of the strongest been more popular than it is in the United States today. Routinely now we hear congressmen declare that the US is the greatest nation in the world because it is the greatest military power in history, just as presidents now regularly insist that the US military is “the finest fighting force in the history of the world.” Never mind that it rarely wins a war. Few here question that primitive standard—the law of the strongest—as the measure of this America’s dwindling “civilization.”

The War Against Women

Mill, however, was right about the larger point: that tyranny at home is the model for tyranny abroad. What he perhaps didn’t see was the perfect reciprocity of the relationship that perpetuates the law of the strongest both in the home and far away.

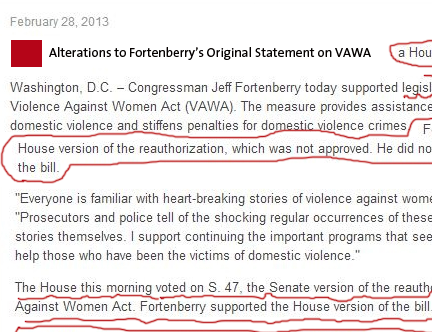

When tyranny and violence are practiced on a grand scale in foreign lands, the practice also intensifies at home. As American militarism went into overdrive after 9/11, it validated violence against women here, where Republicans held up reauthorization of the Violence Against Women Act (first passed in 1994), and celebrities who publicly assaulted their girlfriends faced no consequences other than a deluge of sympathetic girl-fan tweets.

America’s invasions abroad also validated violence within the US military itself. An estimated 19,000 women soldiers were sexually assaulted in 2011; and an unknown number have been murdered by fellow soldiers who were, in many cases, their husbands or boyfriends. A great deal of violence against women in the military, from rape to murder, has been documented, only to be casually covered up by the chain of command.

America’s invasions abroad also validated violence within the US military itself. An estimated 19,000 women soldiers were sexually assaulted in 2011; and an unknown number have been murdered by fellow soldiers who were, in many cases, their husbands or boyfriends. A great deal of violence against women in the military, from rape to murder, has been documented, only to be casually covered up by the chain of command.

Violence against civilian women here at home, on the other hand, may not be reported or tallied at all, so the full extent of it escapes notice. Men prefer to maintain the historical fiction that violence in the home is a private matter, properly and legally concealed behind a “curtain.” In this way is male impunity and tyranny maintained.

Women cling to a fiction of our own: that we are much more “equal” than we are. Instead of confronting male violence, we still prefer to lay the blame for it on individual women and girls who fall victim to it—as if they had volunteered. But then, how to explain the dissonant fact that at least one of every three female American soldiers is sexually assaulted by a male “superior”? Surely that’s not what American women had in mind when they signed up for the Marines or for Air Force flight training. In fact, lots of teenage girls volunteer for the military precisely to escape violence and sexual abuse in their childhood homes or streets.

Don’t get me wrong, military men are neither alone nor out of the ordinary in terrorizing women. The broader American war against women has intensified on many fronts here at home, right along with our wars abroad. Those foreign wars have killed uncounted thousands of civilians, many of them women and children, which could make the private battles of domestic warriors like Shane here in the US seem puny by comparison. But it would be a mistake to underestimate the firepower of the Shanes of our American world. The statistics tell us that a legal handgun has been the most popular means of dispatching a wife, but when it comes to girlfriends, guys really get off on beating them to death.

Some 3,073 people were killed in the terrorist attacks on the United States on 9/11. Between that day and June 6, 2012, 6,488 US soldiers were killed in combat in Iraq and Afghanistan, bringing the death toll for America’s war on terror at home and abroad to 9,561. During the same period, 11,766 women were murdered in the United States by their husbands or boyfriends, both military and civilian. The greater number of women killed here at home is a measure of the scope and the furious intensity of the war against women, a war that threatens to continue long after the misconceived war on terror is history.

Getting the Picture

Think about Shane, standing there in a nondescript living room in Ohio screaming his head off like a little child who wants what he wants when he wants it. Reportedly, he was trying to be a good guy and make a career as a singer in a Christian rock band. But like the combat soldier in a foreign war who is modeled after him, he uses violence to hold his life together and accomplish his mission.

We know about Shane only because there happened to be a photographer on the scene. Sara Naomi Lewkowicz had chosen to document the story of Shane and his girlfriend Maggie out of sympathy for his situation as an ex-con, recently released from prison yet not free of the stigma attached to a man who had done time. Then, one night, there he was in the living room throwing Maggie around, and Lewkowicz did what any good combat photographer would do as a witness to history: she kept shooting. That action alone was a kind of intervention and may have saved Maggie’s life.

In the midst of the violence, Lewkowicz also dared to snatch from Shane’s pocket her own cell phone, which he had borrowed earlier. It’s unclear whether she passed the phone to someone else or made the 911 call herself. The police arrested Shane, and a smart policewoman told Maggie: “You know, he’s not going to stop. They never stop. They usually stop when they kill you.”

Maggie did the right thing. She gave the police a statement. Shane is back in prison. And Lewkowicz’s remarkable photographs were posted online on February 27th at Time magazine’s website feature Lightbox under the heading “Photographer As Witness: A Portrait of Domestic Violence.”

The photos are remarkable because the photographer is very good and the subject of her attention is so rarely caught on camera. Unlike warfare covered in Iraq and Afghanistan by embedded combat photographers, wife torture takes place mostly behind closed doors, unannounced and unrecorded. The first photographs of wife torture to appear in the US were Donna Ferrato’s now iconic images of violence against women at home.

Like Lewkowicz, Ferrato came upon wife torture by chance; she was documenting a marriage in 1980 when the happy husband chose to beat up his wife. Yet so reluctant were photo editors to pull aside the curtain of domestic privacy that even after Ferrato became a Life photographer in 1984, pursuing the same subject, nobody, including Life, wanted to publish the shocking images she produced.

In 1986, six years after she witnessed that first assault, some of her photographs of violence against women in the home were published in the Philadelphia Inquirer, and brought her the 1987 Robert F. Kennedy journalism award “for outstanding coverage of the problems of the disadvantaged.” In 1991, Aperture, the publisher of distinguished photography books, brought out Ferrato’s eye-opening body of work as Living with the Enemy (for which I wrote an introduction). Since then, the photos have been widely reproduced. Time used a Ferrato image on its cover in 1994, when the murder of Nicole Brown Simpson briefly drew attention to what the magazine called “the epidemic of domestic abuse” and Lightbox featured a small retrospective of her domestic violence work on June 27, 2012.

Ferrato herself started a foundation, offering her work to women’s groups across the country to exhibit at fundraisers for local shelters and services. Those photo exhibitions also helped raise consciousness across America and certainly contributed to smarter, less misogynistic police procedures of the kind that put Shane back in jail.

Ferrato’s photos were incontrovertible evidence of the violence in our homes, rarely acknowledged and never before so plainly seen. Yet until February 27th, when with Ferrato’s help, Sara Naomi Lewkowicz’s photos were posted on Lightbox only two months after they were taken, Ferrato’s photos were all we had. We needed more. So there was every reason for Lewkowicz’s work to be greeted with acclaim by photographers and women everywhere.

Instead, in more than 1,700 comments posted at Lightbox, photographer Lewkowicz was mainly castigated for things like not dropping her camera and taking care to get Maggie’s distraught two-year-old daughter out of the room or singlehandedly stopping the assault. (Need it be said that stopping combat is not the job of combat photographers?)

Maggie, the victim of this felonious assault, was also mercilessly denounced: for going out with Shane in the first place, for failing to foresee his violence, for “cheating” on her already estranged husband fighting in Afghanistan, and inexplicably for being a “perpetrator.” Reviewing the commentary for the Columbia Journalism Review, Jina Moore concluded, “[T]here’s one thing all the critics seem to agree on: The only adult in the house not responsible for the violence is the man committing it.”

They Only Stop When They Kill You

Viewers of these photographs—photos that accurately reflect the daily violence so many women face—seem to find it easy to ignore, or even praise, the raging man behind it all. So, too, do so many find it convenient to ignore the violence that America’s warriors abroad inflict under orders on a mass scale upon women and children in war zones.

The US invasion and occupation of Iraq had the effect of displacing millions from their homes within the country or driving them into exile in foreign lands. Rates of rape and atrocity were staggering, as I learned firsthand when in 2008-2009 I spent time in Syria, Jordan, and Lebanon talking with Iraqi refugees. In addition, those women who remain in Iraq now live under the rule of conservative Islamists, heavily influenced by Iran. Under the former secular regime, Iraqi women were considered the most advanced in the Arab world; today, they say they have been set back a century.

In Afghanistan, too, while Americans take credit for putting women back in the workplace and girls in school, untold thousands of women and children have been displaced internally, many to makeshift camps on the outskirts of Kabul where 17 children froze to death last January. The U.N. reported 2,754 civilian deaths and 4,805 civilian injuries as a result of the war in 2012, the majority of them women and children. In a country without a state capable of counting bodies, these are undoubtedly significant undercounts. A U.N. official said, “It is the tragic reality that most Afghan women and girls were killed or injured while engaging in their everyday activities.” Thousands of women in Afghan cities have been forced into survival sex, as were Iraqi women who fled as refugees to Beirut and particularly Damascus.

That’s what male violence is meant to do to women. The enemy. War itself is a kind of screaming tattooed man, standing in the middle of a room—or another country—asserting the law of the strongest. It’s like a reset button on history that almost invariably ensures women will find themselves subjected to men in ever more terrible ways. It’s one more thing that, to a certain kind of man, makes going to war, like good old-fashioned wife torture, so exciting and so much fun.

Ann Jones, historian, journalist, photographer, and TomDispatch regular, chronicled violence against women in the US in several books, including the feminist classic Women Who Kill (1980) and Next Time, She’ll Be Dead (2000), before going to Afghanistan in 2002 to work with women. She is the author of Kabul in Winter (2006) and War Is Not Over When It’s Over (2010). To stay on top of important articles like these, sign up to receive the latest updates from TomDispatch.com here.